Fakes, Finds, and the Story of Clementine Hunter

This article is republished here courtesy of the *ANTIQUES ROADSHOW Insider* magazine, where it originally ran in the March 2014 issue.

Feb 24, 2014

ANTIQUES ROADSHOW host Mark L. Walberg was heading for the mobile unit (our traveling TV production truck) last summer when he caught my eye. He answered my question — "Where are you headed?" — before I could ask it: "Wes [Cowan] is appraising Clementine Hunter paintings!" he exclaimed.

Will there be a happy ending for two Clementine Hunter paintings uncovered in Baton Rouge? ROADSHOW's segment producer has the answer

This was not unexpected. ANTIQUES ROADSHOW was taping in Baton Rouge that day and Clementine Hunter was a well-known and prolific Louisiana folk artist. The show's paintings and folk art experts expected to see at least a few examples of her work that day.

As Walberg bounded into the truck, hoping to catch the appraisal on the studio's monitors, he added a detail about the Hunter works: "The paintings have photos on the back."

Now this was interesting — very interesting. My camera crew had just returned from taping a field segment about Hunter at the LSU Museum of Art with another ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraiser, Kathleen Harwood. During part of their conversation, Harwood and Walberg talked about how Hunter's work had been faked over the years by several people. One imposter duo not only created phony works but concocted convincing (but false) provenance; a photograph of Hunter holding the counterfeit was sometimes attached to the back of the forgery.

Were the photographs on the backs of our ANTIQUES ROADSHOW guest's two paintings attached to authentic Hunter works? Or were they false witnesses, made to deceive? It would take more time to make that determination than our taping day in Baton Rouge allowed.

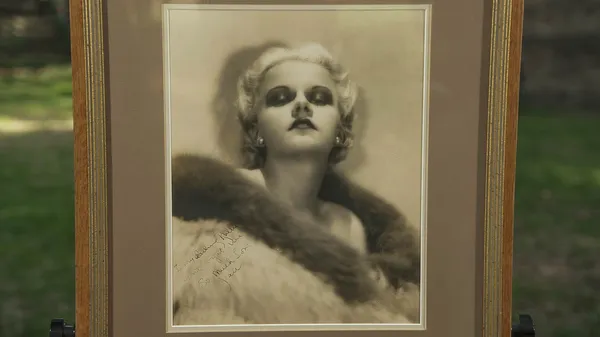

This Tom Whitehead photograph of Clementine Hunter appeared as the cover image for the 2012 book he wrote with Art Shiver, "Clementine Hunter: Her Life and Art." (Photo courtesy of Tom Whitehead)

An Artist's Beginnings

Clementine Hunter (ca. 1887–1988) was a self-taught artist. She had little schooling, and began working at a young age in the fields of the Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches (pronounced "nack-a-tish"), the oldest town in Louisiana, having been established in 1714.

In the 1930s, Hunter was a house servant and cook; by that time, Melrose plantation had become an artists' retreat under the direction of owner Carmelite "Miss Cammie" Henry. Hunter was likely exposed to painting for the first time. According to folklore about her beginnings as an artist, a plantation guest gave her some used paint tubes. From that point on, she painted obsessively.

Over the next several decades, Hunter created thousands of works, drawing upon memories and depicting a Southern way of life from her perspective as an African-American woman. In the beginning, she would charge as little as 50 cents for a painting. She painted right up until a few days before she died at 101 years of age, and by then her paintings could sell for hundreds of dollars apiece.

Today, Harwood puts the range of Hunter's paintings from under $1,000 for smaller works to around $10,000 at auction for her most desirable.

Digging In

Tom Whitehead is a leading expert on Hunter's work; he knew her personally. Because of his passion for her work — and to protect her legacy — Whitehead researches counterfeit Hunter paintings. In fact, he has collected a number of fakes that he uses to educate fans and collectors.

For ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's taping at the LSU Museum of Art, Whitehead loaned us a fake Hunter painting. It was an example of forgeries, he said, made by Joseph M. Henry (the son of Miss Cammie Henry, Hunter's long-time employer) and his wife Juanita.

As Whitehead explained, sometime in the 1970s Mrs. Henry would make counterfeit paintings and Mr. Henry would bring them to Hunter. He'd pay her a dollar or so, snap a picture of her holding the painting, and then attach the photo to the back of the forgery, according to Whitehead. The paintings subsequently would be sold at a nearby store for $50 to $150 — arguably a modest profit, but a profit nonetheless based on deception. The greater effect of their deception was that it tainted an artist's body of work.

One clue that helps collectors: "Not all the Henry fakes have a photo on the backside," Whitehead says, "but all have the same flat appearance. Mrs. Henry did not apply paint in the impasto style Clementine did. Certainly there are photos of Clementine holding original works, but not in the systematic way the Henry fakes are [presented]."

Why did Hunter seemingly go along with the charade? For one thing, she was in her 80s or 90s at the time. And as Whitehead speculated, "I would say Clementine just wasn't bothered by it. She sold everything she painted and never felt any competition. And I am not sure she fully understood what forgery was."

The Truth Revealed

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's event at the Baton Rouge River Center in July, appraiser Wes Cowan recalls seeing 15 to 20 works purported to have been done by Clementine Hunter. A guest named Teska brought in two of them; she had purchased them from a Louisiana dealer in the 1980s.

In looking at Teska's paintings, a couple of things stood out to Cowan: "[They] were accompanied by their original receipts and, most important, a photograph of Clementine Hunter holding the paintings."

As ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's cameras rolled, Cowan told Teska he felt her paintings were promising. If the two are real, he added, their value would be $2,000–$2,500 each at auction. But are they real? "You need to have them looked at by a Clementine Hunter expert," Cowan advised.

Normally, confirming the authenticity of an item appraised on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW is left for the guest to pursue. But because we had taped the field segment about Hunter and anticipated that Tom Whitehead would volunteer to weigh in on the paintings, ANTIQUES ROADSHOW took the unusual step, with Teska's permission, of trying to resolve the question right away. While she felt certain her paintings were genuine, Teska was happy to have Cowan's assessment corroborated.

The next step: After getting more information from Teska and talking to the dealer who had sold her the paintings decades earlier, I contacted Whitehead and sent along several high-resolution images of the paintings' fronts and backs (including the Polaroid photographs of Clementine Hunter holding the works).

Whitehead's response? He knew the woman who had sold the works to Teska and backed up the dealer's claim that she had bought from Hunter directly and had even attended Hunter's 100th birthday party. Whitehead also confirmed that the paintings looked authentic.

Teska, not surprisingly, was thrilled with the outcome.

One of two Clementine Hunter paintings brought by ROADSHOW guest Teska to the Baton Rouge event in July 2013.