Geronimo: Beyond the Name

Geronimo's name lives on in the folklore of the West. But who was he really?

Geronimo: leader, warrior, family man, and finally, prisoner. (Image source: Library of Congress)

Feb 15, 2008

At the San Antonio ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in July 2007, a man named Nash brought in a bow, arrows, and a quiver that was adorned with block letters that spelled a mythic name from America's Indian history: Geronimo. That name is now associated with a man who came to personify Indian resistance, fierceness, and pride. American World War II paratroopers leaping from airplanes yelled his name as a battle cry and kids eager to mimic his bravery still shout his name today.

"As a kid, jumping off a diving board or swinging from a tree," said Nash after the show, "we would say 'Geronimo!'" But who was the man behind this now legendary name?

Peaceful Early Days

The real Geronimo, whose given name was Goyathlay ("one who yawns"), was born around 1830 in what is now Arizona into an Apache group that had little contact with United States settlers.

Before his warrior days, Goyathlay worked with his father as a farmer, "where we broke the ground with wooden hoes," he wrote in his autobiography. "We planted the corn in straight rows, the beans among the corn, and the melons and pumpkins in irregular order over the field." As a child he played warrior, learning to make bows and arrows and to ride horses. After the war between the United States and Mexico ended in 1848, surveyors, whom Goyathlay described as "good men," visited Apache lands. He said they were "the first white men I ever saw."

By the 1880s the U.S. army had crushed all remaining Apache resistance in the West. Pictured, from right to left, Geronimo, Yanozha (Geronimos's brother-in-law), Chappo (Geronimo's son by his second wife), and Fun (Yanozha's half brother). Photographed by C. S. Fly, 1886. (Image source: Wikipedia.org)

A Warrior's Life — and Losses

Most of Goyathlay's adult life was marked by violence and pathos. While with a group of Apaches on a peaceful trading mission in Janos, Mexico, Mexicans ambushed and killed his mother Juana, his first wife Alope, and his first three children. After returning home, he was consumed by the fever for revenge. "I was never again contented in our quiet home. I had vowed vengeance upon the Mexican troopers who had wronged me, and whenever I ... saw anything to remind me of former happy days my heart would ache for revenge upon Mexico."

While mourning, Goyathlay heard a voice that said: "No gun can ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans, so they will have nothing but powder. And I will guide your arrows." In a subsequent battle with the Mexican cavalry, it is said Goyathlay fought so fiercely with his spear that the Mexicans began yelling the word "Geronimo" — the Spanish word for Jerome — perhaps beseeching help from St. Jerome. The name stuck, and fueled by anger, courage, and a wily strength, Geronimo would become one of the most feared of men among the feared Apache people.

Warring With Mexicans and Americans

From the 1850s through the 1860s, Americans, eager to mine silver, copper, and then gold in New Mexico, emigrated to Apache lands and settled there. War with the Apache ensued and the U.S. army moved in to protect the settlers. After the Civil War, the U.S. government decided to move all Indians living in Arizona and southwest New Mexico, including the Apache, to San Carlos in southwestern Arizona. In June 1876, when Geronimo and his Apache group were ordered to move to the reservation, they fled into the mountains of Mexico, where Geronimo continued to raid Mexican towns. Geronimo was captured when he and a small group of Apache were seduced into a meeting they thought was an entreaty for peace. They were brought to San Carlos, where prisoners were fed close to starvation rations and were exposed to new diseases such as smallpox. In 1878, Geronimo and his family and friends fled the reservation — and not for the last time.

Related: See historic life portraits of Geronimo by artist Elbridge Burbank

Final Surrender

Finally, U.S. Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles and 5,000 soldiers, at the time about a quarter of the U.S. army, hunted Geronimo and his band of 17 Apache through the Rocky and Sierra Madre Mountains. Chased for hundreds of miles, Geronimo surrendered only after he was promised that the Apache people would remain together. "I will quit the warpath and live at peace hereafter," he said. Geronimo would spend the rest of his life as a prisoner.

On September 8, 1886, 400 Apache Indians were crammed into 10 train cars and transported to Florida. Many died of tuberculosis. After a few years in Florida, the Indians, badly undernourished, were transported to the swampy Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama. Here, Geronimo made the painful decision to send Ih-tedda, one of his later wives (the Apache were polygamous) who was pregnant at the time, and their daughter Lenna, back to New Mexico. He would never see them again.

A Sedentary Prisoner

In 1894, Geronimo and the Apaches were moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, an army base where Geronimo dreamed of having a "farm, cattle, and cool water." Journalists would visit him there, sometimes asking to see the blanket that the warrior Geronimo had supposedly made from 100 scalps of those he had killed. There was no such blanket. Geronimo pleaded to everyone who would listen that the Apaches be allowed to return to the Southwest. "We are vanishing from the earth," he said. "The Apaches and their homes each [were] created for the other by Usen [the Apache life-giver] himself. When they are taken away from these homes they sicken and die. How long will it be until it is said, there are no Apaches?"

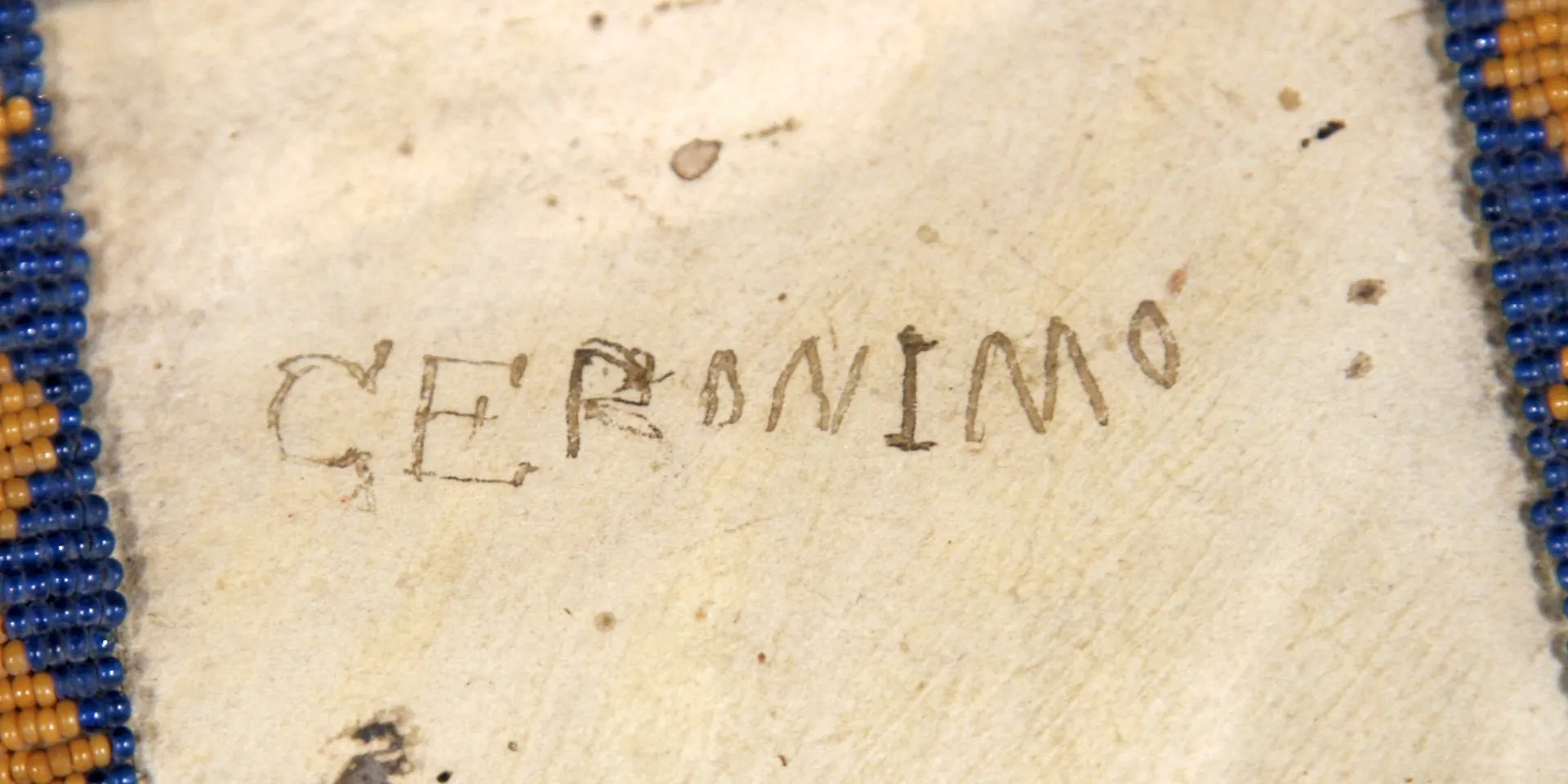

In captivity, Geronimo often signed Indian goods in order to make money.

Making Money From His Fame

Money was made from Geronimo's celebrity, and Geronimo quickly caught on, maneuvering for his share. In 1898, Geronimo was an attraction in the Trans-Mississippi and International Exhibition in Omaha, Nebraska, and he would make appearances in other events, such as St. Louis's World's Fair in 1904. "I sold my photographs for twenty-five cents, and was allowed to keep ten cents of this for myself," he said of the fair. "I also wrote my name for ten, fifteen, or twenty-five cents, as the case might be, and kept all of that money. I often made as much as two dollars a day, and when I returned I had plenty of money — more than I had ever owned before."

"I do not consider that I am an Indian any more," Geronimo would say. "I am a white man and [would] like to go around and see different places. I consider that all white men are my brothers and that all white women are my sisters — that is what I want to say."

Appraiser Bruce Shackelford believes that Geronimo did not make this bow, arrows, and quiver, though his signature is authentic.

Many objects with his signature have survived, including the quiver, bow and arrows that turned up in San Antonio. "I've seen his signature on little drums, on signed cabinet card photographs of himself," said Bruce Shackelford, who appraised the weapon. "I mean, this guy was early marketing personified. This guy was the celebrity. And he was the main celebrity. He had killed white folks and staked them over ant beds. He was a bad guy. ... He sold artifacts, and they didn't necessarily have anything to do with the Apache. People would bring him things he could sell, and they knew they could get more money for it with his signature, so they made a deal."

No Return Home

In 1905, Geronimo attended Theodore Roosevelt's second inaugural affair, hoping he could convince the U.S. President to allow him and other Apache to return to the Southwest. "I want to go back to my old home before I die," Geronimo told a newspaper reporter in 1908. "Tired of fight and want to rest. Want to go back to the mountains again. I asked the Great White Father [President Roosevelt] to allow me to go back, but he said no." To pass the time while in Oklahoma, he gambled in the card game monte, engaged in shooting contests, and bet on horse races. After his wife Zi-yeh, sick for some time with a tubercular infection, died, Geronimo took care of the domestic chores of his children and his extended family, washing dishes, sweeping the floor, cleaning the house, and treating the children kindly. He was devoted to his daughter Eva, born in 1889. One visitor said, "Nobody could be kinder to a child than he was to her."

The Final Days

By 1908, Geronimo had finally begun to show his age. His muscles withered. He became forgetful. On February 11, 1909, Geronimo headed into Lawton, Oklahoma, to sell some bows and arrows he had made. With the money earned, he bought some whiskey, got drunk, and rode home in the dark, cold night. He fell off the horse and landed in a creek; a passerby discovered him in the morning. He developed pneumonia. Geronimo asked that his surviving children be brought to Fort Sill during his final moments, but they were summoned with a letter rather than a telegram, and when they arrived he was already gone. He was believed to be 79. By the time he died, the Wright brothers had flown and the American Indian resistance had been crushed. He was remembered as a fierce warrior, a respected leader, a devoted family man, and finally, an unhappy prisoner who died on an Oklahoma reservation, selling his fame for cash while pleading steadily for return to his native Apache homeland. Now all that remains is his block-lettered signature, a gravestone graced with an eagle, and his memory — a symbol of Indian defiance and, finally, of subjugation.