How to Date an Old Horse...

What's a thermoluminescence test, and how is it used to authenticate ancient pottery?

Feb 15, 2008

At the July 2007 San Antonio ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, a woman named Pat brought in a Chinese horse from the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907 A.D.), which, if authentic, was remarkable for its large size and pristine condition. Pat explained that her husband had bought the horse in 1950 from an antiques shop in Tokyo while he was a soldier in the Korean War, and he paid for the magnificent statue on an installment plan, using cigarette packs to pay for most of it.

Pat had always believed it was authentic, and originally had brought the piece to the Atlanta ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in 1998. There, Lark Mason, an expert in Asian art, told her it was either an original from the Chinese city now known as Xi'an, or perhaps a very good copy. He recommended she have the clay tested using a scientific dating process called thermoluminescence.

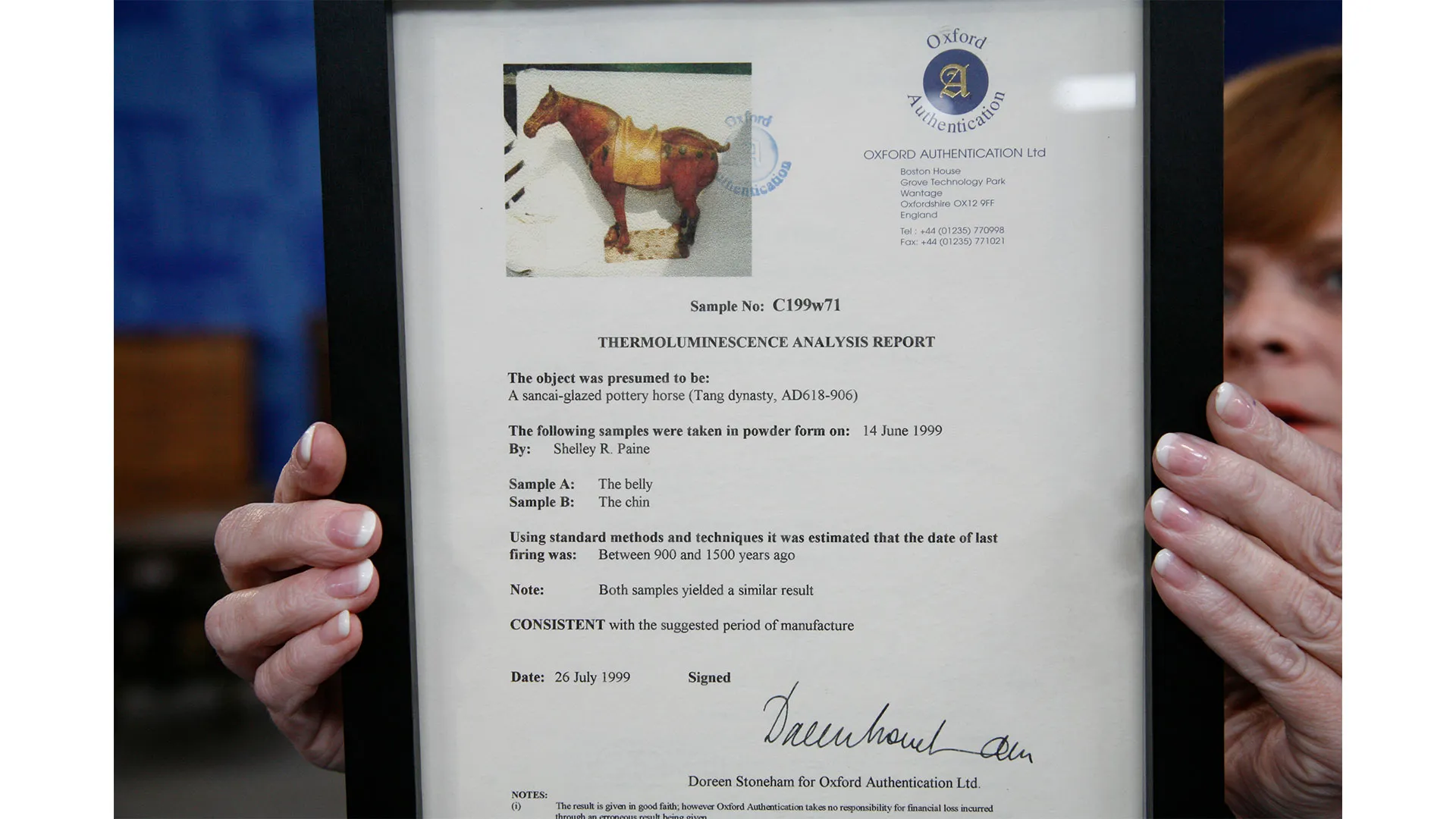

This Tang Dynasty Horse was unusual for its large size and pristine condition. In 1999, the owner had her Chinese steed scientifically tested with a sample from under the horse's chin and the belly.

Pat brought the sculpture to a woman who drilled two nearly invisible core samples—one under the horse's chin and another in the belly—and Pat sent the removed clay to Oxford Authentication Ltd., an English company that does more thermoluminescence tests on ancient pottery than any other firm in the world. Pat received a stamped certificate that described her piece and estimated that the "last firing was between 900 and 1,500 years ago." It was good news: The horse was authentic. That meant that Pat's horse was worth not a few hundred dollars—the value of a copy—but had an insurance value of about $80,000.

To find out more about the thermoluminescence process, which is being used more and more often to pin down the authenticity of clay antiquities, we contacted Doreen Stoneham, director of Oxford Authentication, for a Q&A about the process. Here's what we found out:

AR: How long has the thermoluminescence process been used to date pottery?

Doreen Stoneham: The thermoluminescence process was first used in the mid- to late-1960s. One of the first objects tested was called the "St. Louis Diana," a life-size Greek terracotta statue of the Etruscan goddess, reputed to be from the 5th century B.C. However, she wasn't.

It was initially tested in one place. When it proved fake, a few more small samples were sent from two to three selected areas. When these proved fake, small fragments were sent. In the end, I believe a whole arm was sent for testing. When I gave a lecture in the United States a few years ago, the curator of the St. Louis Museum was there and he stood up and said that despite all the testing, he still believed it was ancient! It now resides in the basement of the museum, I believe.

AR: Why would you need to test more than one spot on a piece?

DS: We do multiple sites because so many pottery pieces—particularly Chinese ones—are a pastiche, meaning they're "restored" by adding parts from several objects—a head from here, a leg from there, etc. We can frequently see using TL [thermoluminescence] that the clays are different. We can also see if there is restoration material or a modern addition to an ancient piece.

AR: With all that drilling, are there ever any mishaps?

DS: Remarkably few accidents have happened during drilling. The drills we use for ordinary clays are dental drills used for root-canal drilling—the point is very fine and very painful if it goes through your thumb. They are around two millimeters in diameter at the business end diminishing to needle-fine. Porcelain is cored using a diamond core drill around four millimeters in diameter. The speed of the drill is as slow as possible to give us more control and to minimize heating. We take 100 milligrams of powder and use that for the TL test after careful washing and preparation.

We must have sampled 80,000 to 100,000 pieces, and accidents—usually the drill, which is as fine as a pencil point, going through the surface or chipping an edge—can be counted on the fingers of one hand. Despite people's fears, pottery is very robust and does not spontaneously shatter.

AR: How does thermoluminescence work and are there false positives or negatives?

DS: TL measures the amount of natural radiation absorbed over the lifetime of an object and from this an approximate date is obtained. For a more detailed explanation of TL, see https://www.oxfordauthentication.com/

False positives can occur in the case of deliberate insertion of genuine fragments into modern pieces—notably, bases in porcelain. We have found shards inserted into glazed pieces—the shards being unglazed as the forgers know that we do not usually drill into a glazed area, so they guide our hand, so to speak. There are also pieces on the market which have been artificially irradiated so that they are exposed to approximately the same amount of radiation as the pot will have absorbed over its life time. The list of forgers' tactics is endless. The forgers, particularly the Chinese ones, are very ingenious, and as soon as we discover one scam, they start another.

AR: How precisely can TL pin down the age of an object?

DS: [When] an object is excavated, a whole lot of information regarding the natural radioactivity, wetness, and other characteristics of the burial surroundings can be measured before it's removed. This gives a theoretical error limit of plus or minus six percent of its actual age. In practice, though, I've never found better than plus or minus 10 percent, under the best conditions. When we are authenticating, we can be very precise with measurements and preparation, but information regarding the burial conditions is often missing, so we say we can provide plus or minus 20 percent of its actual age—which is a 40 percent spread. That's quite sufficient in most cases to determine authenticity. The most probable age lies somewhere between these limits, but it's equally likely to lie anywhere at either end as it is in the middle. Ninety-two percent of what we test is either consistent with the attributed age or is modern. Of the remaining eight percent, a small proportion lies at either side of the limits, which is statistically valid. The rest either cannot be dated because the clay is unsuitable, or is misattributed.

AR: What do you mean by "unsuitable or misattributed"?

DS: Clays can be unsuitable for a number of reasons. In order to give a good TL signal, they should contain quartz and/or feldspars, which are known as TL minerals. If they are deficient in these minerals, the signal is too weak to measure. The clay might also contain non-TL minerals, which decompose on heating and swamp the archaeological signal. We then get a "spurious" signal that can't be dated. The sample might also contain soil, which is unfired, and we then get an age that is millions of years old, corresponding to a geological age. The sample might also be from a restored area which gives a spurious signal.

AR: Thermoluminescence is obviously a useful tool, but can it be completely relied upon?

DS: TL is the only truly absolute scientific dating method for fired clays. The process has its drawbacks, but it's absolutely independent of "expert" opinions. The problem is not the dating of the clay... but the amount of restoration or forgery—call it what you will.

Ideally, the piece should be CT scanned or X-rayed to look for breaks and joints. The pigments should also be analyzed to look for modern materials, although false positives occur there as well as the forgers know exactly what to use and avoid. The clay should also be examined for the presence of organic materials, which, if found, can indicate a restoration, remodeling of powdered ancient clay or a more innocent consolidation of the surface.

As you can imagine, dealers don't always want so many examinations of their pieces (Oxford charges $400 to assess each object using TL). Apart from costing money, any one of these extra examinations can throw up doubts on the piece.

My personal feeling is that any method that throws some light on the authenticity is better than none—and much better than relying on the vendor's opinion. My problem is that people have come to rely on us to police this small aspect of the art market while at the other end of the scale, the forgers know what to do to get around the testing. I would like to reassure collectors that we scrutinize each result as well as the object to see if there is any aspect we're unhappy with. In many cases, we again demand another sample from very specific regions of the piece to see if it matches the previous samples.

You may be interested to know that the first thing we tested when I set up this company [Oxford Authentication Ltd.] in 1997 was for ANTIQUES ROADSHOW [the British version]. Unfortunately, it proved to be a modern 19th-century piece rather than a hoped-for 16th- to 17th-century one!

Pat received this document from the authenticating company verifying the good news — that her horse could be dated to a time falling within the Tang Dynasty.