Huey Long's Life and Legacy

How did Huey P. Long stay in power amid scandals and accusations of corruption and why is his shadow still so hard to escape over eighty years after his death?

Feb 24, 2014

Just after he was married, in 1913, a 19-year-old Huey P. Long told his wife about his plan: He was going to run for and be elected to a minor state office, then win the governorship, become a United States senator, and finally be elected president of the United States. It's a common career plan for aspiring politicians, and Long set about achieving it with astonishing single-mindedness and, it must be said, disregard for the law. His flamboyant populism and willingness to make outlandish promises inspired worship among voters, and disgust mixed with ridicule from critics. "It's all very well for us to laugh over Huey," President Franklin Roosevelt once said, but "he really is one of the two most dangerous men in the country" (the other being Gen. Douglas MacArthur).

Even now, almost a century later, Huey P. Long's enigmatic shadow is hard for Louisianans to escape

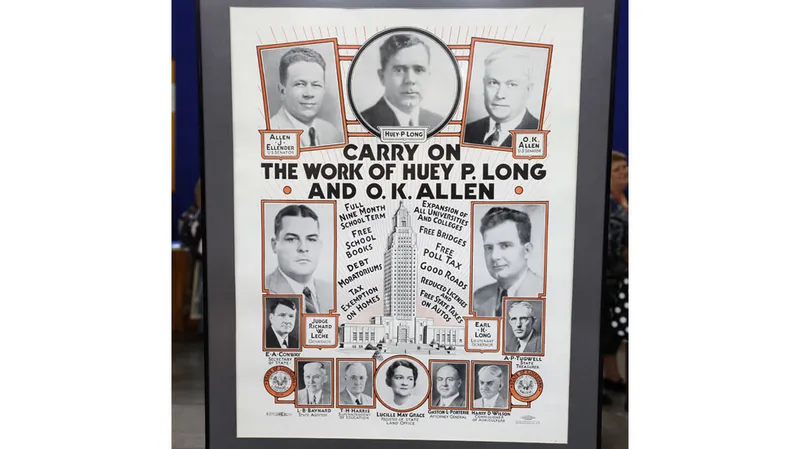

Before Long could mount a challenge to Roosevelt, whom he saw as a weakling and a phony, he was assassinated, in a hallway of the very capitol building he had ordered constructed as a monument to his own grandiosity. Nicholas Lowry, of Swann Gallery in New York, appraised the poster brought to the Baton Rouge ROADSHOW in July 2013, featuring Long and his successor as governor, O.K. Allen, among many other Louisiana politicians, at between $3,000 and $4,000. By the time of the poster's printing, Huey Long had been dead for at least a year, but his political influence had not waned. Even now, the better part of a century later, Long's shadow is hard for Louisianans to escape.

Huey Long was born into a poor farming family in 1893. From his father, a socialist and failed politician, Long inherited an aggressive populist streak, and from his mother, a slight, self-educated woman with the memorable name Caledonia, a photographic memory. As one of nine children, Long must have felt constant pressure to attract a share of his parents' attention; from the time he could walk, he sought to dominate and control his surroundings. As an adult he dressed outrageously, even when he was in the United States Senate, wearing lavender shirts, pink floral-print ties, and a flower in the lapel of his double-breasted plaid suits — a Technicolor gangster, right down to the two-tone wingtips. "Drama," a Long supporter recalls in Kingfish, Richard White's biography of the politician, "was his natural art."

Huey P. Long, "The Kingfish," mid-oration, February or March 1935. (Image source: Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress)

After serving briefly on the Louisiana Railroad Commission — his "minor state office" — Long ran for governor in 1924. With the newspapers and the urban political establishment against him, he lost. In 1928, he ran again, successfully this time. During the campaign, Louisiana got a taste of what the next seven years under Long's rule would be like. When Long encountered an adversarial newspaper editor on the street, he assaulted and bloodied him. Later, Long had a chance meeting with the sitting governor in a hotel lobby. When the governor, a 60-year-old man, accused Long of being a liar, Long punched him in the face.

From the stump, Long presented himself as a saintly, spirit-filled man of the people. He waved his arms and pounded the lectern. He accused his rivals of moral turpitude. He promised the moon to the poor. He would bring them roads, books, and education, and stand up for them against big business, particularly the Standard Oil Corporation, whom Long likened to the Ku Klux Klan. On election day, Long performed abysmally in the cities. But he more than made up for that poor showing in the parishes, where he polled up to 70 percent of the vote. It was more than enough to see him elected governor.

As soon as he was in office, Long decided he could not abide living in Louisiana's decrepit, if historic, governor's mansion. So he called up the warden from the state penitentiary down the road and ordered him to send a crew of convicts to the mansion to demolish it.

During the first part of his political career, Long made his reputation as a champion of the downtrodden. He bullied and bribed his political adversaries in order to secure free schoolbooks for Louisiana schoolchildren, lay 9,000 miles of roads, build over a hundred bridges, and through adult education courses teach 175,000 illiterate Louisianans to read. In the process, he brought the state within spitting distance of bankruptcy, damaging Louisiana's economy so severely that state bonds became worthless. Long certainly had some measure of compassion for the poor, but they were increasingly a means to an end. With a permanent constituency of worshipful, rural supporters — "the boys at the forks of the creek," in Long's phrase — he could do what he liked. If the proletariat were so satisfied that they had "no complaint," Long said, "a perfect democracy can come close to looking like a dictatorship."

When Long was brought up for impeachment in the Louisiana legislature on corruption charges, he used the tyrant's playbook to subvert the trial. He ordered state employees to attend anti-impeachment rallies. He lured an influential Baptist minister into a hotel room, where there was liquor and a prostitute, in order to extract his public support. The House impeached Long. But the men in Louisiana's Senate, many of them bought off with "promises, threats, bribes, liquor, [and] women," dismissed the charges.

Long had escaped being thrown out of office. But his biographers note that the impeachment ordeal changed him. From then on he sought and exercised power for its own sake. He brazenly miscounted legislators' votes. He blackmailed and intimidated adversaries. He required construction contractors doing business with the state to kick back 20 percent of their fees to his political machine. He diverted wealth from Louisiana's oil resources to his allies. He had become "the first true dictator out of the soil of America," in the words of the journalist Hodding Carter. "Give me the militia," Long said, "and they can have all the laws they want."

In 1930, with two years remaining in his term as governor, Long ran for the United States Senate. Every daily newspaper in Louisiana opposed him, and his political enemies were determined to keep him from joining the most powerful body in American politics. To silence a particularly bothersome pair of critics, Long had his henchmen break into their hotel room in the middle of the night and kidnap them; according to one, Long tied them to a tree. On election day, indications of voting fraud were ubiquitous. "In one St. Bernard parish," writes Richard White in Kingfish, "the official record indicated that voters marched to the polls in alphabetical order." The rolls included the names of "Clara Bow, Babe Ruth, Jack Dempsey, and Charlie Chaplin."

Again calling on the goodwill of Louisiana's lower-middle class, as well as his own manipulation of the democratic process, Long was elected to the Senate. Once there, he delivered endless, rambling speeches on the redistribution of wealth that were not designed to persuade other senators, but to raise his own profile. He was preparing his run for the presidency. To that end, he published a fantastically venal book called My First Days in the White House. "It had happened," the book begins. "The people had endorsed my plan for the redistribution of wealth and I was president of the United States. … [I] looked into the face of the retiring president. He seemed worn and tired. … He shouted something in my ear but his words were drowned by the roar from the crowd." To the New Yorker's James Thurber, Long claimed, "I've saved the lives of little children, I've sent men through college, I've lifted communities from the mud, I've cured insane people."

Long's crony O.K. Allen succeeded him as governor, but Long couldn't take his hand off the wheel. Whenever he returned to Louisiana from Washington, he had Allen move to a secretary's office so he could occupy the governor's chair again. Long continued to exercise his control over the state. To defeat an enemy's bid for the mayoralty of New Orleans, he sent two of his henchmen into the state registrar of voters, armed with revolvers and red pens, with which they crossed undesirable voters' names off the rolls. After they were caught in the act, Long ordered Louisiana's entire National Guard, armed with rifles, to invade the city. To repel the invasion, the mayor armed city police and mercenaries with machine guns and tear gas. It is remarkable that no shots were fired.

Later, when a newspaper reported an inside scoop on Long's policies, a drunk Long ordered the National Guard to storm the paper's office and destroy its presses. "I've been under the influence [of liquor] more nights of my adult life than I've been sober," he confessed to a bodyguard, "and out of this have come some of the most brilliant ideas of my career." Long sobered up in time to belay the order, but later followed through on a similar threat to a college newspaper that had published an unfavorable editorial, sending state police to destroy 4,000 copies of the paper. "That's my university," Long said. "I built it, and I'm not going to stand for any students criticizing Huey Long."

Huey Long didn't live long enough to complete his plan and run for president. In September of 1935, he returned to Baton Rouge to make sure legislators “voted right” on a bill that would remove a political opponent named Benjamin Pavy from his judgeship. After Long left the chamber in a bad mood, Judge Pavy's son-in-law, a slender, dark-haired man named Carl Weiss, broke through Long's wall of bodyguards with a revolver. Months prior, Long had accused Weiss's wife — Pavy's daughter — of being of mixed race (having “coffee blood”). Then, out of malice, he'd had her uncle fired from his job as high school principal, and her sister fired as a third-grade teacher. Perhaps in retaliation, Weiss shot Long in the chest. Long's bodyguards immediately fired 62 bullets into Weiss's body, killing him. (A persistent but less prevalent view is that Weiss, who had no history of violence, was not carrying a gun and did not shoot Long at all. In this version of events, Long's bodyguards overreacted to Weiss' aggressive badgering of Long, and Long was killed inadvertently by his own bodyguards.) The state physician who treated Long's wound had been appointed by Long when he was governor — to a position for which he was unqualified — and botched the surgery. Huey Long died two days later.

To some, Long's actions have come to seem like the antics of a charming rogue, his life a welcome splash of color in the dull history of American politics. He fired a drawbridge attendant who was an acquaintance of a political enemy! He fired a policeman who gave his son a speeding ticket! "Huey Long was the most entertaining tyrant in American history," read a review of Kingfish in the Washington Post. But Long wrought real damage on Louisiana and on the lives of Louisianans, even the ones he claimed to want to help. He opposed progressive legislation on child labor, the minimum wage, sweatshops, and unions, once threatening the streetcar workers' union with the National Guard. In 1930, Long prophesied that economic revival would soon sweep over the state. "Growth will be almost magic," he said. But per capita income fell by half under his rule. The "boys at the forks of the creek," to whom Long made such extravagant promises, saw farming incomes plummet 66 percent. Long increased taxation by 75 percent, but through his profligacy caused Louisiana's debt to grow from $11 million to $150 million. The roads, schoolbooks and bridges Long delivered to the poor of Louisiana were less an emblem of some deeply felt populism than of the tragically low status accorded the poor.

In a culture that rewarded wealth with political influence, the support that the have-nots gave Long makes sense. "At least we got something," said one Louisiana farmer. "Before him, we got nothing. That's the difference."

Nicholas Lowry appraised this ca. 1937 Louisiana political poster at between $3,000 and $4,000.