Jack Johnson: World Champion, and the "Most Polarizing Figure in America"

Born the son of formerly enslaved parents, Jack Johnson turned to prizefighting to battle his way out of poverty, eventually becoming world champion. For white Americans of his time, however, Johnson was a threat.

Jan 27, 2020

BY Louis Moore

BORN ON MARCH 31, 1878, in Galveston, Texas, the son of formerly enslaved parents, Jack Johnson would grow up to become the world heavyweight champion (1908-1915), but in so doing he also became the most polarizing figure in America.

With his success in the ring — along with his attitude outside of the squared circle, which ignored racial norms of the times — many black Americans saw Johnson as a hero who tried to conquer Jim Crow. Many white Americans, however, saw Johnson as a threat. For them, he was public enemy number one.

Refusing to live the life of servile menial labor that awaited most black Americans, Johnson turned as a teenager to the sport of prizefighting to battle his way out of poverty. On his way to the top, he defeated some of the greatest fighters of all time, including Sam Langford, Sam McVey, and Joe Jeannette.

The racism these men faced both in society and the sport of boxing fostered resentment that they turned into a controlled rage, making them some of the fiercest fighters ever. Johnson, who won the colored heavyweight championship in 1903 when he defeated “Denver” Ed Martin, beat them all. But Johnson was never just satisfied with being the colored champion, he wanted to be champion of the world.

The Color Line in Boxing

In 1882, when Irish-American John L. Sullivan won the heavyweight crown, he stated that the belt had too much prestige for a black man to fight for and instituted a strong color line. Soon other sports, including baseball, horse racing and cycling would search for ways to “Jim Crow” black athletes. In boxing, until 1908, all the white heavyweight champions, including luminaries like Jim Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, and Jim Jeffries, followed suit. Jeffries, in fact, retired undefeated in 1905, claiming there were no more good white fighters to face.

But Tommy Burns was a fighter who cared more about money than the color line. In 1908, the Canadian agreed to fight Johnson for the world championship. Burns, who told the public that he would defeat Johnson because black fighters were cowards and were more susceptible to body punches because they had hard skulls, miscalculated his racism. On December 26, 1908, in Sydney, Australia, Johnson dominated Burns, forcing the referee to stop the fight in the 14th round.

Life with No Bounds, and the "White Hope"

Johnson’s championship victory ignited an ire in white Americans. Johnson lived his life with no bounds. That is to say, he lived free during a period when black Americans were expected to display due deference toward the discriminatory laws of the day. Johnson dressed in flamboyant clothes, wore gaudy jewelry, drove expensive cars paying no attention to speed limits, went where he wanted even if that meant crossing the color line, and worst of all for white America, he openly dated white women.

At a time when just the insinuation that a black man had looked at a white woman could lead to a lynching, Johnson flaunted his love life with little worries of what whites thought. Seething with anger after Johnson’s victory, famed American novelist Jack London wrote an open letter in the press begging Jim Jeffries to unretire, defeat Jack Johnson, and “remove that smile from Johnson’s face.”

London’s letter, Jeffries’ immediate refusal to fight, and America’s desperation, set off a failed search for a “white hope.” In one fight, promoters trotted out the “Michigan Assassin,” Stanley Ketchel, an all-time great light-heavyweight, but a man who was clearly no match for Johnson — who had more than 30 pounds on his opponent. The fight ended with a 12th-round knockout (and Johnson slowly removing Ketchel’s teeth out of his boxing glove).

The failure of the white hopes shifted all the pressure back on Jeffries to save the white race. As Jeffries told a reporter, “I decided to meet Johnson to regain the title of champion heavyweight of the world, to win back for the white race the title which the other fellow allowed to be wrestled from him.” He was their last hope, but after five years of retirement, he did not stand a chance.

Johnson vs. Jeffries, and the Aftermath

The Johnson-Jeffries bout, which took place in Reno, Nevada on July 4, 1910, is the most significant fight in American history. It was billed as a battle of racial superiority, with one editorial from Marysville, California, worriedly asking, “If the negro wipes up the earth with Jeffries will this country belong to the coons? Will we be forced to repeal the 13th, 14th, and other amendments to the constitution for self-protection?”

Nearly 20,000 fans showed up to Reno to watch the affair, and hundreds of thousands more Americans ventured to the closest venues providing live telegraph updates of the fight. Johnson outclassed Jeffries en route to a 15th-round stoppage. As one headline in the San Francisco Chronicle described, “White Giant Beaten Down By Ebony Fighting Machine.”

In the aftermath, black fans across the country took to the streets to celebrate Johnson’s victory, while white people looked for revenge. In Alabama, whites shot out a black woman’s tongue, and in New York they tried to lynch a black man. All told, an estimated 19 black people were murdered in riots across the country as a direct result of Johnson’s victory.

Worried about more riots, and unwilling to accept reality, many cities across the country banned theatres from showing film of the fight. Two years later, after Johnson defeated “Fireman” Jim Flynn, Congress banned the interstate transportation of all fight films. Even worse for white Americans, in 1911 Jack Johnson married Etta Duryea, one of his many white lovers. Concerned that Johnson’s behavior would trickle down to other black men, Congress debated passing a law to outlaw interracial marriages.

Mann Act Conviction, and Johnson's Legacy

Incapable of defeating Johnson in the ring, and unable to control Johnson outside of it, lawmakers took things into their own hands. In 1912, a month after Duryea committed suicide and Johnson started dating another white woman, Lucille Cameron — whom he would eventually marry at the end of the year — the government charged Johnson with violating the Mann Act.

Congress passed the law in 1910 to abolish prostitution by outlawing the transportation of women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” On shaky evidence, in 1913 the government convicted the champion of violating the Mann Act. Instead of complying, Johnson went into exile and moved to Europe.

Unfortunately for Johnson, the start of the Great War forced him to flee again. Desperate for money, and to return home with a clean slate, Johnson fought Jesse Willard in Havana, Cuba, in 1915. Johnson always maintained that he threw the fight to Willard, suggesting the government had told him they would drop the charges if he lost his title. No such deal was arranged.

Defeated, Johnson remained in exile, primarily living in Mexico, until he turned himself in to U.S. officials in 1920. Fearing the next Jack Johnson, a black man was not allowed to fight for a title again until 1937, when Joe Louis defeated James Braddock. By the 1930s and 40s, Johnson’s popularity began to wane with the rise of other superstar black athletes like Joe Louis, Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson, who became symbols of integration and American democracy. But his story continued to weave itself through American history.

Although his 1946 death in a car crash brought underwhelming coverage from newspapers, by the 1960s, Jack Johnson’s legacy was beginning to grow. His story represented a rebellious spirit that matched the politics of that decade. He has since remained popular as an anti-hero who challenged Jim Crow and unfairly felt the full weight of his government. In 2018, President Donald Trump posthumously pardoned Johnson for his Mann Act conviction — an apology more than 100 years overdue.

Related

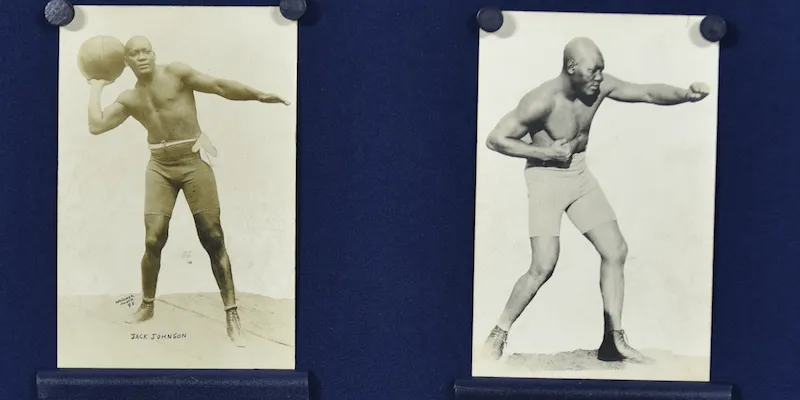

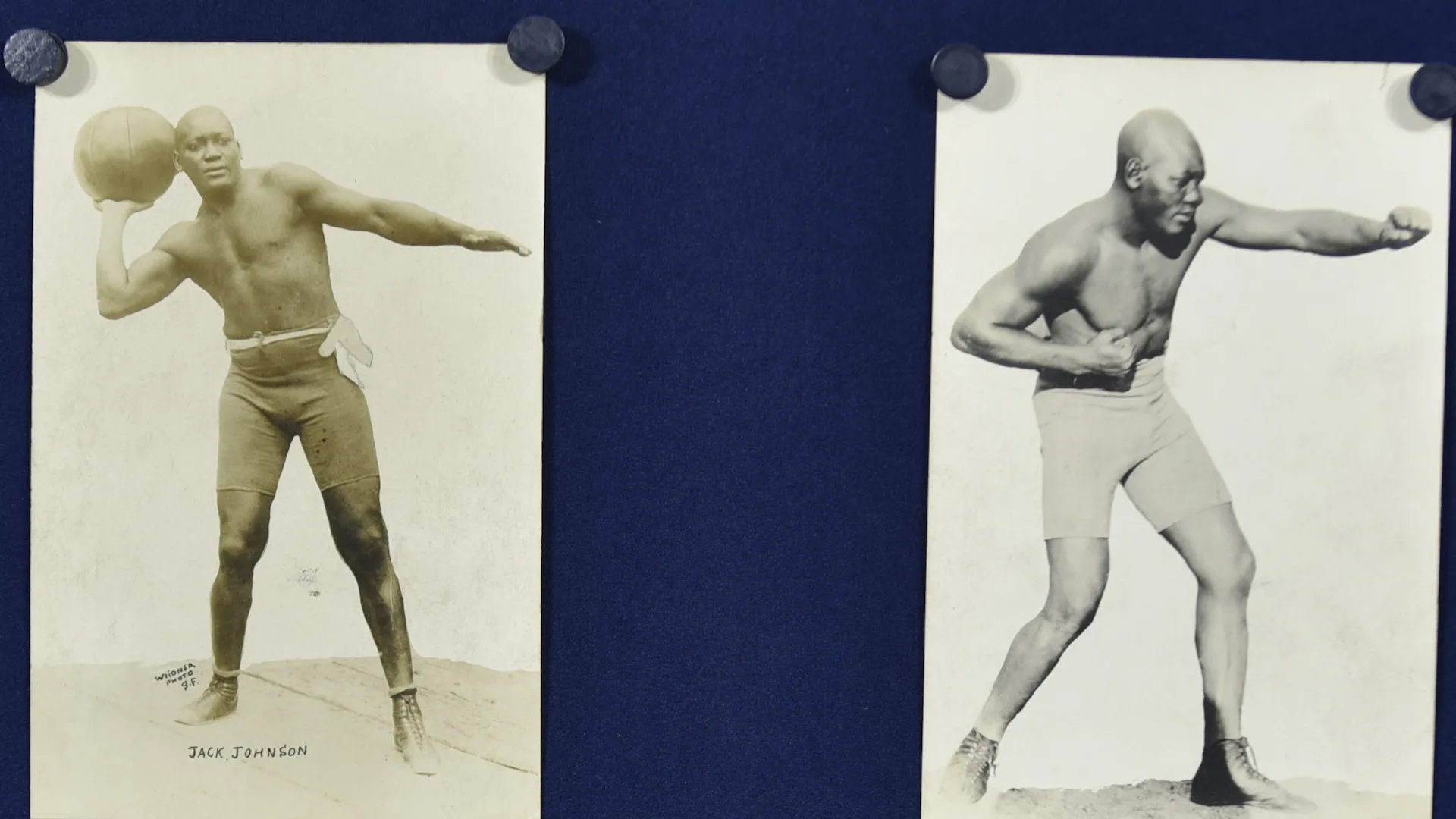

See Grant Zahajko's appraisal of a collection of ca. 1910 photographic boxing postcards in our Appraisals Archive

Sports Memorabilia expert Grant Zahajko appraised these and two other ca. 1910 boxing photo postcards in Bonanzaville for between $2,300 and $3,000 at auction.