Keith Haring: How Graffiti Entered the Mainstream

Keith Haring was ever an outsider to the art establishment in his lifetime, but since his death in 1990, his legacy as an artist of historic importance has only become more secure.

Jan 29, 2018

Originally published on: Oct 26, 2015

BY Ben Phelan

When the art installation Dismaland Bemusement Park opened in August of 2015, it did so with all the fanfare normally associated with a work of high art — a Cy Twombly installation perhaps, or one of Christo and Jeanne-Claude's draped monuments. There were notices in The New York Times and The Guardian, radio essays on NPR, and hype throughout the art world. The artist responsible was Banksy, whose real name and identity remain a mystery. He is one of the art world’s only superstars; but his approach to art is inimical to the idea of museums and galleries, and even to the indoors.

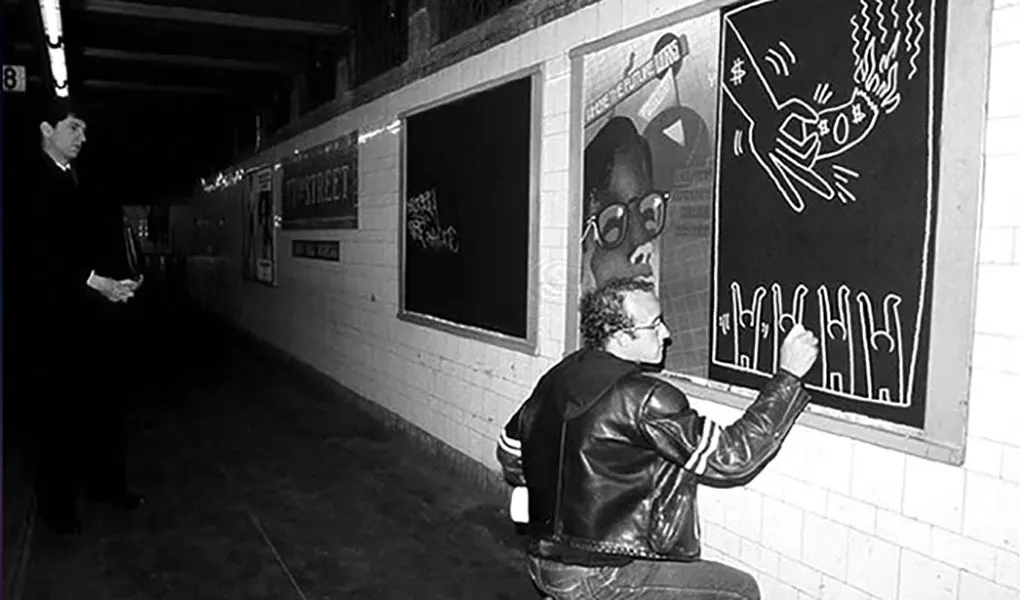

Keith Haring created his art in public places like subway stations, rather than more formal, academic settings. People left his art alone, even his fragile chalk drawings like the one above. Image source: publicdelivery.org.

Banksy is, in short, a graffiti artist. That he is not considered strictly as a criminal, but as something a bit more complicated, owes equal amounts to his trenchant sensibility and dark whimsy as to another graffiti artist, Keith Haring, who crossed into the mainstream.

Keith Haring came of age in New York City in the early 1980s, long before the economic boom of the 1990s (and its harsher policing practices) conferred (or imposed) on downtown Manhattan the respectability it now possesses. In Haring's New York, neighborhoods such as the Lower East Side and the East Village were rough and sometimes unsafe, but the cost of living was low, and the streets were full of people. Haring had moved to New York to study art in an academic setting, but found the city itself a more vibrant venue for art than the clean white walls of the city's galleries.

The energy and immediacy of graffiti — public art, as its supporters prefer — seized and colonized Haring's imagination.

At the School of Visual Arts, Haring studied art in the standard academic tradition. His studies provided him with a formal understanding of art, but it was in the subways that he found his inspiration. The walls of the subways and the outsides of the trains were covered with glyphs, initials, sketches, cartoons — an impenetrable text of symbols that seemed to represent the lived experience of the city much more immediately than the formal art world would allow.

Down in a subway station one day, Haring's attention was drawn to an empty rectangle of unused advertising space on the wall. The paper was soft and inviting, and pure black. Haring ran up the stairs, then down the street to a shop, where he bought a box of chalk, then back down into the subway system to draw. In the heart, or perhaps the bowels, of the city, where thousands and millions passed day in and day out, Haring had found his gallery.

Because these liminal black spaces were so fragile and surrounded by hostility or at best indifference, Haring said, people left his art alone. "They didn't rub them out or try to mess them up. It gave them this other power. It was this chalk-white fragile thing in the middle of all this power and tension and violence that the subway was. People were completely enthralled."

The energy and immediacy of graffiti — public art, as its supporters prefer — seized and colonized Haring's imagination. As he drew and sketched and doodled, a menagerie of figures, influenced by the short, quick strokes on the subway walls, flowed from his hand. "They were humans and animals in different combinations. Then flying saucers were zapping the humans. I remember trying to figure out where this stuff came from, but I have no idea. ... I was thinking about these images as symbols, as a vocabulary of things."

One of Haring's most recognizable images is a cartoon of a baby on all fours, surrounded by light. The "Radiant Baby" or "Radiant Child" is perhaps indistinguishable, on the surface, from graffiti you'd find on any building in any modern city. But the figure is also known as "Radiant Christ," which connects Haring's sensibility not only with his own deep moral sense, but also with two millennia of artistic depictions of the Savior. In his youth, Haring had been an evangelical Christian. When he was becoming an artist in New York City, the redemptive power of Christ was still a powerful image for Haring. Though by then he was far from a conventional Christian.

Another of Haring's most famous images, a sperm with horns, or "Devil Sperm," reveals how much his sense of spirituality had changed by the mid- to late-1980s. At the time, the scope of the AIDS crisis was clear to gay men living in New York City, such as Haring, but society had yet to fully recognize it. President Ronald Reagan was conspicuously silent on the subject of the disease, seemingly uncomfortable with its connection to gay sex. There were public concerns about toilet seats and the sharing of water glasses. In 1987, Haring learned that he, like many of his friends and peers, had contracted AIDS. His work was soon permeated with horned sperm, a symbol that linked physical love with death. As an artistic gesture, this was hardly new, but in Haring's rendering it was immediate and direct. At the time, Haring had risen to superstardom in the art world. When he went public with his diagnosis, his celebrity helped to normalize AIDS and rob the disease of its stigma as a "gay plague," as it was once known.

Keith Haring died of complications related to the disease on February 16, 1990, when he was only 31. Since his death, his reputation as an artist of historic importance has only become more secure. Like Jean-Michel Basquiat had done before him, Haring sought to erode the boundaries between the public, for whom art functions as conscience and subconscious, and the galleries that keep the public away by connecting art with money. The collection of Haring ephemera Betty Krulik appraised at the Chicago ROADSHOW completes the circle: It brings us into direct contact with an artist who believed contact with the public was art's highest virtue.