Madam C.J. Walker: Hair Care Millionaire

More on the life and work of Madam C.J. Walker, cosmetics entrepreneur, philanthropist, and America's first self-made female millionaire.

Apr 7, 2014

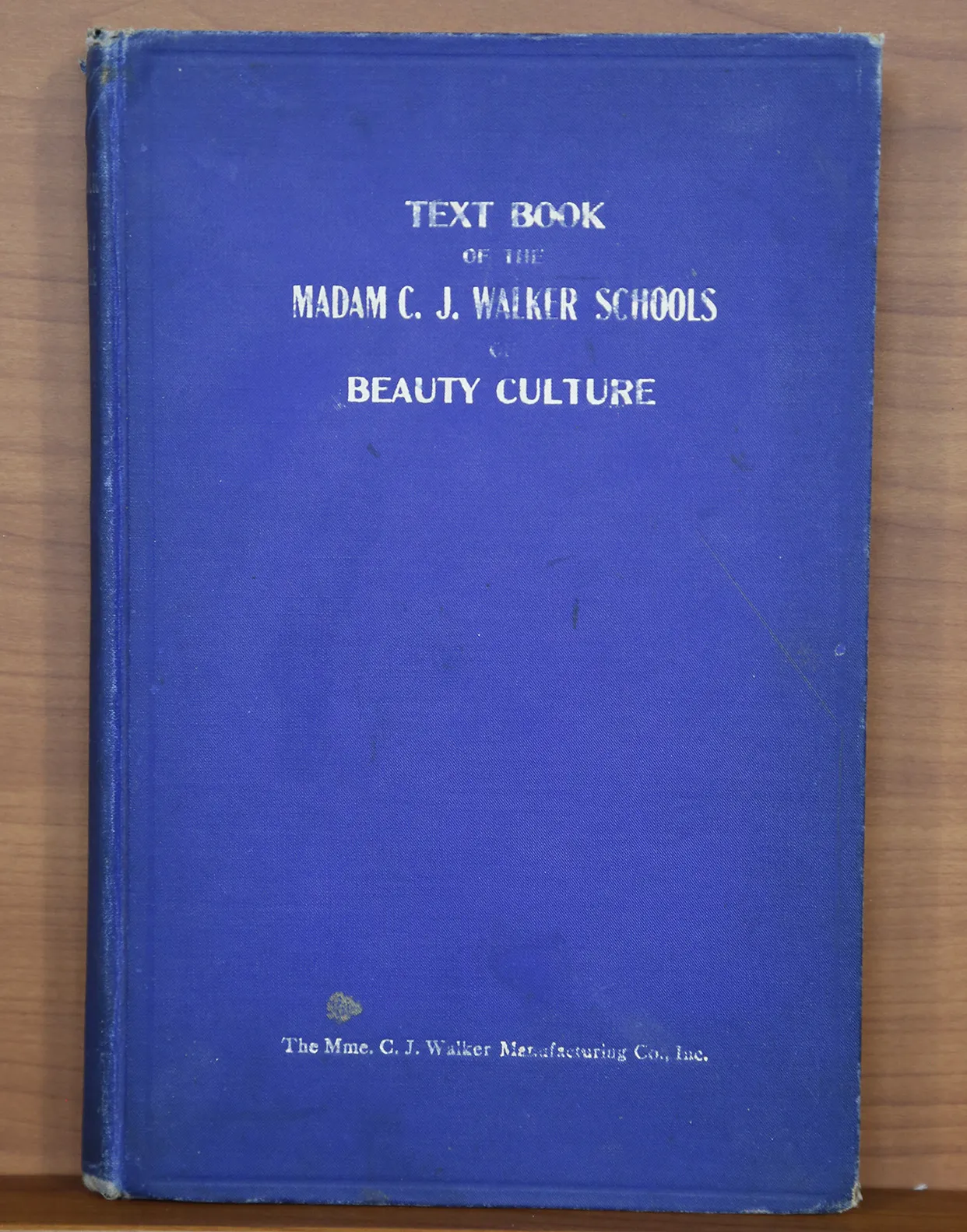

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW's Kansas City stop in 2013, hairdresser Loretta L. of Independence, Missouri, brought in a blue book titled Text Book of the Madam C.J. Walker Schools of Beauty Culture (1928). She'd received the book as a gift from a friend and had tested a few of the home remedies listed within, but otherwise knew very little about it. Appraiser Ken Sanders identified it as a first-edition copy of a hair-care book by Madam C.J. Walker, often referred to as America's first female self-made millionaire. The book — the very first published for hair styling and fashion for African-American women — was appraised at a retail value of $10,000.

Portrait of Madam C.J. Walker, ca. 1913. She marketed a number of successful cosmetic products. (Image courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives/A'Lelia Bundles.)

Early Life

Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867 — four years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and only two years after the end of the Civil War. The daughter of freed slaves, she grew up in a small cabin on a Louisiana plantation. In 1878, Breedlove moved with her sister's family to Vicksburg, Mississippi, to escape growing anti-black violence in Louisiana. It was here, at age 10, that she found employment as a washerwoman. Breedlove was a wife at age 14, a mother at 17, and a widow at 20. Facing an unsure future, Breedlove moved with her daughter to St. Louis, where she encountered an African American working- and middle-class she'd not seen before.

Cosmetics Pioneer

It was in St. Louis where Breedlove noticed that women who were widely respected and were working their way up the social strata usually had longer flowing hair. "Appearance correlated with prosperity," as A'Lelia Bundles (Breedlove's great-great-granddaughter and biographer) put it in On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker.

Unfortunately, in the mid-1890s Breedlove's own hair started to fall out — and she was not the only one. Many other women of her day also suffered this malady, caused by infrequent washing, poor diet, and damaging hair treatments. History is a little unclear, but it's probable that Breedlove's hair and scalp problems were solved by treatments from Annie Pope-Turnbo, a local African American entrepreneur who had started her own hair-care company a few years earlier. (There's some controversy as to how much Breedlove ultimately borrowed from Pope-Turnbo's methods, and whether more credit is due to her.)

What is known is that Breedlove joined Annie Pope-Turnbo as a sales agent for her scalp products. Pope-Turnbo taught Breedlove that "Better appearance means greater business opportunities, higher social standing, cleaner living and beautiful homes."

In 1905, Breedlove headed west to Denver, Colorado, to sell Pope-Turnbo's products, and while there, she began experimenting with her own versions of the product. Breedlove opened a hairdressing business, and began advertising widely. When she married Charles Joseph Walker in 1906, Breedlove adopted his name and added "Madam," to give it an extra flair.

Entrepreneur

Soon thereafter, she broke ties with Pope-Turnbo and started a business selling her own product under the name "Madam C.J. Walker." With a great business and promotions sense, Walker began traveling, performing her scalp treatments and teaching others. Madam Walker determined that the rural South and the Northern cities were the best sales locations, and she trained and treated several hundred agents and clients. Her southern tour stuck to a strict routine: Arrive in a small town; connect with local church leaders; present demos; hold classes to train agents (who would then use and sell the official Madam C.J. Walker line of products); then go on to the next town. Her Denver business, which she'd put in the hands of her daughter Lelia, became more focused on mail order, supporting these widespread "Walker Agents."

Walker's business took off. Within two years she was earning the equivalent of $150,000 a year in today's dollars. In 1910 Walker moved her operations to Indianapolis, working tirelessly to grow her company: creating her product, applying treatments, advertising, and reaching out to new markets. That same year, she incorporated the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company of Indiana, and owned all $10,000 worth of stock.

Philanthropist

It was around this time that Walker began her lifelong philanthropy, pledging $1,000 to a local YMCA. The Indianapolis Freeman proclaimed her the "first colored woman in United States history to give $1,000 to a colored YMCA building."

In 1912, after years of fruitless attempts to have an audience with Booker T. Washington, the African American educator and author, she finally interrupted a convention of the National Negro Business League — a group founded by Washington — to tell her story. Said Walker, "I have built my own factory on my own ground, 38 by 208 feet. I employ in that factory seven people, including a bookkeeper, a stenographer, a cook and a housegirl." Shortly after this event, Washington began inviting Walker to speak officially at his NNBL conventions. Their growing relationship helped them both: He recognized how Walker's inspirational story could help his school, and she coveted the advertising and editorial reach of the many black newspapers under Washington's control.

By 1913, Walker's business was earning $3,000 a month (over $50,000 in today's dollars). She put some of that money toward scholarships at Washington's Tuskegee Institute, where she had recently visited and been impressed by the students' work.

A major part of Walker's business plan was her assisting others. At a 1914 NNBL convention, Madam Walker stated, "I am not merely satisfied in making money for myself, for I am endeavoring to provide employment for hundreds of the women of my race." While here, Walker — ever the self-promoter — convinced the attendant delegates to officially proclaim her "the foremost business woman of our race."

And she was famous not only for her entrepreneurial skills and philanthropy; over the years, Walker had been climbing the social ladder too

Not one to rest on her accomplishments, Walker pushed forward, traveling to Jamaica, Haiti, Costa Rica, and Panama — in addition to both coasts of the U.S. — training ever more agents, and making arrangements to ship her products, since more markets meant greater profits for all of Madam C.J. Walker's enterprises.

And she was famous not only for her entrepreneurial skills and philanthropy; over the years, Walker had been climbing the social ladder too. At a time when overtly racist laws were still prevalent throughout the U.S., Walker had become known as "Indianapolis's premier black hostess," hosting dinner parties to entertain prominent members of the black community, both local and international.

In 1916 Walker moved to New York City to have easier access to the upper echelons of society, African American and otherwise. Her still-growing business was now bringing in the yearly equivalent of $1.5 million in today's dollars. Ads throughout the country touted "Walker's Scientific Scalp Treatment," stating that women could earn up to $40 a week using her sales and treatment methods, advancing the business-development portion of her strategy. (In comparison, $40 was a good monthly salary for African American women in other jobs they were likely to hold at that time.)

Social Advocate

Despite advances in some aspects of African American life at this time, including increased educational and business opportunities, the U.S. was still an extremely violent place for African Americans. Racially motivated murders and hangings by white mobs was an almost weekly occurrence. To combat these injustices, Walker began contributing to the NAACP's anti-lynching campaign.

It was with this backdrop that W.E.B. Dubois invited Madam C.J. Walker to attend a conference to discuss the "fundamental rights of the Negro." Walker was now part of the black elite. As such, she continued to further advance her agenda of greater opportunities for African American women. She organized the 200 agents in New York into the first chapter of the Madam C.J. Walker Benevolent Association, her plan being to pull all of her agents together into a large organization, controlled by African American women, with "political and civic objectives."

Legacy

Unfortunately, by 1917, Walker's breakneck pace was beginning to take its toll on her health, and she began suffering from overexertion, hypertension, and the beginnings of kidney disease.

Nonetheless, as a material display of her success, Walker at this time was also building Villa Lewaro, a 32-room mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson, in New York's Westchester County, home to the mansions of the Rockefellers, Tiffanys, Astors, Morgans, and Vanderbilts. In keeping with Walker's talent for omnipresent promotion, she had the house built near the street, rather than tucked away, to show off to others in the area. Walker was quoted as saying that she was building the mansion to "convince members of [my] race of the wealth of business possibilities within the race, to point to young Negroes what a lone woman accomplished and to inspire them to do big things." Unsurprisingly for the era, the New York Times noted a collective "gasp of astonishment" by the other citizens of this tony area that an African American woman would be moving in amongst them.

Despite her deteriorating health, Walker kept working. She was elected vice-president-at-large of the National Equal Rights League. She toured the Midwest, telling her story of success, expanding her business, and promoting the Circle for Negro War Relief, whose advisory board she had joined. She was determined to accomplish as much as possible.

On May 25, 1919, Madam C.J. Walker passed away. Her last words reportedly were, "I want to live to help my race."

There's some debate about whether Madam Walker, when she died, was the "first self-made female millionaire," as she is often called — her obituary in The New York Times stated simply that "estimates of Mrs. Walker's fortune had run up to $1,000,000" — but there's no questioning the fact that at the time of Walker's death, the Madam C.J. Walker company was bringing in over $3 million a year (in today's money), and had trained nearly 40,000 Walker agents since its inception in 1906. Madam C.J. Walker had proven herself a pioneer of the modern cosmetics industry; a master of marketing schemes, training opportunities, and distribution strategies; an early advocate for women's economic independence; and a groundbreaking philanthropist.

Related

For more on Madam C.J. Walker, see:

- On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker, by A'lelia Bundles, New York, NY: Washington Square Press, 2001.

- Designing for History: Madam C.J. Walker Estate. A look at Madam C.J. Walker's mansion in Irvington, New York.

Portrait of Madam C.J. Walker, ca. 1913. She marketed a number of successful cosmetic products. (Image courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives/A'Lelia Bundles.)