Next of Kiln: The Overbeck Sisters

The story of a group of sisters who were married to their art.

Jan 30, 2006

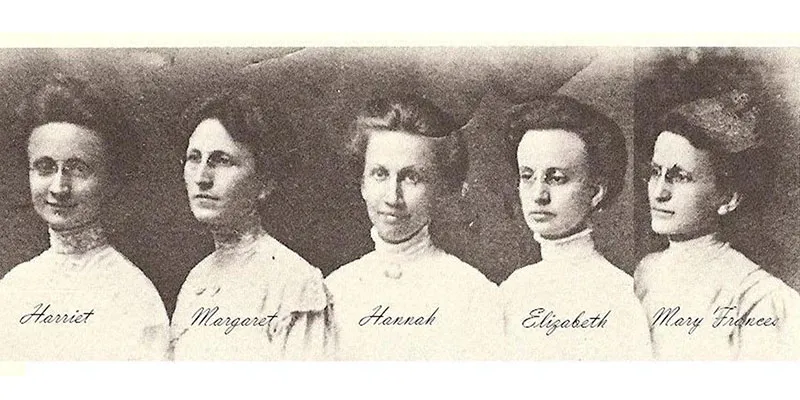

At the Houston ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, a woman brought in a small collection of pottery, including a bowl, a vase and some small figurines, which she said she had received from her aunt. Each of the pieces was made not by a single potter, but by a family of potters—five sisters, in fact—who worked under the same roof in Cambridge City, Indiana, during the early part of the 20th century. They were the Overbeck sisters—hard-working, unmarried women and sophisticated artists who worked as an ensemble to create some of the finest studio pottery ever to come out of Indiana.

"About 30 years ago, people finally realized these were more than mudpies," says Riley Humler, gallery director of Cincinnati Art Galleries. "Interest in Overbeck goes way beyond Indiana now. The people buying it are serious Arts and Crafts collectors all over the United States."

The Roadshow guest's collection includes a vase, a bowl, and some small figurines.

The sisters grew up in a farming family, but their home was imbued with the arts. Their father was a cabinetmaker and their mother knitted, stitched quilts, weaved rugs, and sewed lace. They grew up in a home built in the 1830s, reputedly the oldest in Cambridge City, which still stands, and all the daughters were educated. All four sisters were teachers at some point, and all but Elizabeth worked in other media, producing oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, and black-and-white drawings. They also produced the then-popular tie-dye fabrics, executed enamel on copper, decorated porcelain, and even made earrings, pins, and buckles. The pottery studio always included baskets of crochet, knitting projects, and delicate lacework.

The oldest daughter, Margaret, was a student at the Cincinnati Art Academy in 1892-93, and taught in Kentucky and Missouri before getting a teaching post at DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, where she taught drawing, watercolor, and china-painting from 1899 to 1910. She also taught art to her younger sisters Elizabeth and Mary. Margaret proposed that the sisters establish a pottery studio in their home, and although she died in 1911, the year the studio was launched, her sisters carried on her dream.

The four remaining sisters each took on specialties in their collaborative endeavor. Hannah and Mary Francis designed most of the pots. Elizabeth was the foremost potter, and experimented with glazes and clays. Harriet was a linguist who spoke French, German and Italian and was an accomplished musician. She said she didn't inherit skillful hands—what she called the "Overbeck Heritage"—but provided another essential role in the family business: she became her sisters' housekeeper.

The Overbecks eschewed a production-line approach: each piece of pottery was unique and handmade.

Quality, not Quantity

From the outset, the sisters' goal was to produce quality, not quantity. The women learned by trial-and-error and their workshop was simple, consisting of an electric potter's mill, a portable kiln fueled with coal oil, and a clay-sifter made by a handyman. Two principles guided them: that all borrowed art—such as motifs and designs from Europe or Japan—is dead art; and its corollary, that all good applied design is original. As part of the Arts and Crafts Movement, they often took their design motifs from nature, using plants, trees, birds, and animals indigenous to their Midwest environment. "Because of [our] freedom from hampering influences," Mary said later in life, "it would seem that whatever else an impartial judgment might find concerning the merits or demerits of Overbeck pottery, it would at least award it the distinction of being a thoroughly American product."

The Overbecks usually made functional pieces, such as teapots, pitchers and tea sets, and preferred simple shapes. They worked in both the Art Nouveau and then the Art Deco style. They made no production lines to maximize sales; each piece was unique and their output was modest. Only Elizabeth used the wheel; Hannah and Mary Francis did all of their pieces by hand. They experimented with their own glazes—they often used matt glazes and soft tones, although a robin's-egg blue became a trademark—and they kept their glazes secret. If a piece came out differently than planned, they destroyed it.

Elizabeth, Hannah and Mary rarely left their home, much less their town, but their work did. In the first few decades of operation, the Overbecks' ceramics were exhibited in Paris, Chicago, St. Louis, Baltimore, Detroit, and at the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, as well as Chicago's Century of Progress exhibit in 1933, and their pottery often was returned with prizes. Yet the women weren't recluses. Guestbooks that they kept showed they were visited by a stream of potters and other artists, groups such as the Indiana Artists' Club, journalists, educators, and even admirers and curious visitors from France, Germany, Poland, South America, England, and Scotland.

The Overbecks also made figurative pieces, often on commission. This little sculpture depicts a Fountain City, Indiana, man who was once a runaway slave.

The Overbecks also sculpted miniature figurines of people. Sometimes they would depict figures from history, such as George Washington. But they also took commissions to sculpt local figures, such as the runaway slave, a man from Fountain City, Indiana, who was depicted in one of the pieces that was part of the Houston collection. They also sculpted miniature animals and numerous pets, including dogs, cats, and birds, always coloring them true to nature, with none more than a few inches tall. The sisters, especially Mary, also sculpted what are referred to as "grotesques," caricatures of people and wildlife, and even fantastical creatures. They were first made as a way to test glazes, but grew into one of the sisters' steady sellers. Mary, who sculpted most of these pieces, called them "humor of the kiln."

Hannah died in 1931, and then Elizabeth in 1936, which led Harriet to observe, "the real light of the household has gone out." Harriett died in 1951, and Mary continued making pottery alone until she died in 1955. "One thing that adds to the value of their work today is that there aren't that many pieces out there," says Riley. "If you have a large piece of quality from their early period, you have something special."