Rare Portraits Survive Museum Blaze (In a Way)

How a 19th-century bureaucrat's bungling plan to get rich preserved hundreds of Indian portraits whose originals were lost to fire.

Mar 28, 2007

BY Ben Phelan

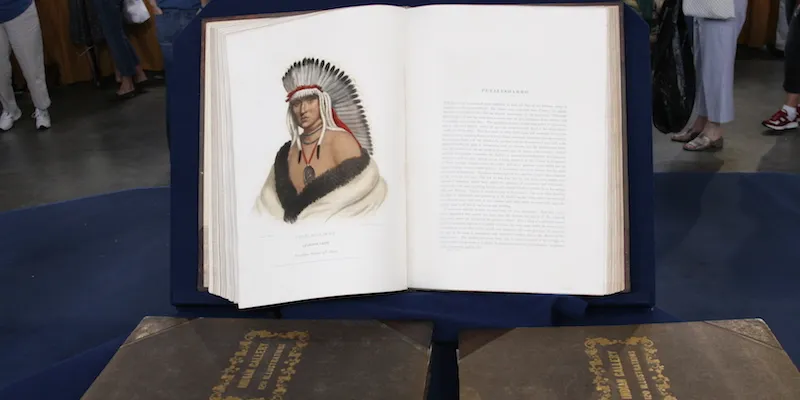

At the July 2006 Roadshow in Mobile, Alabama, Catherine Williamson of Bonhams & Butterfields appraised a well-preserved complete set of lithographs, entitled McKenney and Hall's History of the Tribes of North America, belonging to a guest named Thomas. Catherine placed the value of the set of three books at between $70,000 and $90,000. Undoubtedly, the large volumes filled with strikingly vivid portraits of 19th-century American Indians are authentic treasures, but why so valuable?

One Man's Plan for Portraits

In 1821, Thomas McKenney, the U.S. superintendent of Indian Trade, began commissioning portraits of American Indian leaders who traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate treaties with the federal government. McKenney would later express as his reason a desire to preserve "in the archives of the Government whatever of the aboriginal man can be rescued from the destruction which awaits his race." His opinion that American Indians ought to be "looked upon as human beings, having bodies and souls like ours" was, sadly, an enlightened view that few shared.

But his plan went forward, and for a few years, the ever-growing collection of portraits hung in McKenney's office—until a more entrepreneurial idea occurred to him: that of making money "beyond calculation" by commissioning lithographs of the paintings and selling them to the public in bound volumes, each portrait to be accompanied by a biographical sketch of the subject. It was the resulting series of three volumes that became known as McKenney and Hall's History of the Tribes of North America and offered for sale by subscription. Today it is widely acknowledged that the volumes contain some of the finest American lithography of the 19th century.

A History of Setbacks

The 15-year history of the books' publication is far too convoluted to give a full account of here; but in light of all the setbacks McKenney and his partners were dealt, it is nearly miraculous that any books were ever published at all. The story involves, among other things, McKenney's successful solicitation of former President John Quincy Adams as editor; many different publishers, some of whom went bankrupt, others cutting their losses and bailing out in the face of looming financial catastrophe; a deaf-mute genius lithographer whose company went bust; and endless crises of confidence and capital. Indeed, McKenney's own commitment to the project often wavered and would eventually expire.

Yet it is not that McKenney was feckless or inconstant; he just had no idea of how much money and work would have to be expended to realize his vision. At the same time, he is not without blame for some of the difficulties the project encountered. To remedy a particularly bad financial situation, and to rally his morale, McKenney secured as one of his string of financiers Judge James Hall of Cincinnati, and promised him access to a "very voluminous" amount of source material from which to write biographies of the paintings' Indian subjects. But when Hall moved to Philadelphia to set to work, he found no such material, and was also unable to coax McKenney into helping him. Hall spent the next eight years trying to track down many of the subjects, about whom all McKenney had provided was a name.

Moreover, it became clear several times that the price of the subscription—$120 for the whole set—was nowhere near enough to defray the costs incurred during the exacting production process. And the Economic Panic of 1837 nearly dealt the project a deathblow, depriving many of its subscribers of the means to pay for their subscriptions.

It was then that McKenney finally withdrew from the project completely. Hall and a new publisher brought the series to completion, with the final installment appearing in January of 1844, long after McKenney was inspired to make the remarkable series of portraits available to the public (and hoping to become a rich man in the bargain). In the end, there were 1,250 subscribers.

Fire at the Smithsonian

Enhancing the value of these rare books is yet another of the hardships that seemed to curse the project from its offing. In 1858, the original oil paintings that were subsequently lithographed for the bound set were moved into the "Castle" at the Smithsonian, the institution's first building and a repository for a great deal of artwork. But in the winter of 1865, workers who were relocating the Indian portraits brought in a wood-burning stove to keep themselves warm while they worked, and mistakenly vented the stovepipe into a ventilation shaft that they took for a flue. It took two weeks for the fire to ignite, but after it did, the roof of the Castle collapsed and the second floor was engulfed, along with 295 of the original Indian portraits. Only five paintings were rescued from the blaze. It remains the most catastrophic fire in the Smithsonian's history. Although one of the painters had made a few copies of his favorite portraits for himself, the great majority of the pictures would be irretrievably lost had McKenney, Hall, and their colleagues not finally persevered in their somewhat hapless lithography project.

But as is often the case when talking of value, it is the physical condition of Thomas' set of books that seems the most important consideration—more so even than the fraught history the volumes barely survived. "He had a lot of good stuff," Catherine Williamson said, "but I was really astonished at what great shape those books were in. The Deep South is generally not the best place for antiques. It's hot and humid, and books can get a lot of sun on them. So I don't know what he was doing to take care of those books, but he was doing the right thing."