Resources on Historical Maps, Colonialism and Indigenous People

An overview of informative resources about the political and cultural issues related to historical maps.

Mar 29, 2021

Originally published on: Mar 15, 2021

At the Spokane ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in August 2007, a guest named Maurice brought in a large and weathered-looking atlas, which he explained to appraiser Stephen Massey had passed down to him from his grandfather, who had acquired it in the 1950s. Embossed with the title "The Universal Atlas" in ornate gold lettering on the front cover, the volume was the work of renowned American cartographer David Burr.

A mapmaker, surveyor and topographer, Burr served in several official capacities for the United States government throughout the mid-1800s, including with the U.S. Postal Service, the House of Representatives, and the Senate.

Published around 1836, the atlas contains 63 different beautifully colored and well-preserved maps from every region of the world.

As ANTIQUES ROADSHOW experts regularly encounter and appraise old maps, especially from the 19th century and earlier, it's important to acknowledge a few key points about these historical documents. Maps are documents that reflect geographical and political circumstances as they exist at the time they are made, and also — crucially — the particular world view and built-in biases of those who commissioned and produced them. By and large, those people have been white Europeans and Americans of European heritage.

For example, as Massey pointed out, Burr's Universal Atlas depicts a map of Africa showing large areas of the continent practically featureless, indicating those regions were as yet "unexplored" by Europeans, and thus considered basically unpopulated, which of course they were not. But as Massey also mentioned, Burr's map foreshadows a period in the late 1800s, then still 50 years in the future, when the major European powers would eventually meet to negotiate and carve up the vast continent of Africa, and all its various indigenous inhabitants, to share out among themselves and rule over as colonial territories.

This process took place in 1884 and 1885 at the so-called Berlin Conference, convened by the German imperial chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, and was conceived as a way to avoid the warring among European powers themselves that was considered inevitable if the still "unclaimed" interior of Africa was not partitioned by diplomatic consensus. The political borders that still divide Africa today are direct results of these largely arbitrary and entirely self-serving decisions made by a relatively small number of men at the Berlin Conference; the political and cultural harm that has been borne by Africa's indigenous people since that time is incalculable.

Renaming of Indigenous Lands

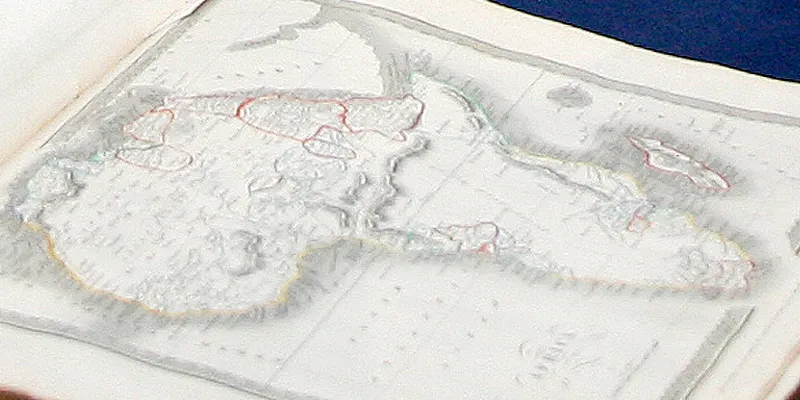

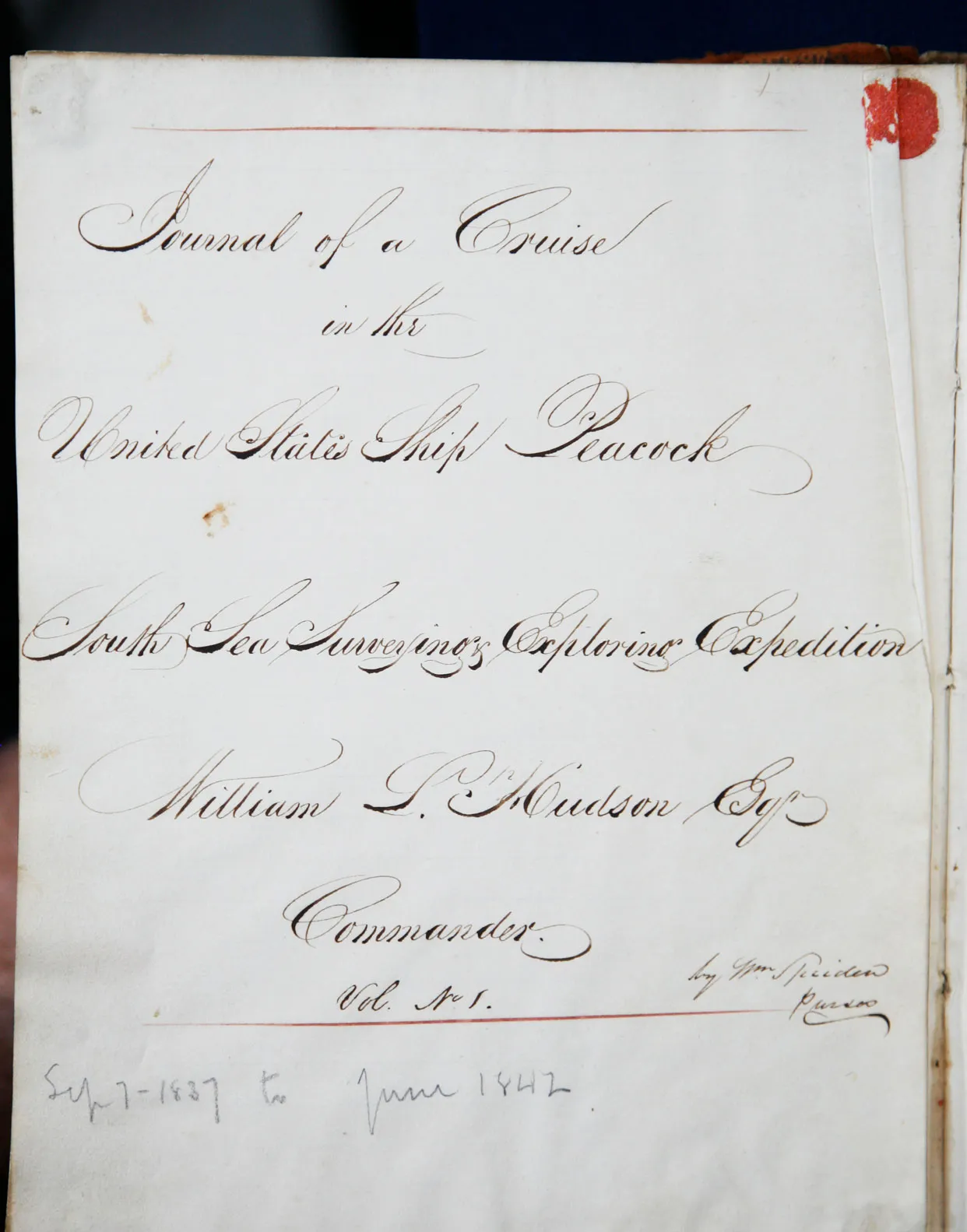

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s 2007 Louisville event, appraiser Tom Lecky encountered yet another record of similar cultural harms done to America's indigenous people, in the form of a pair of tattered journals brought in by a guest named Joseph. Joseph’s great-great-great-grandfather, William Spieden, had kept the journals while serving as ship’s purser aboard the U.S.S. Peacock during the so-called "Exploring Expedition" in the Pacific from 1838 to 1842, commanded by U.S. Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes.

Title page of the Exploring Expedition journal, which reads: "Journal of a Cruise in the United States Ship Peacock, South Sea, Surveying Exploring Expedition. William Hudson, Esq. Commander."

According to Lecky, the five-year maritime adventure Wilkes was appointed to command was “one of the largest exploring expeditions ever mounted by the United States and one of the first mounted by the United States Navy.” The primary aim of the expedition was to survey the Pacific Ocean for America's whaling and seal industries, and, as the secretary of the navy James Paulding put it, "to extend the bounds of science, and promote the acquisition of knowledge." Ultimately Wilkes's flotilla explored some 280 islands throughout the Pacific and even managed to chart 1,500 miles of the eastern coastline of Antarctica.

Lecky informed Joseph — to his seeming surprise — that while charting the Pacific Northwest, Wilkes named one of the small islands off the coast of Washington in honor of Joseph’s ancestor. Spieden Island is situated just south of Vancouver, in what is known as the San Juan Archipelago, which was named in 1791 by the Spanish explorer Francisco de Eliza after the Viceroy of Mexico, Juan Vincenta de Güemes Padilla Horcasitas y Aguayo. The indigenous people who originally inhabited the San Juan Islands were members of the Central Coast Salish Tribes and primarily included the Sooke, Saanich, Songhee, Lummi, Samish, and Semiahmoo.

European explorers’ renaming of islands and other indigenous territories was common at the time, part of the prevailing attitude that they were discovering territories previously unknown by European civilization, and thus could name them as they pleased — with little regard for how the native peoples may have identified those areas until then. During his time navigating the American Pacific Northwest, Charles Wilkes named many islands off the present-day coast of Washington to honor (or perhaps appease) various members of his crew, including William Henry McNeill (McNeil Island), J. L. Fox (Fox Island), Stephen W. Days (Days Island), and Alexander C. Andersen (Andersen Island).

Dividing up indigenous territory for colonial occupation is not the only way European and American powers have imposed their will on indigenous communities. In countless cases, the renaming of indigenous lands essentially erased the record of what native inhabitants had called those places for generations.

As Books & Manuscripts appraiser Ken Gloss commented in reference to other historical documents, it is vital to remember that what amounts to progress for some often means devastation for many others.

Similarly, during ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s 2021 visit to Sands Point Preserve on Long Island, a guest named John brought in a map that illustrated what is now New York in the 17th century, when it was settled by the Dutch and known as “New Amsterdam” or “Novi Belgii.” Prints & Posters appraiser Laura Ten Eyck, praised the map for including so much indigenous information, then pitying how most of it had been lost over time: “When the British started mapping the area, a lot of the names are…anglicized.”

The Dutch gained control of New Amsterdam in 1609 after Henry Hudson, who was hired by the Dutch East India Company to find a northwest passageway to India, came across the territory and claimed it for his employers. By 1624, the colony of New Netherland was established and grew to encompass all of present-day New York City and parts of Long Island, Connecticut, and New Jersey. Two years later, Dutch governor Peter Minuit formally purchased present-day Manhattan from the native inhabitants, who were called, Lenape, and spoke the Algonquin language of Munsee. Although there is no solid documentary evidence, several sources claim that Minuit got the natives to “agree to give up the island in exchange for trinkets valued at only $24.” In 1664, the Dutch lost New Amsterdam to the English, who renamed the territory after James, the Duke of York, who in 1685 would succeed his older brother as King James II.

New York City borough names and many of Manhattan’s popular street names originated from either British settlement or from the new Federalist government honoring the heroes of the American Revolution. For example, Queens, NY was [named after Queen Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II, and MacDougal Street, Greene Street, and Lafayette Street were named after Continental Congress member Alexander McDougall, General Nathanael Greene, and French military officer the Marquis de Lafayette, respectively.

Presently, the Lenape Center of Manhattan, lead by Lenape elders, is endlessly working to create programs, exhibitions, performances, workshops and more "to continue the Lenape presence."

During that same day in Sands Point Preserve on Long Island, Laura Ten Eyck met a guest named Pamela who brought in another map that illustrated a similar time in New York's history. Pamela's map featured Long Island in its early days, and Ten Eyck noted areas, such as Matinecock Point and Shinnecock, that were named for the indigenous people who inhabited the area. Pamela replied that the Dutch purchased a peninsula called Sint Sink from the Matinecock Indians, and it’s where her family lived at the time.

According to Matinecock Tribal Nation’s website, there are thirteen different tribes a part of the Algonquin community that dwelled on Long Island. The Matinecock tribe (Matinecock meaning “Hilly country) inhabited the northwestern area and were known to be excellent fisherman. With the arrival of the Dutch colonizers, they were the first to feel the impact of the foreigners, fleeing eastward after the massacre of the Iocal Indians in 1643. In 1789, the Flushing courthouse, which contained documentation of transactions with the Matinecocks, was destroyed in a fire, making it almost impossible for decedents of the Matinecocks to reclaim their ancestorial land.

In 1958, the Matinecock Indian Tribe was formally reactivated by a woman named Ann Harding Murdock (Princess Sun Tamo), and since then, the tribe has revived four of its ceremonies.

Loss of Tribal Land for Western Industrial Expansion

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s 2008 stop in Wichita, Kansas, a guest named Bruce brought in a timetable and map of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad from 1876, which he said he’d bought in an antique store in Oklahoma for $30 about 10 years prior. Prints & Posters appraiser Chris Lane noted that the document had an advertisement on the timetable side, placed by the railroad company, offering land for purchase.

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, also known as the Santa Fe Railway or AT&SF, was chartered in February 1859 to promote expansion and settlement in the southwestern United States, connecting the cities of Atchison and Topeka to Santa Fe. At that time, neither Kansas nor New Mexico had yet achieved statehood; Kansas became a state just two years later, in 1861, and New Mexico in 1912. The United States had acquired the Kansas Territory through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, and the New Mexico Territory in 1848 as a result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that ended the Mexican-American War.

The AT&SF was spearheaded by Cyrus K. Holliday, a capitalist with an interest in politics who sought to make a profit from the trade route along the Santa Fe Trail. A resident of Lawrence, Kansas, Holliday was also fairly active in the politics of his hometown and hoped that the railroad would be a selling point for the Kansas Territory to become part of the Union. After several financial setbacks, in 1863, with the help of Kansas Senator Samuel Pomery, the AT&SF was included in the Pacific Railroad Act of 1863. As a provision of the new law, Congress awarded land grants to the AT&SF, some of which the railroad company sold off to help with funding, as seen in the advertisement on Bruce’s timetable.

Despite the land grants from Congress, the AT&SF continued to acquire land for the railroad, oftentimes at a devastating cost to the local Native American tribes living in the region. Prior to the land grants offered to the AT&SF, the federal government and the Potawatomi Tribe had signed the Kansas Treaty of 1861, which “divided the Tribe’s reservation into allotments and outlined a rough path to becoming an American citizen.”

The Potawatomi people saw this treaty as a threat, however; an ultimatum either to surrender ownership of their land or be forced to relocate their tribe once again. As a result of the treaty, two-thirds of the tribe became the Citizen Potawatomi, dividing the land into allotments for individual families and giving up the traditional way of communal habitation. The remaining one-third chose to continue to live on the communal land and became the Prairie Band. Several years later, through the Treaty of 1867, the Prairie Band was displaced once again as their communal land was purchased by the railroad company from the government for $150,000 — a sum that did not even include funds for the Prairie Band's relocation.

Some 700 miles to the west, the Pueblo tribes of New Mexico also suffered due to the expansion of the Santa Fe Railroad. The Pueblo people had already suffered from Spanish colonization beginning in the 16th century, and with the arrival of the AT&SF, the Pueblo again endured disruptions to their traditional way of life through the loss of fertile farming land and water rights. In his 2015 book The Railroad and the Pueblo Indians, author Richard Frost, an emeritus professor of American history and Native American studies at Colgate University, notes how some Pueblos tried to embrace some of the changes brought this industrial expansion, but the benefits were limited, slow in coming, and came largely at the cost of their cherished traditions.

Selected Resources for Further Learning

For those interested in finding more information about historical maps, and the cultural and political topics related to them, ANTIQUES ROADSHOW recommends the following resources.

The Colonization of Africa, 1870 - 1910

“A map showing the European colonization of the African continent before and after the Berlin Conference of 1885, when the most powerful countries in Europe at the time convened to make their territorial claims on Africa and establish their colonial borders at the start of the New Imperialism period.”Colonial Presence in Africa

"At the Congress of Berlin in 1884, 15 European powers divided Africa among them. By 1914, these imperial powers had fully colonized the continent, exploiting its people and resources."The Partition of Africa

An overview of the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 and the colonial partitioning of Africa by European powers that resulted.Native Land

An interactive map that allows users to see the original borders of Indigenous territories that existed prior to colonization.Decolonial Mapmaking | Reclaiming Indigenous Places and Knowledge

An in-depth look into how the renaming of colonized lands by settlers has stripped away the heritage of the Indigenous people who once lived there, and how the modern names erase the Indigenous cultural knowledge of the land.Reclaiming Indigenous Place Names

How Yellowhead Institute — a First Nations-led research center based in the Faculty of Arts at Ryerson University in Toronto, Ontario — is pursuing justice for indigenous communities by fighting to restore land and place names.Wilkes, Charles (1798-1877)

A brief overview of Lieutenant Charles Wilkes's expedition, his policy on natives, and his desire to rename charted territory.United States Exploring Expedition (1838 - 1842)

From Oregon Encyclopedia, a curation of educational resources on Charles Wilkes's Exploring Expedition.Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

An educational resource center within the Boston Public Library that seeks to foster geographic perspectives on the relationships between people and places, and whose digital collection includes over 10,000 historic maps.Maps in Colonialism

An overview of the transformation of maps and map-making techniques to fit the shifting needs of European colonizers and how those transformations have developed the maps we know today.The Power of Colonial Maps

An educational resource offered by the School of History at the University of St Andrews, which details examples of how a colonial map can influence the socio-cultural-political perspectives of the reader.How Cartography Helped Make Colonial Empires

An introduction to the exhibit "Defining Lines: Cartography in the Age of Empire" at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University from September 2013 to January 2014, co-curated by Duke University professors. The exhibit illustrates the implications of colonial cartography that serves the political agendas of Western governments.A Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

A guide on how to craft and write an Indigenous Land Acknowledgement Statement from the Native Governance Center, a Native-led nonprofit organization that serves Native nations in Mni Sota Makoce, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

*Lenape Center Lenape Center has the mission of continuing Lenapehoking, the Lenape homeland through community, culture, and the arts.

- How New York Was Named For centuries, settlers pushed Natives off the land. But they continued to use indigenous language to name, describe, and anoint the world around them.