So, Whose Pistol Is This?

In the early 20th century, this Merwin-Hulbert revolver was evidence in a Wisconsin murder trial. Now, the judge's grandson owns it. Find out why.

Jan 11, 2007

BY Ben Phelan

Knowing the story of an antique is at least half the fun of owning it. The provenance that led to an object's coming to rest with its owner can be intricate and unexpected in its detours. And of course there can be monetary benefits to such knowledge: if you can account for an object's history with documentation, such as photographs or bills of sale, you can assure a prospective buyer of the item's authenticity, and thereby secure a better price. But for most of us, not looking to turn a profit, the story of our heirlooms, over time, intertwines with our own and that of our family and friends. And we are as reluctant to part with it as with them.

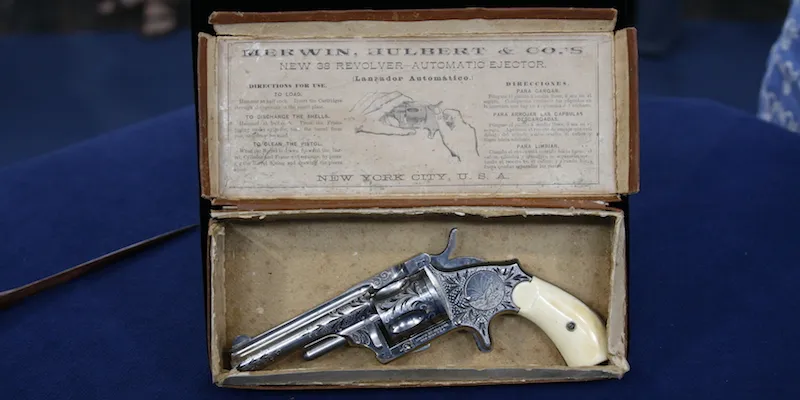

Since the 1920s the family of Chuck Totto, who was a guest at the Honolulu Roadshow, has been in possession of a fine Merwin-Hulbert pistol. Martial applications aside, its impressive craftsmanship is attested by the elaborate hand-tooled engravings that run the length of the weapon and the ivory handle whose patina has mellowed over the years to a milky-gold. Chuck didn't know that most Merwin-Hulberts were pretty plain—unadorned gun metal with black rubber handles; so his estimate of its worth, $1,500, didn't take into account the weapon's uniqueness. He was surprised and thrilled when appraiser Paul Carella came up with a value of $3,000 to $5,000.

But before bringing it to the Roadshow, Chuck, who is a lawyer, double-checked with his sister that his recollection of the piece's origins was accurate.

"We both heard the same story from my mom," he told us recently, "and she was a pretty straight shooter. She didn't embellish family stories any more than the average mom, I don't guess."

Totto family lore has it that Chuck's grandfather, Claude Z. Luse, who was a federal judge appointed by President Warren G. Harding during the Prohibition period, came across the pistol while trying a murder case in Wisconsin.

"Back then there was a lot of bootlegging going on, and the Al Capone folks who were operating out of Chicago used to run things through Wisconsin quite a bit," Chuck recounted. "So a lot of the criminal cases dealt with bootlegging. One of the bootleggers ended up shooting somebody, and Grandpa Luse liked the pistol so much he decided to hold on to it."

"I don't think they were as careful with evidence lockers as they are now," he added.

We asked him if he was concerned that the government, or even the murderer's descendants, might have a legal claim on the pistol today.

Chuck said he hopes that at this point the pistol has been in his family for long enough that no one would bother to challenge his possession of it. "I hope the government wouldn't be interested in having the pistol returned. But if they did, I guess I'd have to ask them to show me some identification."

And Chuck's attachment to the pistol has grown over the years. "When I was a kid I was just like, 'Wow, it's a gun!' But as an adult I look at the craftsmanship. And as you get older these things mean different things to you. My uncle died in World War II, my parents died when I was in my early 20s, and one of my two sisters has passed away. So when I see this, it helps me connect, physically, with my old home, where I grew up, and the things that were the permanent backdrop of my old environment. It means a lot to me, but my son's generation might feel less connected to it, too far removed for it to be of much personal value." Then, chuckling, he joked, "I'll try to beat it into them."

"Discovering all that kind of stuff—like my dad's old RAF uniform—was just fascinating to me as a kid. But the connection is different at my age. Even if the value were 10 times what it was appraised at, I'd hold on to it."

Ten times, Chuck?

"Well, 10 times... I'd have to think about it."

Chuck still has the pistol's original box, the top of which bears "Directions for Use."