The History and Legacy Surrounding "The Well of Loneliness," the First Lesbian Novel to Be Published in the United States and Britain

During the summer of 1928, British author Radclyffe Hall published a semi-autobiographical novel about a lesbian relationship, bringing the subject of homosexuality into the country’s literary culture. While lesbianism was not considered illegal at the time, the book was deemed illegal for violating the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, and was quickly removed from circulation.

Apr 1, 2019

During ANTIQUES ROADSHOW’s May 2018 visit to Hotel del Coronado, a guest named Mike brought in a novel that had been given to him by his late sister. Published in 1928, The Well of Loneliness, by British author Radclyffe Hall, was a sensation at the time for its depiction of a lesbian relationship. Its author, known to her close family and friends as “John,” was an open lesbian, which, despite being legal, was still considered immoral in early-20th-century British society. The book caused a stir among readers in England, and its morality was publicly called to question by Sunday Express editor James Douglass, who claimed it had the power to “corrupt” young people and society:

In order to prevent contamination and corruption of English fiction, it is the duty of the critic to make it impossible for any other novelist to repeat this outrage. I saw deliberately that this novel is not fit to be sold by any bookseller or to be borrowed from any library.

Hall’s publisher, Jonathan Cape, was charged under the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, the same law that had sent author Oscar Wilde to prison in the 1890s. In November 1928, a British magistrate, Sir Chartres Biron, found The Well of Loneliness to be obscene and ruled that the novel should be taken out of circulation and "destroyed."

Early Life and Influence

Marguerite Radclyffe Hall was born on August 12, 1880, in Hampshire, England, to a wealthy family. She grew up without forming lasting relationships, and as an adult pursued the affection of married women. While visiting Germany in 1907, Hall met and fell in love with Mabel Batten, a 51-year-old married woman with a daughter and grandchildren. Readers of The Well can find comparisons between Hall’s personal life and the life of the book’s heroine, Stephen Gordon, a female character who falls in love with a much older, married woman. Batten, whom Hall later left when she fell in love with Batten’s cousin, gave Hall the nickname "John," which the writer used for the rest of her life.

Hall drew much of her inspiration for The Well from the writings of the English sexologist Havelock Ellis. Throughout her life, Hall described herself as a “congenital invert,” which was a term taken from sexology and is derived from the idea of “sexual inversion,” referring to those who “believed their gender role was opposite to their biological sex.” According to sexologists, females who experience sexual inversion are described as possessing a masculine identity but living in a female body. The Well highlights the ideas of sexologists through the characterization of Stephen Gordon, a female who longs to be accepted as a male among her peers and lovers. In the final lines of the book, Stephen cries out to God and the world to accept “the invert.”

The Trial in Britain

In the Spring of 1928, Hall — who was already a successful published poet — approached her publisher, Jonathan Cape, with a manuscript that she claimed would be "taking a great personal and cultural risk." Hall intended on creating a novel that would “speak on behalf of a misunderstood and misjudged minority,” and wrote a coming-of-age story about a lesbian’s journey in discovering her identity and place in society. On August 19, 1928, just one month after The Well’s publication, James Douglass of the Sunday Express wrote an article calling for the immediate eradication of the book. Douglass’s arguments rose to the attention of the home secretary, who publicly deemed the book “obscene.” In response, Cape did cease publication of the book in Britain; the publisher subleased the novel to the French firm Pegasus Press, however, and new editions were printed in France, albeit without Hall's permission.

Towards the beginning of October 1928, several weeks after republication in France, the books were seized by British customs officials, who claimed Cape was violating the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which defined a book as obscene if it “tended to corrupt those whose minds were ‘open to immoral influence.’” Eager to fight the charge, Cape called upon 160 potential witnesses who would be willing to stand against the book’s censorship, including Virginia Woolf, George Bernard Shaw, and T.S. Eliot. The outreach proved unhelpful, however, as many writers were keen to distance themselves from the trial and did not want to damage their reputation for a book that was considered, by some, to be lacking literary value. In a letter to her nephew, Virginia Woolf called out the cowardice of her colleagues:

Most of our friends are trying to evade the witness box; for reasons as you may guess. But they generally put it down to the weak heart of a father, or a cousin who is about to have twins.

On November 16, 1928, Biron ruled that the novel was in fact obscene and ordered its immediate removal from circulation. Despite the book's lack of explicit sexual imagery — as well as the fact that it was perfectly legal to be a lesbian in Britain — Biron claimed that the true test of obscenity was based on whether the subject matter had the tendency to corrupt.

...the book is presented as a tragedy ... [that] people who indulge in these vices are not tolerated by decent people; they are not received in society and they are ostracized. There is not a single word from beginning to end of this book which suggests that anyone with these tendencies is in the least blameworthy ... all characters in this book who indulge in these vices are presented to us as attractive people and put forward for our admiration; and those who object to these vices are sneered at in the book as prejudiced, foolish, and cruel!

Since the book sympathized with rather than condemned these characters, Biron stated that The Well did indeed corrupt. Cape and Hall had lost their battle in Britain, and the topic of sexual inversion would remain a taboo in British culture.

The Well Comes to America

Across the Atlantic, the news of The Well had spread to publishers in the United States, many of whom were eager to buy the rights to the book. After The Well had been unofficially labeled “obscene” by the British home secretary, a New York City publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, expressed interest in buying the rights to the book to be produced in America. Yet, due to the legal and public relations battle associated with the story, Knopf eventually withdrew.

By November 1928, Pascal “Pat” Covici and Donald Friede — who had created their own publishing firm just five months prior — scraped together the money to buy the rights to Hall’s novel. Despite both men having experience handling sensitive material within the publishing industry, they hired Morris Ernst to assist with legal issues against the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), which dedicated itself to supervising public morality. Prior to taking on The Well, Ernst had practiced law for 13 years and had recently defended similar charges of obscenity in literature.

In preparation for his defense, Ernst researched the themes in sexology that Hall drew inspiration from. It was significant to Ernst to distinguish between sexual inversion, which pertained to a person’s gender role, and homosexuality, which focuses on a person’s sexual desire. Ernst chose to separate the two concepts by categorizing inverts, like the character of Stephen Gordon, as “thwarted in life” or “not fully developed” as opposed to “homosexual," which he categorized as an involuntary condition rather than a choice.

Ernst took his case a step further by comparing the language of The Well to the language of Mademoiselle de Maupin, a novel by the French author Théophile Gautier, which was taken to trial in 1922 for its depiction of a lesbian prostitute, yet was deemed appropriate — a major loss for the NYSSV. Ernst compared the explicit language presented in Mademoiselle to the more discreet language in The Well, noting that Hall’s book was considerably better written and held important social significance. Countering claims that the novel was a corrupting influence, Ernst noted that the book was not only sold at a higher price than the average novel — five dollars compared to the typical two dollars and fifty cents, making it more difficult for the middle class to afford it — but that it was “a lengthy, closely printed book without illustrations,” and believed that those of vulnerable moral character, who would be easily corrupted, would be less likely to pick up a copy.

On April 19, 1929, the Court of Special Sessions in New York City declared that The Well was not obscene. The court agreed that “the book in question deals with a delicate social problem, which, in itself, cannot be said to be in violation of the law unless it is written in such a manner as to make it obscene. …”

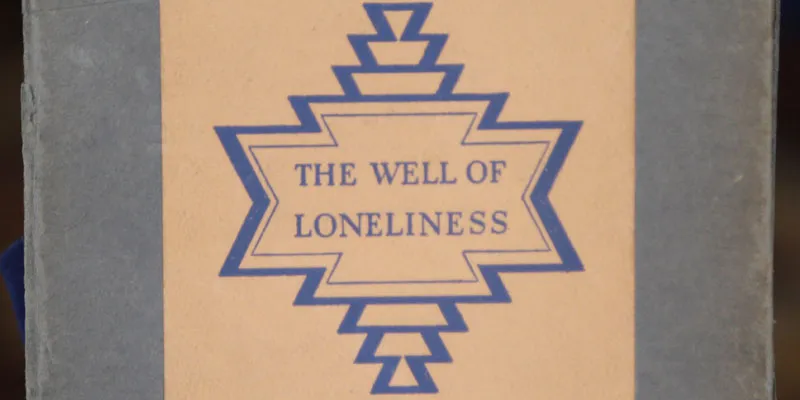

That same year, in honor of the court’s decision, Covici-Friede published a special deluxe limited “victory edition” of the book, a two-volume copy, printed with Ernst’s summary of the trial, and Hall’s autograph. And this is the very same special edition of The Well that Mike shared with appraiser Catherine Williamson at the San Diego ROADSHOW in May 2018. Number 43 out of only 225 copies published, as Williamson pointed out, with Hall's signature on the slip case.

Noting that the volume would likely sell at auction for $1,000 to $1,500 today, she called it "a landmark book in gay and lesbian modern literature of the 20th century."

Related

To learn more about Radclyffe Hall and The Well's journey towards universal publication, visit:

Defending The Well of Loneliness

A behind the scenes look at the controversy surrounding the publication of The Well of Loneliness.November 9, 1928: The Trial of Radclyffe Hall and Virginia Woolf's Exquisite Case for Freedom of Speech

A depiction of Virginia Woolf's efforts to defend The Well of Loneliness.Banned Books Week: The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

Summary of the novel's fight in both the British and American court systems."I Made Up My Mind to Get It": The American Trial of The Well of Loneliness, New York City, 1928-29

From the "Journal of the History of Sexuality," an in-depth look at The Well's trail in America written by Leslie A. Taylor.Unfolding the Court Case That Banned a 1920s Lesbian Novel

Listen to a podcast that explains the reasoning behind the British court's decision to label the book "obscene."