The Legend of Zelda (Sayre Fitzgerald)

More on the creative yet troubled Jazz Age life of Zelda Fitzgerald and the heartbreaking result of her marriage to writer F. Scott Fitzgerald.

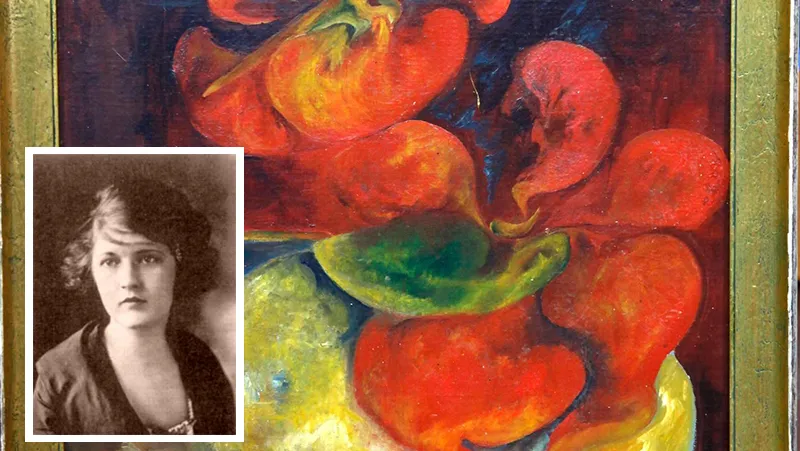

Zelda Sayre (inset), around age 17. According to appraiser Kathleen Harwood, she made this oil painting of nasturtiums about 1935, at the age of 35. (Image of Zelda Sayre: Wikipedia.com)

Mar 26, 2012

BY Ben Phelan

Well before she met F. Scott Fitzgerald and became an embodiment of Jazz Age glamour and dissipation, Zelda Sayre was an icon in her hometown. In the genteel milieu of upper-class Montgomery, Alabama, the teenaged Zelda smoked cigarettes, spent more time with boys than was thought proper, danced naked in the lily pond, and generally attracted so much attention that a fraternity sprang up at Auburn University, Zeta Sigma, whose pledges swore an oath of devotion to her. The fraternity was not really serious, nor was it really a joke; Zelda was, by all accounts, the pre-eminent belle of Montgomery.

Over the course of a life with Fitzgerald that was marked by glittering wealth, institutionalization, days-long parties and attempts at suicide, Sayre would try writing and dancing, but would leave her most lasting legacy in a body of paintings, most of which were created while she was a psychiatric patient at sanatoriums in Europe and the United States.

This oil painting of nasturtiums, passed down from one of Sayre's psychiatrists, was brought to the El Paso ROADSHOW in July 2011, where Kathleen Harwood appraised it for between $10,000 and $20,000.

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda Sayre met in Montgomery in 1918. He was a 21-year-old Army officer stationed temporarily in Camp Sheridan; she was 17 and just out of high school. To welcome the GIs, such as Fitzgerald, who were shortly to be shipping out to fight in the Great War, Montgomery's country club organized community dances. Sayre performed a solo dance and Fitzgerald, smitten, immediately began courting her.

Fitzgerald was spared deployment by the Armistice and moved to New York, where he worked in advertising and began exchanging letters with Sayre. Fitzgerald was an obsessive correspondent, often comparing Sayre to a princess in a tower. "Scott," she replied, "you've been so sweet about writing—but I'm so damned tired of being told that you 'used to wonder why they kept princesses in towers' — you've written that verbatim, in your last six letters!"

Which Side of Paradise?

In 1919, Fitzgerald sold his first novel, This Side of Paradise. a successful author with bright prospects, he returned to Montgomery to renew his courtship. The couple had a pregnancy scare; Sayre quickly decided to accept Fitzgerald's proposal and marry. The couple honeymooned in New York, where their youth and vibrancy, fueled by colossal alcohol benders (Fitzgerald was already an alcoholic), made a powerful impression upon a city that was buttoned-down and class-conscious. Dorothy Parker, seeing the couple riding on top of a cab down Fifth Avenue, wrote, "They did both look as though they had just stepped out of the sun. Their youth was striking. Everyone wanted to meet them."

Fitzgerald was not prepared for how modern and unlike a princess in a tower Sayre was, nor was she prepared for the seclusion Fitzgerald would demand in order to fulfill his ambitions. Sayre hoped her proximity to a famous writer would help her to find an outlet for her creative impulses. She was, to an unknown extent, a collaborator on Fitzgerald's fiction. But Fitzgerald generally discouraged his wife from pursuing a creative life— in part so he alone could cannibalize her diaries for dialogue.

Despite Fitzgerald's long shadow, Sayre sold a number of articles and stories to magazines—some of which were published with a joint by-line, or as Fitzgerald's alone — including a pert review of Fitzgerald's second novel, 1922's The Beautiful and Damned." It reminds me in its more soggy moments of the essays I used to get up in school at the last minute by looking up strange names in the Encyclopaedia Britannica," Sayre wrote. "It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage ... [p]lagiarism begins at home."

In 1924, the couple moved to Paris, soon relocating to the French Riviera. While working on The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald largely ignored Sayre; she met a French pilot and asked for a divorce. In response, Fitzgerald locked her up in the house. Fitzgerald's alcoholism grew more serious and Sayre's behavior became erratic. Once, Fitzgerald came home blind drunk and smashed a vase; Sayre objected; Fitzgerald punched her in the face. He was often too drunk to work. Each suspected the other of homosexuality. Fitzgerald blamed Sayre for his problems and placed strict controls on her comings and goings. Sayre's mental health, never robust, began to deteriorate more quickly, and she overdosed on sleeping pills.

With her youth disappearing, at 27, Sayre fixated upon ballet, which she'd taken classes in as a girl. She was too old to become a star, but after years of compulsive practice, which made her nerves and body frail and ragged, she'd advanced enough to be offered a solo in an Italian production of Aida, a role which could have led to a professional career. For unknown reasons, Sayre declined the offer. Shortly thereafter, while in a car driven by Fitzgerald, she seized the wheel and tried to force the car off a cliff.

Institutionalization and Painting

In 1930, Sayre checked herself into a sanatorium just outside of Paris, where she was diagnosed, probably incorrectly, as schizophrenic. (Schizophrenia was a brand-new and much overused diagnosis.) She soon transferred to a second, then a third hospital. "It's dreadful," she wrote, "it's horrible, what's to become of me, I must work and I won't be able to, I should die, but I must work. I'll never be cured." Nonetheless, Sayre recovered somewhat and checked out. Once she was back with Fitzgerald, she soon had another breakdown. When Sayre was admitted to a clinic at Johns Hopkins, in Baltimore, her doctor found no signs of a mental illness, only a destructive relationship with a paranoid, alcoholic husband.

While at Johns Hopkins, Sayre wrote her only novel, Save Me the Waltz, which was published by Scribner in 1932 over Fitzgerald's initially strident, horrified objections. He feared the harm the autobiographical book would do to his reputation, and resented her use of their lives as material, a resource he considered his sole property. Sayre hadn't shown her husband the manuscript. "I did not want a scathing criticism such as you have mercilessly — if for my own good — given my last stories, poor things. I have had enough discouragement." In the end, Fitzgerald helped Sayre edit the draft, imposing some of his changes by force of will. Though Sayre was unaware of it, her contract stipulated that 50 percent of the book's proceeds would go toward paying down her husband's debt with Scribner. (The book was a flop, making the clause moot.)

Sayre was undoubtedly mentally ill, though at this late date it is impossible to say how much of her illness was caused by circumstance and how much was of an organic origin. Biographers have plausibly speculated that she may have been bipolar. In any case, once Sayre entered the mental health system of the 1930s, she would never permanently leave it. She was subjected to all manner of primitive treatments: powerful tranquilizing drugs, brutal rounds of electroshock that erased much of her memory, and "insulin shock" treatment, in which coma was induced by repeated, massive injections of insulin.

It was in this unhappy period that Sayre did most of her painting and found her style, which was clearly influenced by the romantic prints of Toulouse-Lautrec, the stark lyricism of Georgia O'Keeffe and Pablo Picasso. She was not without a sense of experimentation and attempted, she wrote her daughter, Scottie, "to achieve all color values by the juxtaposition of red, blue and yellow."

By the time of Fitzgerald's death from a heart attack, in 1940, Sayre and he had scant contact. She claimed to have little memory of the 1920s, a result of the shock treatments she had endured. A fire in 1933 destroyed many of Sayre's paintings. Sayre herself, along with her sister, destroyed an unknown number of additional canvases, and donated others to be painted over by art students. In 1948, while Sayre was a patient at the Highland Mental Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, she was killed in a fire.

From the time Sayre had married Fitzgerald, she was perhaps doomed to live in his shadow; she felt painfully the controls imposed upon her by a domineering, jealous, alcoholic husband, and never fully developed her creative potential. But amid the turmoil of Sayre's life with Fitzgerald, including nearly 20 years spent in and out of sanatoriums, she did produce a modest legacy: a novel, a handful of magazine articles and stories, an uncertain role as collaborator on her husband's books, and a number of paintings, including this somber, 1935 oil-painting of nasturtiums, appraised at between $10,000 and $20,000.

Had Zelda Sayre been born a few decades later, she would have found the world more welcoming to independent and creative women. And her brilliant husband might have found it easier to support and encourage her.

Oil on canvas of nasturtiums, which Kathleen Harwood attributed to Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, ca. 1935, and appraised for between $10,000 and $20,000.