The Pine Bluff Student Sit-ins of 1963

Learn more about Arkansas student sit-ins at the Pine Bluff Woolworth's lunch counter in 1963.

Mar 26, 2018

BY Ben Phelan

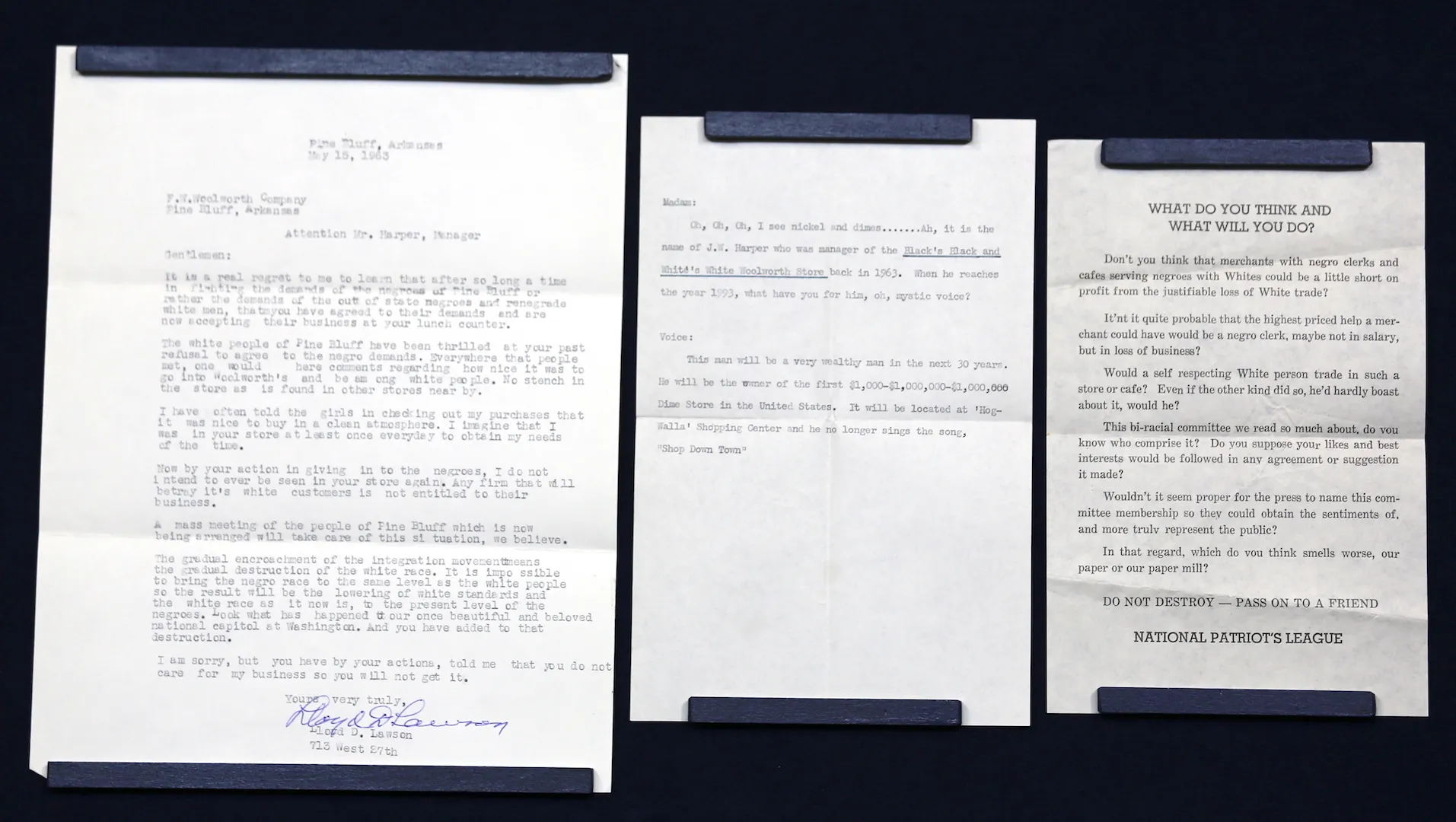

At the July 2017 St. Louis ROADSHOW, a guest brought in a small collection of typewritten documents, handed down to her from her father, which he received while managing a Woolworth’s department store in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in 1963. In the few years prior, civil rights activists had already conducted sit-ins at Woolworth’s department stores in Greensboro and Durham, North Carolina, in protest against the racial segregation that prevailed at Woolworth’s lunch counters, and indeed across the South.

The import of these documents [see them below], written by anti-integration whites, was clear: Uphold segregation … or else. And though the Pine Bluff sit-ins were not as prominent in the news as those in Greensboro, for example, they were no less dramatic. The seeds of the sit-ins had been sown five years before, in 1958, when the chancellor of the historically black Agricultural, Mechanical & Normal College, in Pine Bluff, invited Martin Luther King Jr. to address the graduating class.

Arkansas AM&N was a “largely self-sufficient” land-grant college, as the historian Holly Y. McGee has written in The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, and Pine Bluff’s black community was “large and vigorous,” “educated [and] affluent”; but chancellor Lawrence Davis’s decision was a bold one nonetheless. The Civil Rights movement had barely begun and was off to a queasy start. In the previous year, the state capital, Little Rock, had been roiled when nine black teenagers asserted their constitutional right to public education by attempting to enter Little Rock Central High School.

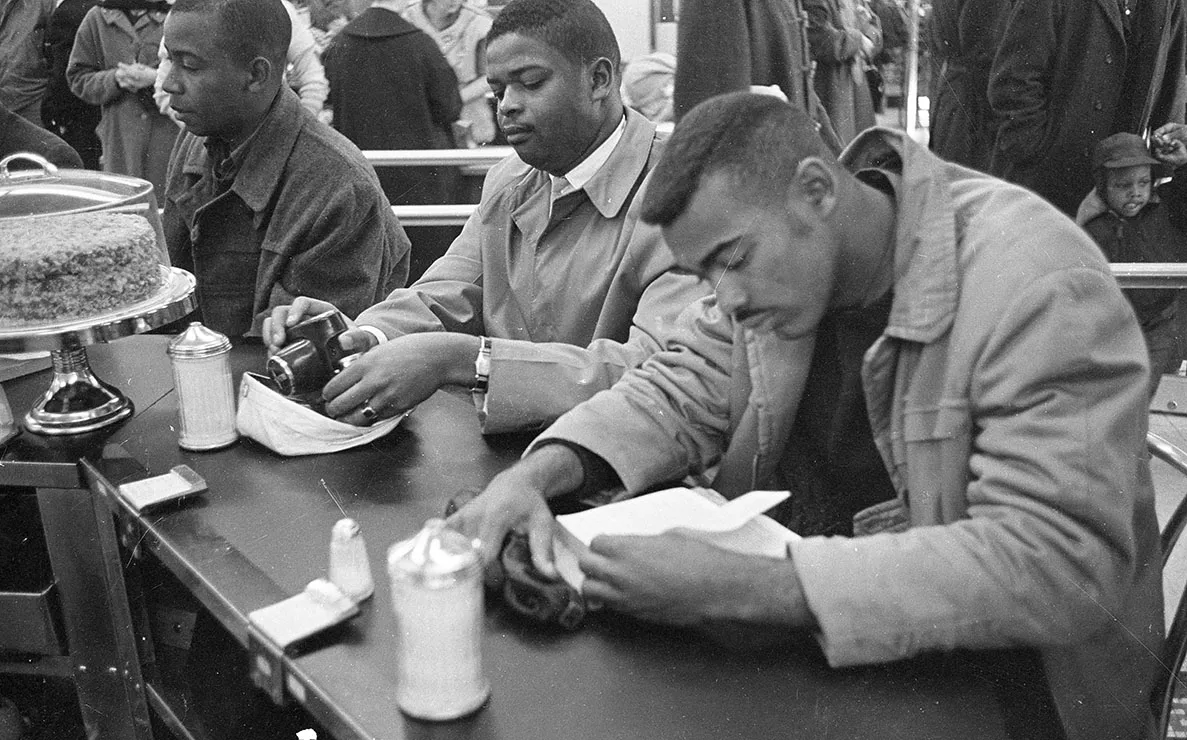

Civil Rights protesters at Woolworth's lunch counter sit-in, Durham, North Carolina, February 10, 1960. (Image source: Wikimedia Commons/News Negative Collection, State Archives of North Carolina).

In response to the teenagers’ temerity, Arkansas governor Orval Faubus ordered the state’s National Guard to occupy the school, which in turn prompted President Eisenhower to take over command of the state force and then order the U.S. Army to ensure the children’s entry to the school. At the end of the 1958 school year, Governor Faubus would close the public school system entirely rather than allow black Arkansans equal access to public education.

In such a fraught, tense environment, Chancellor Davis found the courage to invite the instigator-in-chief and emerging leader of a radical movement, to address his students. Martin Luther King delivered a fiery message: "Go home determined to revolt against segregation and discrimination everywhere." Chancellor Davis posed for a photo with King. And yet, five years later, as students energized by King's message of nonviolent resistance themselves found the courage to act, staging a series of sit-ins at a local lunch counter, Chancellor Davis suspended, then expelled, them. What had changed?

Pine Bluff, whose population was upward of 40,000 at the time, was 45 minutes from the capital in Little Rock. "By early 1963," as McGee writes, "news of [the] recent civil rights gains in Little Rock" had spread to Pine Bluff. Many students, she goes on, had been waiting for an opportunity to join the movement; the progress achieved in Little Rock provided the impetus.

Sit-ins at the Woolworth Lunch Counter

In the early afternoon of February 1, 1963, 13 black AM&N students sat down at the Woolworth lunch counter and asked for service. A waitress instead turned off the lights. For three hours, the students sat in darkness. At closing time, they left. The next day — and for days after that — they returned, and as they did, their numbers grew.

After a week and a half, all of Pine Bluff, black and white, had learned of the sit-ins. At this point, Chancellor Davis did two things more or less simultaneously. One, he met with a protesting student and told her that he was adamantly committed to their cause, and would quit his job rather than discipline her or her comrades. Two, he wrote an open letter threatening suspension for any student who participated in a sit-in.

As he told the local paper, "All students who plan to participate in sit-in demonstrations … are requested to withdraw from the college." Those who did not self-expel, he went on, would be immediately suspended. When the protestors carried on in their nonviolent action, Davis made good on his threat, suspending and ultimately expelling 15 of his students.

"The thing that was so tragic for most of us was that we loved this man," a student leader named Joanna Edwards later said. "We just loved him to death."

Chancellor Davis made his paradoxical choice, punishing students for actions he privately lauded, for the same reason that the protestors were sitting in at the lunch counter: He was not free either. In 1958, after Martin Luther King had spoken at AM&N at his invitation, Davis traveled to the capitol to secure the college's funding in the state budget.

Once there, he was lectured, bullied and demeaned by a state legislator for supporting the voluble civil-rights leader. "You double-crossed us!" the legislator told him, a painful accusation that carried the subtext that Chancellor Davis and he were on the same side — even though not a single African American would serve in the Arkansas legislature between 1893 and 1973 — but only for as long as Davis acquiesced to the racist status quo.

Expelled but Undeterred

In 1963, at the very same time as the sit-ins were occurring, the legislature was in session in Little Rock, passing the budget that would fund AM&N — or defund it. If Davis did not toe the racist line, the white legislature was likely to eliminate the college's funding. The college would disappear; the students in his charge would lose their chance at a higher education; the pillar of his educated, affluent, large, and vigorous community would disintegrate. As Davis knew, and as the legislature had reminded him, the African American community in Pine Bluff was self-sufficient only for as long as the whites in power allowed it to be so.

The expelled students were undeterred. On February 28, when the protestors showed up for the 28th consecutive sit-in, they discovered that store management had removed the stools and completely covered the lunch counter, rendering it unusable for a sit-in, but also for serving lunch. They'd shut down the business. It was not a victory for the students (nor for Woolworth's), but neither was it a defeat. The protestors shifted their attention to other local businesses, with similarly mixed results. The police eventually got involved, arresting peaceful protestors for imaginary infractions and denying them food in jail.

And yet, over time, the protestors in Pine Bluff met with success, integrating public pools, registering voters, implementing after-school programs for schoolchildren, seeing that more people of color were hired by local businesses. They integrated restaurants. They carried out costly boycotts. They attended services at white churches. Though sometimes at great cost, the cause they were part of was succeeding.

Related

Watch an Oral History Interview with Pine Bluff Sit-in Participant James Oscar Jones, 2011

In this May 2011 interview conducted for the Library of Congress Civil Rights History Project, James Oscar Jones remembers growing up on a farm in Arkansas, the integration of Central High School in Little Rock in 1957, and attending the AM&N College in Pine Bluff. Jones discusses his involvement in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), meeting activists Bill Hansen and Ben Grinage, participating in sit-ins at Woolworth's in Pine Bluff, and helping African Americans in rural areas become political candidates.Woolworth Anti-Integration Archive, ca. 1963

See the full appraisal page for this segment in our Archive

Ken Gloss estimated the retail value of these documents at $2,000 to $3,000.