The Purloined Portrait: Tracing Poe's Disappearing Daguerreotype

Follow the circuitous story of a rare Edgar Allan Poe daguerreotype that disappeared, but was ultimately found

Mar 27, 2006

Originally published on: Sep 2, 2005

BY Luke Crafton

Sally Guest is an experienced researcher of daguerreotypes with a personal collection she says numbers some 448 pictures — most in little wooden boxes or leather cases — charming, sometimes haunting glimpses into the 19th century.

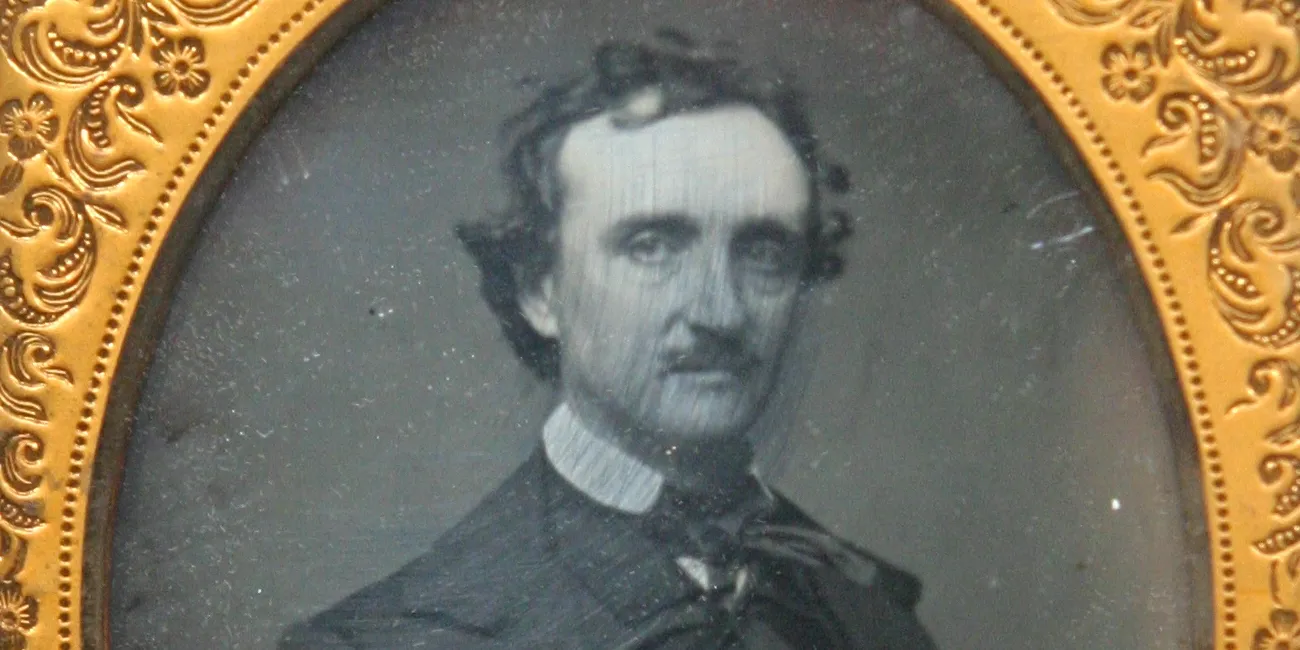

So Guest already knew she might have something valuable when she came to Omaha, Nebraska, in July 2004, with one of her latest acquisitions. From within a small decorative case the image of a man looks out, its metallic surface marred noticeably by a diagonal smudge. But a second look reveals something else, someone familiar: the gloomy stare, rumpled suit and disheveled hair of a macabre literary legend. Edgar Allan Poe.

Early Photography

Daguerreotypy was a landmark achievement of its day. Developed in 1839 by the French chemist Louis Daguerre, it was introduced in the United States soon after. The intricate process involved chemically preparing a polished silver plate to create a photosensitive surface, exposing it to light, then developing the image with mercury vapor and fixing it with a solution of hyposulphite of soda. Though the resulting photographs, often protected within velvet-lined cases, were exceedingly delicate, the images they fixed were much more permanent than those of earlier processes.

But the method was short-lived. Scarcely 10 years old, the Daguerreian era of photography was already near its end in 1849, the year that Poe died mysteriously at the age of 40. Cheaper, less complicated photographic processes quickly supplanted the daguerreotype by the early 1850s.

ROADSHOW Surprise

In her interview with appraiser Wes Cowan, which first aired on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in February, Guest said she was browsing a little "antique/junk shop" in Walnut, Iowa, when a daguerreotype caught her eye amid a jumble of other bits and pieces. As an aficionado of the form — and suspecting the man it depicted might be Poe — Guest says she eagerly paid $96 for the photograph and took it home. She became very fond of the picture, and over the next year, Guest displayed it proudly on her mantel — even though, she says, Poe "is not the best-looking man."

Cowan confirmed on-air that Guest's picture was indeed a daguerreotype of Poe — an amazing fact, given that only six such photographs of the poet were known to exist, he said. Despite the superficial damage to the image (apparently caused by someone having wiped it with his finger) Cowan estimated its value at between $30,000 and $50,000, conservatively, calling it "an incredibly rare portrait." Guest was overjoyed. "I'm thrilled," she said. "I liked the picture anyway, but now I really like it." Cowan said there was no question that a great many people would be willing to compete for the photograph at auction.

Perhaps befitting a story that involves Edgar Allan Poe, from here matters become more intriguing.

The Genuine Article

Guest says that after owning the daguerreotype for about 16 months, she decided she'd like to sell it. To do that, she first needed the picture to be authenticated as a genuine Poe portrait. So she got in touch with the Edgar Allan Poe Society in Baltimore and supplied them with a copy of her daguerreotype; they in turn consulted with artist and historian Michael J. Deas, author of The Portraits and Daguerreotypes of Edgar Allan Poe. Soon thereafter, Guest says, the Poe Society informed her that they believed her daguerreotype was real.

Deas says he recognized the daguerreotype in Sally Guest's possession more or less immediately; the distinctive scratch across Poe's face was the tell-tale sign. Of the small number of Poe portraits that exist, only two bear such blemishes, according to him. Thus Deas believed that quite probably, Guest's daguerreotype was one that he had himself examined up close in 1981, while researching his book at the Hampden-Booth Theatre Library, a private collection located in The Players theatrical club in New York City. Deas called the library; their portrait of Poe was missing.

Enter the FBI

A few months after ROADSHOW's 2004 Omaha taping, and following her contact with the Poe Society in Baltimore, Guest sent her daguerreotype to Cowan, who had agreed to help her sell it. In March of this year, following the Omaha Hour 3 broadcast, Cowan received a call from Special Agent Johanna Loonie with the FBI in Manhattan. The daguerreotype that Guest bought — and believed she owned — was under investigation as a stolen work of art, one that by then had crossed several state borders. Cowan called Guest to let her know that she would be hearing from the bureau.

Then, Cowan says, on April 20 Special Agent David Bass of the FBI's Midwest art crime team arrived at the Cincinnati offices of Cowan's Auctions to take possession of Guest's daguerreotype. According to Jim Margolin, a spokesman for the FBI's Manhattan office, the Poe daguerreotype became an FBI matter soon after the airing of the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW Omaha episode in February 2005. He said the bureau's current assumption is that Guest's daguerreotype is the one reported missing by the Hampden-Booth library, but pending final, official authentication by an expert, the picture remains in FBI custody.

Slow Recovery

As Michael Deas cautioned in a March 17, 2004, Times-Picayune op-ed, "the repatriation of stolen artwork is a difficult and sometimes sensitive procedure." But how long had this Poe portrait even been on the loose?

It's not clear just how recently the Hampden-Booth library may have confirmed that the Poe daguerreotype, which was not on public display, was still in its archives. Ironically, Deas's 1981 research is the last documented viewing of the picture on the library's premises. The library itself has been somewhat reticent. Raymond Wemmlinger, Hampden-Booth's curator and librarian, declined to comment on the situation at present, though he added that the library may be prepared to talk more about it this fall.

According to Margolin, the FBI has not reached the point of pursuing a prosecution in the case, primarily because of the ambiguity surrounding when the picture first disappeared. How it ended up in a little shop in Iowa, whose owners evidently had no idea of its significance or value, only compounds the mystery.

Nonetheless, with advice from her lawyer and Cowan, and in the face of an increasingly ominous investigation, Guest says she quickly realized she would have no choice but to relinquish her innocently purchased portrait. She did just that during a conference call this spring with Special Agent Loonie — although Guest says she still considers it "a donation."

Surprisingly, despite the considerable ordeal and expense of it all (she's not even entitled to her $96), Guest says she feels only mildly bitter about the experience. And though she certainly didn't know it when she bought it, she says she does believe in her heart that the daguerreotype belongs to the Hampden-Booth Theatre Library. Referring to the picture's likely return there, she says, "I'm glad the piece is hopefully where it belongs, that they will take care of it, and that people will eventually get to see it."

Update March 27, 2006:

Since this story first ran in September 2005, the peculiar meanderings of this Edgar Allan Poe daguerreotype, and the dispute surrounding it, seem to have reached an end. According to FBI spokesman Jim Margolin, the portrait's authenticity was finally verified — after delays owing to Hurricane Katrina, which damaged the home of the New Orleans-based authenticator — and the FBI returned the daguerreotype to the Hampden-Booth Library in New York City on November 8, 2005. Raymond Wemmlinger, the library's curator, confirmed that the Poe picture is once again back in the library's possession and, after an absence of many years, available for viewing by qualified researchers.

Update July 23, 2018:

Sold! ... Only a few months after the Poe daguerreotype was finally authenticated and returned to the Hampden-Booth library, it was put up for auction at Sotheby's in October 2006 and sold for the final hammer price of $150,000. The proceeds of the sale went to benefit the Hampden-Booth.

Related

Watch the original full appraisal of the daguerreotype in our Archive