The Washington-Custis Connection

More on Martha Custis Washington, America's first First Lady.

Mar 26, 2007

BY Ben Phelan

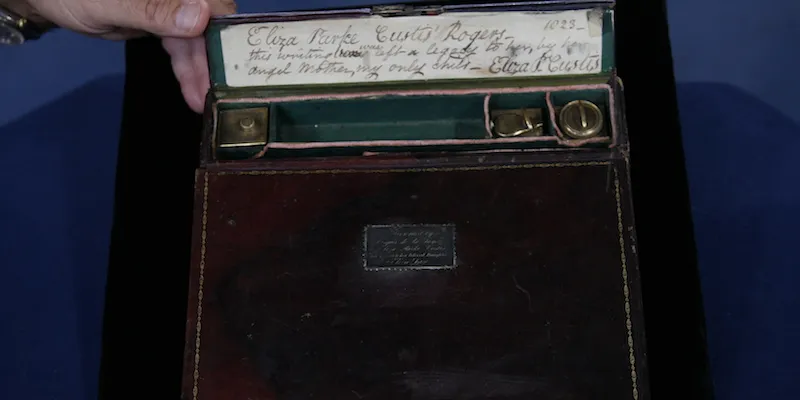

The lap desk that Mike, from Birmingham, Alabama, brought to the ROADSHOW in Mobile in the summer of 2006 is a fantastic illustration of how the value of an elegant, if unremarkable, antique can balloon because of its intersection with historical figures. The Custis family's history, and how it joins up with the history of the Washington family, is a little intricate; but it shades into the history of the republic as a whole, implicating not only our first President, but the first First Lady and the Marquis de Lafayette. A quick biographical sketch should clarify how a common ladies' writing desk could now be valued at between $30,000 and $50,000.

Martha Dandridge was born in 1731 into a gentrified family of considerable, though not extravagant, wealth, in New Kent County, Virginia. Throughout her girlhood, and until she married George Washington, she went by Patsy. But before becoming Martha Washington, Patsy was married to Daniel Parke Custis, a gentleman farmer and heir who was two decades her senior and a couple of rungs above the Dandridges on the social ladder.

By all accounts, Daniel's father had been something of a tyrant, and was probably the reason Daniel remained a bachelor till the age of 37. He had prevented Daniel's sister from marrying by refusing to hand over the dowry, and rejected Daniel's own romantic interests for financial reasons—or so he said, though the claim is hard to credit: one of Daniel's sweethearts was an heiress herself. In all events, he kept Daniel on a short leash, and forbade him from marrying a Dandridge. But Daniel defied him, and he and Patsy married in 1750 when she was 18. They moved into a two-story dwelling called, ironically, White House, and had a happy life together, albeit a short one.

Their first two children, Daniel Jr. and Frances, did not survive childhood. And only three months after Frances' death, Daniel Sr. and 2-year-old Jack both contracted a serious illness, possibly scarlet fever, which Jack barely survived. Daniel did not; he died in 1757, leaving Patsy a 26-year-old widow and mother of two — Jack and Patsy, their youngest. But to her good fortune, Patsy, who would go by Martha after the birth of little Patsy, was a widow of means, and had her pick of suitors. One of them, we now well know, was George Washington.

George and Martha did not have any children together. Nevertheless, George was a devoted father to Jack and Patsy from the time of his marriage to Martha in 1759. In 1776, just a month after the Colonies declared their independence from Great Britain, Jack's wife, Eleanor, gave birth to George and Martha's first grandchild, Eliza Parke Custis, the eventual recipient of the lap desk. A year later, the Marquis de Lafayette sailed from France to meet the world-famous General Washington, commander-in-chief of the Continental army, and aid him in Americas' revolutionary cause. Ultimately, Lafayette was to prove instrumental in the Colonies' victory over the British. He formed a close friendship with Washington, and it was the Marquis who would eventually make a gift of the lap desk to Eliza, who in turn gave it to her own daughter (also named Eliza) when she was only a year old.

Today, for obvious reasons, lap desks are not as common as they once were; and as lovely a piece as the Custis lap desk is, it seems unlikely that either Eliza or the Marquis could have imagined it would appreciate to its current value, which appraiser Wes Cowan estimated at about $40,000. From Mike's stunned silence when he was told of the possible value of a piece he picked up, almost by chance, at an estate liquidation, we can imagine it was a shock to him, too. I wonder if my iBook will ever be worth $40,000? Probably not, but I think I'll hold onto it anyway, far into its obsolescence.