Translation, Please...

Ever since she was a girl, the owner of a highly embellished 18th-century pistol wondered what the Arabic engraving on it means.

Jan 23, 2006

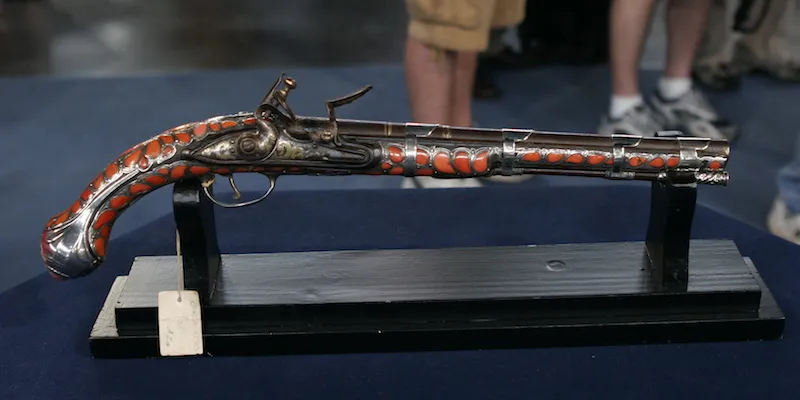

When Anne, a visitor to the Tampa ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, was just 10 years old, her father, a gun collector, came home with an 18th-century flintlock pistol decorated with red coral, gold and silver. It was love at first sight.

"It's pure romance to me," Anne said when she described the pistol on-air at the Tampa ANTIQUES ROADSHOW. "It's pirates, Barbary Coast, Lawrence of Arabia."

She inherited the gun from her father, and has always wondered what the Arabic-looking inscription on the side of the pistol meant. Paul Carella, the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraiser who assessed the flintlock pistol on-air, said that it might have been owned by pirates, as Anne had dreamed. Paul also wondered about the Arabic inscription engraved in gold.

"I can't read Arabic," he told her, "but I would actually suppose that this is either the maker's name or it's actually a date."

Anne left ANTIQUES ROADSHOW as curious as she ever was, eager to have the mysterious engraving translated. She began her hunt by contacting two local gun dealers, but one was too busy to take a look, and another doubted the gun's authenticity. "I just came back from the ROADSHOW," she told him before moving on. "I assume they know what they're talking about."

Anne says the pistol has always reminded her of "pirates, Barbary Coast, Lawrence of Arabia."

Anne also began an exhaustive search on the Web. "I was online for about a week straight after the show," she says. She searched on phrases such as "18th century flintlocks," "Arab and Turkish weapons from the 18th century," and "Antique European weapons from the 18th century."

Her online search brought her to a European Web site that offered online appraisals of antique guns. Anne sent digital images of the pistol, and for $5 a Belgian expert responded, writing that the Arabic engraving "could be those of the artist who decorated the pistol or even those of an Arabian barrel maker." It was apparent to Anne, though, that the European dealers were going on conjecture: they couldn't read the Arabic either.

The gun is decorated with coral inlay and gold and silver metalwork.

Anne says she learned the most about the pistol in face-to-face meetings with local experts on a single day in September. Anne visited Chuck Love, an expert in 18th-century guns who owned Love's Gun and Pawn Shop in Deland, Florida. He confirmed that the pistol was authentic and said he believed that it wasn't owned by pirates—they used more utilitarian guns—but was owned by a potentate who commissioned the decorated firearm as a status symbol. The only way a pirate would have got hold of such a gun, Love believed, is if he stole it. Love also educated Anne about how flintlocks work, and he wouldn't let her leave his shop without taking a gun case to protect her treasure, which she had been lugging around in a towel.

That same day, Anne visited Yahya Al' Raggad, an Arabic professor at Stetson University in Deland. He was fascinated with the gun, and used a magnifying glass to better examine the gold inlay. The Arabic word baak meant "noble," he told her, which indicated the gun was indeed owned by a nobleman. Underneath it was the word Sulayman a surname, and then saheb which means "owner." So the inscription didn't name the pistol's maker, or the artist who decorated it, or the year it was made. It named the rich nobleman who likely paid to have it made.

Anne's research has erased some of the mystery surrounding her antique firearm—as well as most of its pirate mystique—but what she has discovered has sparked her imagination in a new way. "I'd love to find a picture of a sheik with this gun on his hip," Anne says. "but I know that's a pipe dream."