What Was the Boxer Rebellion?

Learn more about this traumatic upheaval in the history of modern China.

A stunning Chinese bowl, elaborately decorated with cobalt blue in a traditional Tibetan style, featured during ROADSHOW's 2004 visit to Omaha.

Nov 2, 2016

Originally published on: Jan 4, 2005

When the ROADSHOW visited Omaha in summer 2004, a visitor named Julie brought a stunning Chinese bowl, elaborately decorated with cobalt blue in a traditional Tibetan style, which she inherited from her great-grandmother.

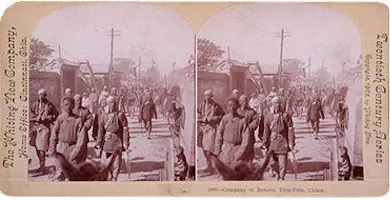

A contingent of Boxers, Tientsin, China, 1901. Very few photographs of Boxer troops have survived.

She explained to appraiser Lark Mason, an expert in Chinese art with igavel.com in New York City, that her ancestor had received the bowl as a gift from some residents of Beijing around 1900 while stationed there with her husband, who was secretary to the American ambassador. Julie told Lark that the gift was in gratitude for the kind treatment the locals had apparently received from the American couple during the violent social upheaval of the Boxer Rebellion. But what exactly was this strangely named event?

The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 was one of the defining moments in the history of Chinese nationalism, and the first major rebellion in that country against imperialist powers, including the English and the Japanese, involving issues of international tension that resonate to the present day.

The bloody peasant revolt was led by members of a group known as the Yi Ho T'uan, or the Righteous and Harmonious Fists, a centuries-old secret society in China whose members practiced a form of shadow boxing that they believed gave them supernatural powers. The Boxers, as they were called in English, had a belief system that drew from Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist strands and also opposed the influences of foreigners. The ranks of the Yi Ho T'uan swelled after flood and drought struck the country in 1898 and 1899, exacerbating the poverty and foreign aggression that already plagued the country. The Boxers were further provoked by Christian missionaries and converts who often disrespected Chinese traditions.

Chinese Christians who were gathered at the Apostolic Mission during the bombardment of Tientsin.

Heading 3

Heading 4

Heading 5

The secret group allied themselves with anti-foreign members of their government and in the summer of 1900, bands of Boxers freely roamed the countryside around Peking looking to destroy all things foreign. They burned houses, missions and schools, and slaughtered hundreds of Chinese Christians, missionaries and practically anyone else that they believed supported foreign ways. The Chinese dowager empress, Tz'u His, supported the rebels and declared war on the foreign powers.

The rebellion only ended after an armed force of 20,000 from eight nations crushed it. The Manchu government signed an agreement with the foreign invaders in which the Chinese agreed to execute some of the leaders of the rebellion, destroy its forts, and pay $330 million in damages and reparations. In large part because of the humiliating conclusion to the rebellion, the Ch'ing dynasty collapsed little more than a decade later, leading to the establishment of China as a republic.

The Chinese Communists, who came into power in 1949 under the revolutionary leadership of Mao Zedong, have stressed the strong nationalist strains that were part of the rebellion. Former Chinese Premier Chou En-lai went so far as to call the Boxer Rebellion "one of the cornerstones of the Chinese Revolution."

Related Content

Fei Ch'i-hao: The Boxer Rebellion, 1900

An overview from the the Modern History SourceBook, a website hosted by Fordham University.