Who Can Authenticate a Warhol?

How can someone tell if the Andy Warhol piece they have in hand is authentic or fake? It's not an academic question: Warhol pieces often sell for tens and even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Dec 19, 2016

Originally published on: Mar 26, 2012

Editor's note 12.19.2016: As of 2012, the Andy Warhol Authentication Board, Inc. has been dissolved.

The 1963 Warhol work "Green Car Crash" sold for nearly $72 million in 2007, placing it in the stratosphere of modern art auction prices.

"He's the most coveted pop artist," says Meredith Hilferty, who heads the Fine Arts department for Rago Arts in Lambertville, New Jersey; Hilferty appraised a Warhol silkscreen that turned up at the El Paso ROADSHOW in June 2011. "Everybody recognizes a Warhol and wants to own one," she told us.

Everybody recognizes a Warhol and wants to own one

For a number of reasons, authenticating a Warhol is often more complicated than authenticating the work of other artists. Warhol was a prolific artist who left behind an immense body of work after his death in 1987. "Other artists have a few hundred paintings, and each one is documented," says Hilferty. Warhol, though, produced many thousands of pieces, many of which were at least partly executed by others working in his studio, known as The Factory. Works are still being added to Warhol's multi-volume catalogue raisonné, which lists each known painting, drawing, or sculpture, what they were made of, where they were exhibited, characteristic features, and provenance. Authentication is also complicated because most of Warhol's pieces aren't images created from scratch. Instead, the pop artist appropriated them―think of Warhol's iconic silkscreens of Marilyn Monroe or Mick Jagger, which he based on existing popular images.

"His pieces evoke a Xeroxed-copy look," Hilferty says. "If someone is in the business of faking things, Warhol is an attractive place to start because most of his imagery is photographic with flat colors." For that reason, and the price they can fetch, there are "many Warhols out there that aren't Warhols," she says. But at the same time, many of these impostors were not created to fool the market, Hilferty says. They were created as reproductions, such as postcards or posters, purchased as such, and then inherited by owners who now want to know if they have value.

The Andy Warhol Authentication Board

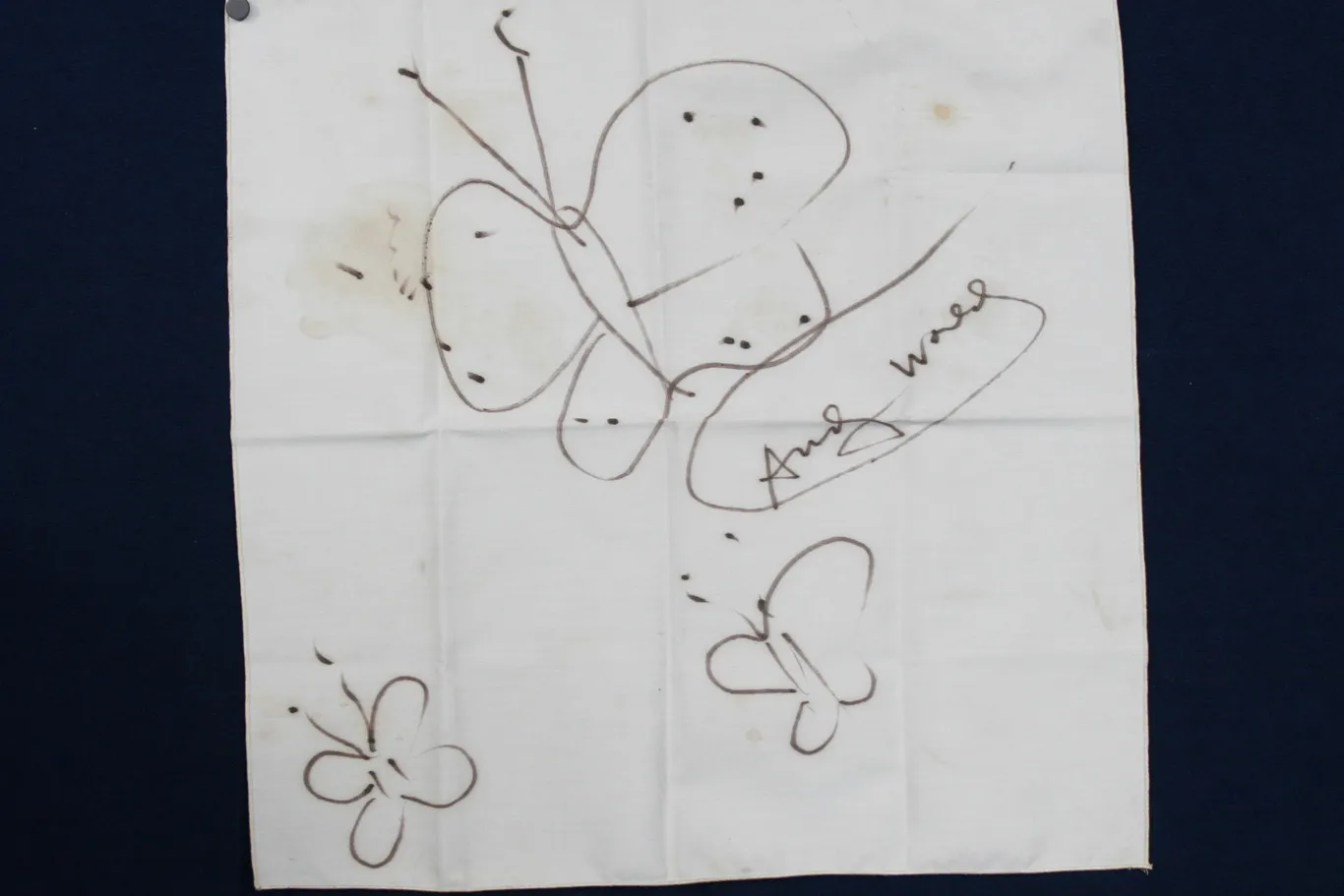

Until recently, the arbiter of questionable Warhols was the Andy Warhol Authentication Board, part of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, based in New York City. In 2006, for example, a guest arrived at the ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in Honolulu with three butterflies doodled onto a linen napkin that he believed Warhol had drawn and signed. ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraiser Kathleen Guzman told the guest that without authentication from the Board such a piece "doesn't exist in the world of Andy Warhol." The guest sent the linen to the Board, and they deemed it a Warhol. Their approval bumped the value of the piece to $30,000.

But in the fall of 2011, after a series of controversial decisions, the Warhol Authentication Board announced it was closing up shop after having evaluated roughly 6,000 pieces over 15 years. In 2011, it was revealed the Board spent $7 million over three years to defend itself from a lawsuit by collector Joe Simon-Whelan, who sued when the Board refused to authenticate a Warhol portrait he owned. The money spent running the Board — about $500,000 a year — will be re-allocated to the Foundation's arts grants.

"We'd rather our money go to artists, not lawyers," Michael Strauss, chairman of the Foundation's board, told the Wall Street Journal in October 2011.

Now, the best way to get an uncertain Warhol appraised is to submit it to the Foundation, which is still in the process of listing Warhol pieces for future volumes of Warhol's catalogue raisonné. If a piece is included in the raisonné, it's assumed to be a Warhol. "You're going to walk away with the same answer," Hilferty says, "but it won't be quite as cut and dried." If it isn't included in the Warhol catalogue, "there's not much you can do in terms of selling the piece as a Warhol," Hilferty says.

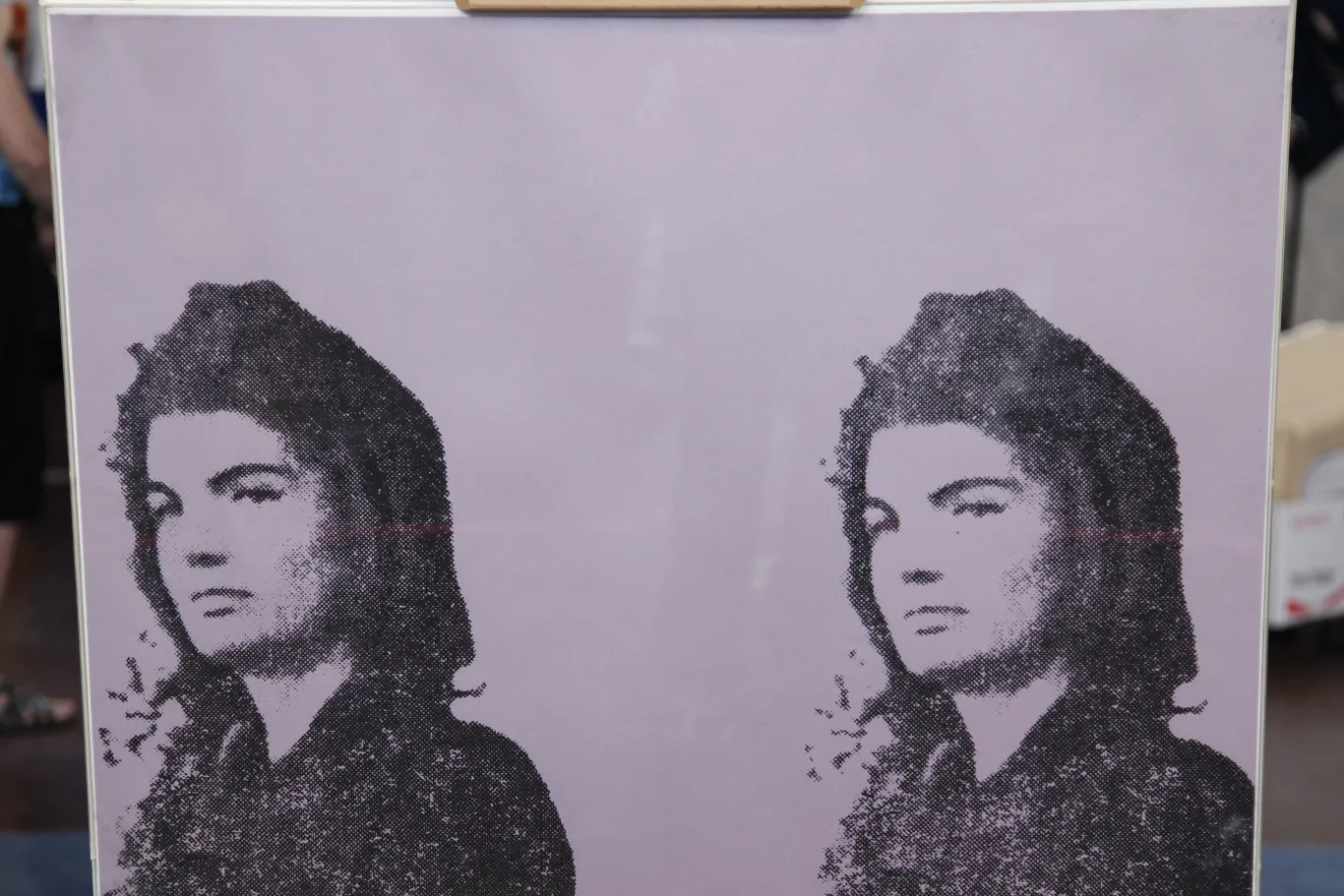

In the meantime, Warhols will be assessed like the art of any other artist — by experts familiar with their work. Hilferty confirmed the authenticity of the "Jackie II" silkscreen that came to El Paso in the summer of 2011 based on others she'd seen in the "Jackie" series, evaluating the paper, its size, the ink, the stamp, signature, the print number, and the location of the markings. "There are features that are specific to Warhol," says Hilferty, who valued the piece at about $20,000. In "Jackie II," for example, Warhol used a pearly lavender ink "you can't reproduce on an inkjet printer," she says.

In El Paso, a guest brought in another Warhol silkscreen that ANTIQUES ROADSHOW appraiser Simeon Lipman also valued at roughly $20,000. He confirmed the authenticity of the Campbell's soup can silkscreen partly on the piece's signature, which was consistent with other Warhol signatures from the early 1980s. Its authenticity was cemented by the documented friendship between the owner and Warhol. "He got the piece from Warhol himself," Lipman said, noting Warhol's dedication to the guest written on the back of the print, "which is the best provenance you can get."

Related

1966 Andy Warhol "Jackie II" Artist's Proof -- One of the most widely recognized images of Jacqueline Kennedy, an Andy Warhol print titled "Jackie II," produced in 1966, showed up in El Paso during ROADSHOW's 2011 visit. Appraiser Meredith Hilferty evaluated the print, pointing out that it was an artist’s proof and came from a portfolio called "11 Pop Artists.' According to Hilferty, "Warhol prints are highly desirable. Jackie particularly is one of the images that people like. The replacement value on this print we would expect to be around $20,000."