Who Faked the Texas Independence Documents?

Time and again on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, we hear that valuable items can inspire forgeries, and the highly desirable imprints of the 1836 Texas Declaration of Independence did, in fact, spawn some very convincing fakes.

Feb 2, 2015

“We, therefore, the delegates with plenary powers of the people of Texas, in solemn convention assembled, appealing to a candid world for the necessities of our condition, do hereby resolve and declare, that our political connection with the Mexican nation has forever ended, and that the people of Texas do now constitute a free, Sovereign, and independent republic...”

— From the Declaration of Independence of Texas, March 2, 1836

Baker and Borden of San Felipe are thought to have printed 1,000 copies of "The Unanimous Declaration of Independence made by the Delegates of the People of Texas in General Convention at the Town of Washington on the 2nd day of March 1836." In the 1960s, over a century later, Texans who had profited in large part from the success of the oil industry began searching for and collecting rare Texana (items with historical and/or cultural significance to Texas). The Declaration broadside was a must-have document to several serious collectors, and copies were being sold for $20,000 or more by the early 1980s. As we've heard time and again on ANTIQUES ROADSHOW, valuable items can inspire forgeries, and the highly desirable imprints of the Declaration did, in fact, spawn some very convincing fakes.

Host Mark L. Walberg and expert Wes Cowan discuss faked Texas Declaration of Independence documents in Austin, Texas.

During our visit to Austin in June of 2014, ROADSHOW host Mark L. Walberg and appraiser C. Wesley Cowan compared an original broadside printing of the Declaration with one of these very good counterfeits at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission (the counterfeit was on loan from the Briscoe Center at the University of Texas at Austin). Cowan discussed how the fraudulent copies were discovered when printer and book dealer, W. Thomas Taylor, became suspicious of the growing number of Declarations on the market. With the help of other experts, Taylor, who had sold three copies of the Declaration himself, was dismayed to discover that a number of copies were forgeries.

As he outlined in his book, Texfake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents, Taylor documented that there were only a handful of known copies of the Declaration in 1970, but by the late-1980s Taylor could find almost 20. This bothered him. After extensive research looking at every copy he could, Taylor determined there were 10 authentic, original broadsides with a legitimate provenance. The rest, he concluded, with their fuzzier type and narrower columns, were forgeries. Tom Taylor followed the ownership trail of the known fakes and discovered that every forgery had been sold by one of three Texas dealers: John Jenkins, William Simpson, or Dorman David.

“These fakes fooled a lot of people for a long time,” said Cowan.

"These fakes fooled a lot of people for a long time," said Cowan. "The one person who finally admitted to faking the documents, long after the fact, was Dorman David." Jenkins and Simpson always maintained that they had no knowledge that anything they sold was a forgery. Cowan added, "Jenkins and Simpson always professed innocence."

David admitted to Taylor and at least two journalists that he had reproduced the Declaration, although he said it was his intention to one day sell them as facsimiles. In a December 1989 New York Times Magazine article, "Lone Star Fakes," reporter Lisa Belkin described what happened:

Over a recent lunch with this reporter, David cheerfully admitted that he had reproduced copies of the Declaration. She continued, David explained that, as Tom Taylor had suspected, he photographed the one genuine copy he owned and made a negative that was much larger than the original. He repaired any damage visible on the magnified copy, then created a zinc plate from the negative and printed his fakes. His ink was a home brew, made by lighting a candle, collecting its smoke in a paper bag, and mixing the carbon that attached to the bag with various oils. His paper came from blank end pages in old books. But why did David make the forgeries? "There's speculation," Cowan explained, "that besides money, of course, there was also, perhaps, ego involved. The faker [David] was a flamboyant dealer who spent huge sums of money to buy rare Texas documents and sell them. He invariably got into trouble though with buying too high [and] that forced him then to sell low. And the same dealers were taking advantage of him, over and over again, and there's some speculation that he did this to get one over on those guys — to knock that chip off their shoulders."

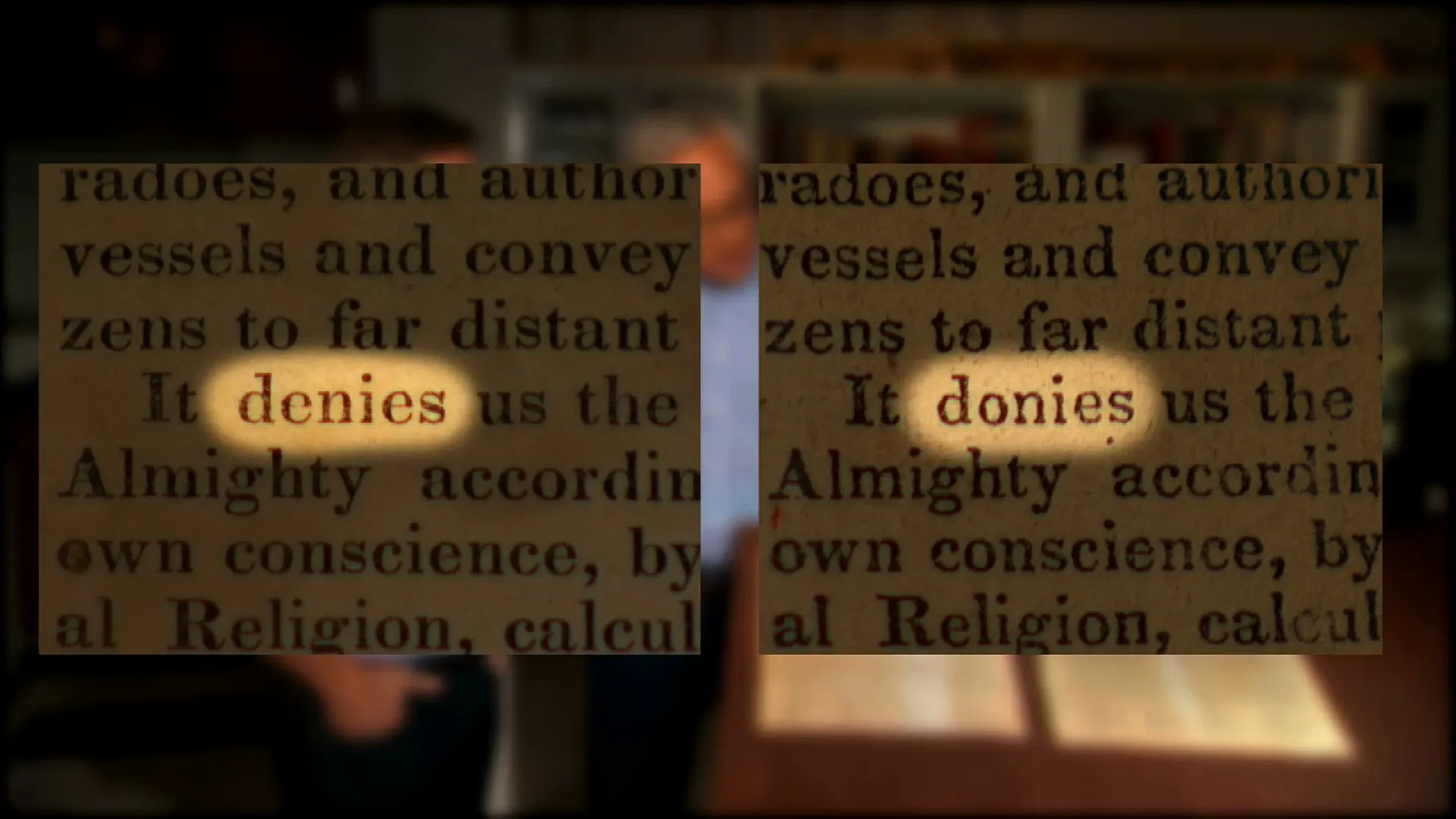

As expert Wes Cowan pointed out in the segment, despite bearing tell-tale signs of forgery, including typographical errors like the one pictured here, fake Texas documents have fooled many people over the years.

Adding up David's complicated history of bad business dealings, alleged participation in a criminal ring that stole countless historic documents from public institutions (some purported to have been sold at his auctions), and several years of drug abuse and running from the law, Taylor pointedly directs his readers in Texfake how to draw their own conclusions about David's intentions with the Declaration copies.

Once he uncovered the truth, Taylor knew that two of the three Declarations he had sold were counterfeit. He reimbursed those clients.

No one was ever prosecuted for creating or selling the forgeries. John Jenkins died in 1989 under mysterious circumstances, his body found near Bastrop, Texas, with a bullet in the back of his head (the local sheriff declared it a suicide). William Simpson died in 2001. Dorman David died in 2013.

The price for an authentic Declaration of Independence of Texas today could fetch up to $1 million, according to Cowan. But do the fakes have value? "If you own the original, you gotta have a fake, right? I mean it's a big story and it's part of the whole history of the document. … What would a collector who owned the original pay for a fake? A thousand dollars maybe? Maybe."

Related Resources

Texfake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents, by W. Thomas Taylor, 1991

Unanimous Declaration of Independence by the Delegates of the People of Texas, at the State Library and Archives Commission