Who Was "Horny"? Henry Hornbostel, That's Who

George Sotter's unusual dedication was far more respectable than it sounds!

Dec 10, 2010

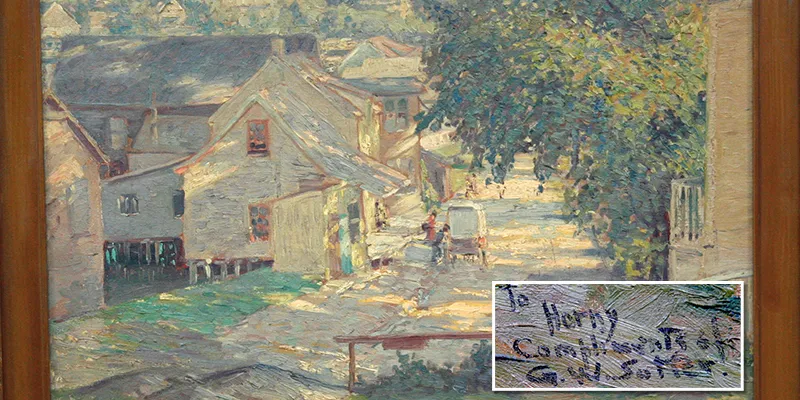

At the Philadelphia ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in August 2006, a painting by American artist George W. Sotter arrived with a mysterious dedication written in the corner that read

To Horny Compliments of G.W. Sotter.

ANTIQUES ROADSHOW paintings appraiser Nan Chisholm, of New York, knew the signature was that of George W. Sotter, the Pittsburgh landscape painter from the early 20th century, but confessed she didn't know who "Horny" was. The owner wondered on-air if it might refer to his mother, who wanted to be an artist and a racecar driver. "She was a very adventurous woman," the man said. "And I can't say for certain whether or not that was her nickname or not."

After the episode aired, ANTIQUES ROADSHOW received an email from Patricia Lowry, the architecture critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, who believed that the reference to "Horny" was probably far more respectable than its owner suspected. She wrote, "The inscription 'To Horny' would have been to Henry Hornbostel, architect and head of Carnegie Tech [College of Fine Arts] where Mr. Sotter taught. 'Horny' was his nickname."

Was Lowry's interpretation right?

Henry "Horny" Hornbostel

To find out, we contacted Charles Rosenblum, an assistant professor at Carnegie Mellon's School of Architecture, who is writing a book on Hornbostel. Rosenblum confirmed that Hornbostel was an architect from the early 20th century informally called "Horny," an abbreviation of his name. "He won more design competitions than any other architect of his time," Rosenblum says. "He was all over the architecture magazines, just short of a household name." In all, Hornbostel designed 228 buildings, bridges, and monuments in the United States. Rosenblum describes the architect as "charismatic and popular," known for red silk ties, costume parties, quick humor, and dynamic teaching.

Hornbostel spent his career improvising with the Beaux Arts style, a neoclassical architectural discipline taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where Hornbostel studied. Hornbostel used the style as his vocabulary for a wide range of buildings, including Oakland City Hall, which turned "a city hall into a skyscraper, for the first time in American history," Rosenblum notes, a style mimicked in city halls across the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. Hornbostel also collaborated with engineer Gustav Lindenthal on the Queensborough, Williamsburg, and Manhattan bridges in New York City.

More than once, Hornbostel designed college campuses, including Northwestern and Emory Universities. In the book, Invisible Giants — Fifty Americans Who Shaped the Nation But Missed the History Books, Michael Graves, the architect and designer, said that the Emory campus "approaches in quality Thomas Jefferson's much lauded and appreciated designs for the University of Virginia in Charlottesville" — quite some praise.

Colleague of George Sotter

Rosenblum also confirmed that Sotter and Hornbostel crossed paths at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, the forerunner of what is today Carnegie Mellon University. In 1904, Hornbostel won Andrew Carnegie's competition to design the buildings and campus for that institute and became the first director of the school of architecture and then the dean of fine arts. Sotter came on as a painting teacher, and Hornbostel commissioned him to paint six murals depicting Pittsburgh for his fine arts building.

"I would say with 99 percent certainty that the reference was to Hornbostel given they worked both in and on the same building and that 'Horny' was his nickname," Rosenblum says.

Hornbostel's buildings on campus and off — 110 in all — became Pittsburgh landmarks, including the Rodef Shalom synagogue, the Schenley Hotel, the University Club, and the upper campus of the University of Pittsburgh, as well as the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial. They added a refined presence to what had been a grim industrial city.

But Hornbostel's career was ended by a dearth of commissions during the Great Depression, a career that landed in declining Pittsburgh rather than architectural meccas such as New York and Chicago, and the ascent of modern architecture. He retired from architecture in 1939.

"He definitely was not a revolutionary," Rosenblum says, "And when the revolutionaries come, they don't appreciate their forbearers." Yet Hornbostel hasn't been completely forgotten — 22 of his creations have been placed on the National Register of Historic Places.