Who Was the Real Person Behind Fielding's "Female Husband"?

Fictionalized by novelist Henry Fielding in 1746, Charles Hamilton’s story became the first widely distributed account of a “female husband.” Hamilton was someone whose gender non-conformity in the 18th century is now being further explored and contextualized.

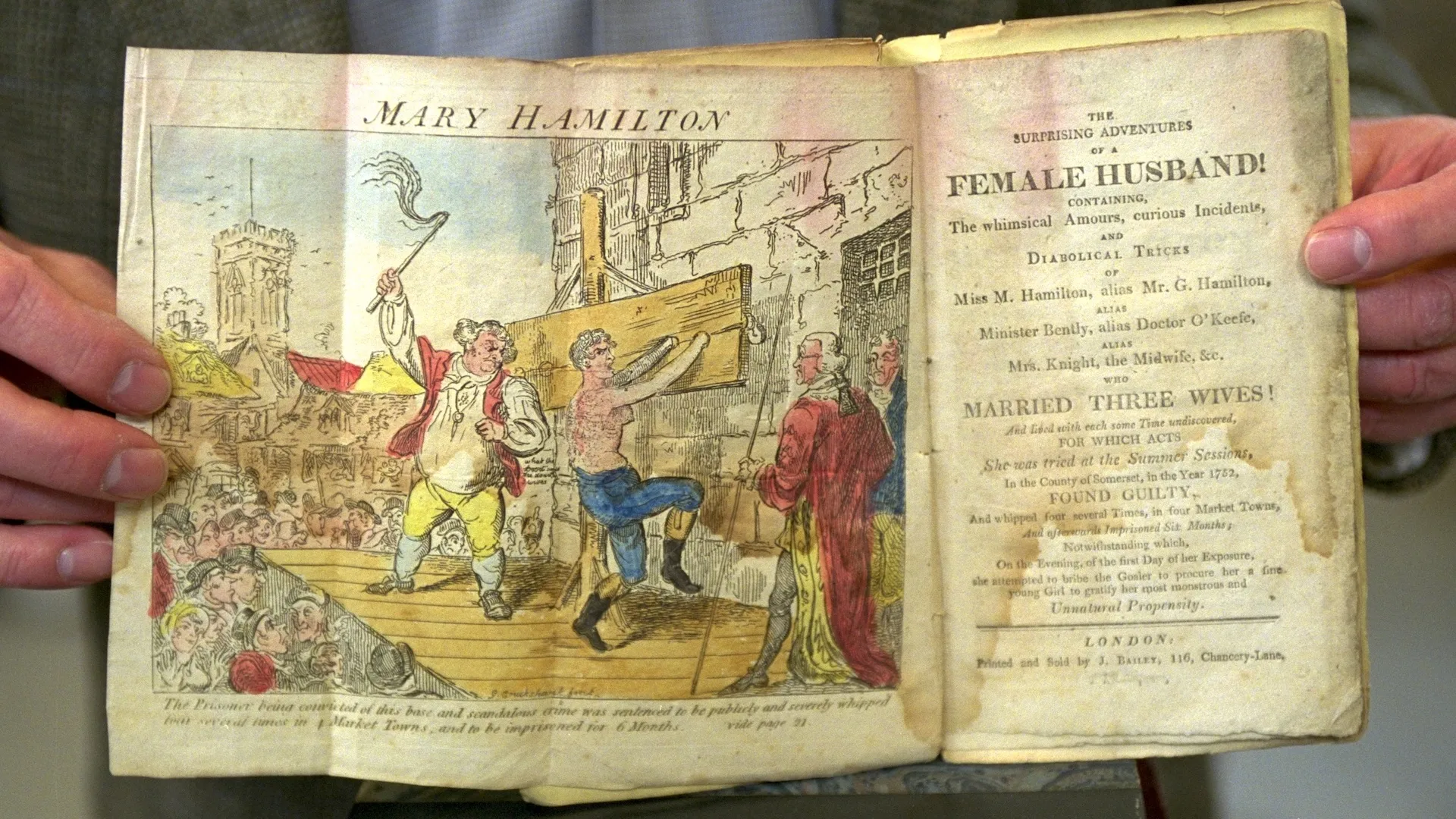

The frontispiece illustration and title page of an 1813 edition of Henry Fielding's publication "The Female Husband."

Dec 20, 2021

Editor’s Note: Although Charles Hamilton was referred to as “she/her,” ”he/him,” and sometimes both sets of pronouns, in court and in print, during their lifetime, it’s impossible to know how Hamilton perceived either their gender or sexual identity. This article will use the pronouns “they/them/their” to refer to Hamilton.

FIRST FEATURED in an ANTIQUES ROADSHOW episode from Seattle in 2003, the appraisal of an 1813 volume of The Female Husband, a short, sensational pamphlet or novella, by the English novelist Henry Fielding, is memorable for more than one reason.

To begin with, it’s not often that a guest comes to ROADSHOW claiming to have inherited his mother’s “pornography collection” — as this guest named Vincent did, to appraiser Selby Kiffer’s surprise. And second, the subject matter of the book, having been based on a real person, was the 18th-century equivalent of one of today’s ripped-from-the headlines page-turners.

In Fielding’s story, a woman dons men’s clothes to trick several unsuspecting women into marriage for personal and financial gain, as well as to satisfy their “most monstrous and unnatural desires.” She is ultimately caught, tried and publicly whipped.

Reading from the book’s frontispiece, appraiser Selby Kiffer, Fielding’s tale recounts

The surprising adventures of a female husband! Containing the whimsical amours, curious incidents, and diabolical tricks of Miss M. Hamilton, alias Mr. G. Hamilton, alias Minister Bentley, alias Dr. O'Keefe, alias Mrs. Knight, the Midwife, et cetera. Who married three wives and lived with each some time undiscovered for which act she was tried in the summer session in the county of Somerset in the year 1752, found guilty and whipped several times.

First published in London in November 1746, Fielding’s The Female Husband was revised and reprinted many times over several decades, sometimes as excerpts in magazines, and even made its way into publications across the Atlantic. It’s the type of fiction that would arguably still catch readers’ attention, having dramatic elements of polygamy, courtroom spectacle, and of course the main hook: the revelation that one particular central character is more complex than meets the eye.

Yet Fielding’s “female husband,” a.k.a. George Hamilton, was based on a real-life individual: one Charles Hamilton. In Female Husbands, A Trans History, author Jen Manion says that female husbands like Hamilton “exposed what was to remain hidden and revealed the incoherence of something that was supposed to be clear. For this they were deemed social outliers and marginalized historic subjects.”

Like many marginalized identity groups, LGBTQ figures in history have often been difficult to research, their queerness being disputed by historians, evidence of their relationships being hidden for years, or even erased from historical accounts.

It’s important to keep in mind that in the 18th century, English and Colonial American societies were rigidly structured around heteronormative and gender-binary social norms, predating any now-familiar modern concepts of transgender, lesbian, gay, bisexual and queer identities. (For example, the earliest-known recorded use of the now outdated word “homosexual” is from 1868, and “transgender” was coined only in 1971 — both well past the life span of Charles Hamilton.)

Charles Hamilton was born in Scotland, assigned female at birth and called Mary Hamilton as a child. Hamilton left home at the age of 14 wearing the clothes of their brother, and then, living as a man, began a career posing as a doctor, traveling from town to town. Hamilton met Mary Price, the niece of their landlady, and the two married in a legal ceremony in July of 1746 in Wells, England.

Manion argues that Hamilton’s decision to take on a male identity was not merely a costume of convenience in order to escape the restrictive and limited role of a woman in that society at that time:

In the case of female husbands in particular, it is impossible to isolate economic and social power from gender and sexual freedom. Sexual freedom — including freedom to have sex with women, to not have sex with women, to not have sex with men, or to not have sex at all — was at the heart of the vast range of social powers that accompanied manhood. And tragically, it was a key practice for which female husbands were punished.

Two months after they were wed, Mary Price reported Hamilton to authorities in Glastonbury, claiming she’d been duped, that her husband was a woman, and she wanted her marriage voided.

The case was unprecedented. At the time, there was nothing specific in British law that made it illegal to be a person who was assigned female at birth, but live as a man married to a woman. And Price testified that she and Hamilton had had a sexual relationship. Therefore Hamilton was not only upending gender norms living and working as a man, but also engaging in a sexually active, legal marriage. So how would the law proceed in this unusual case?

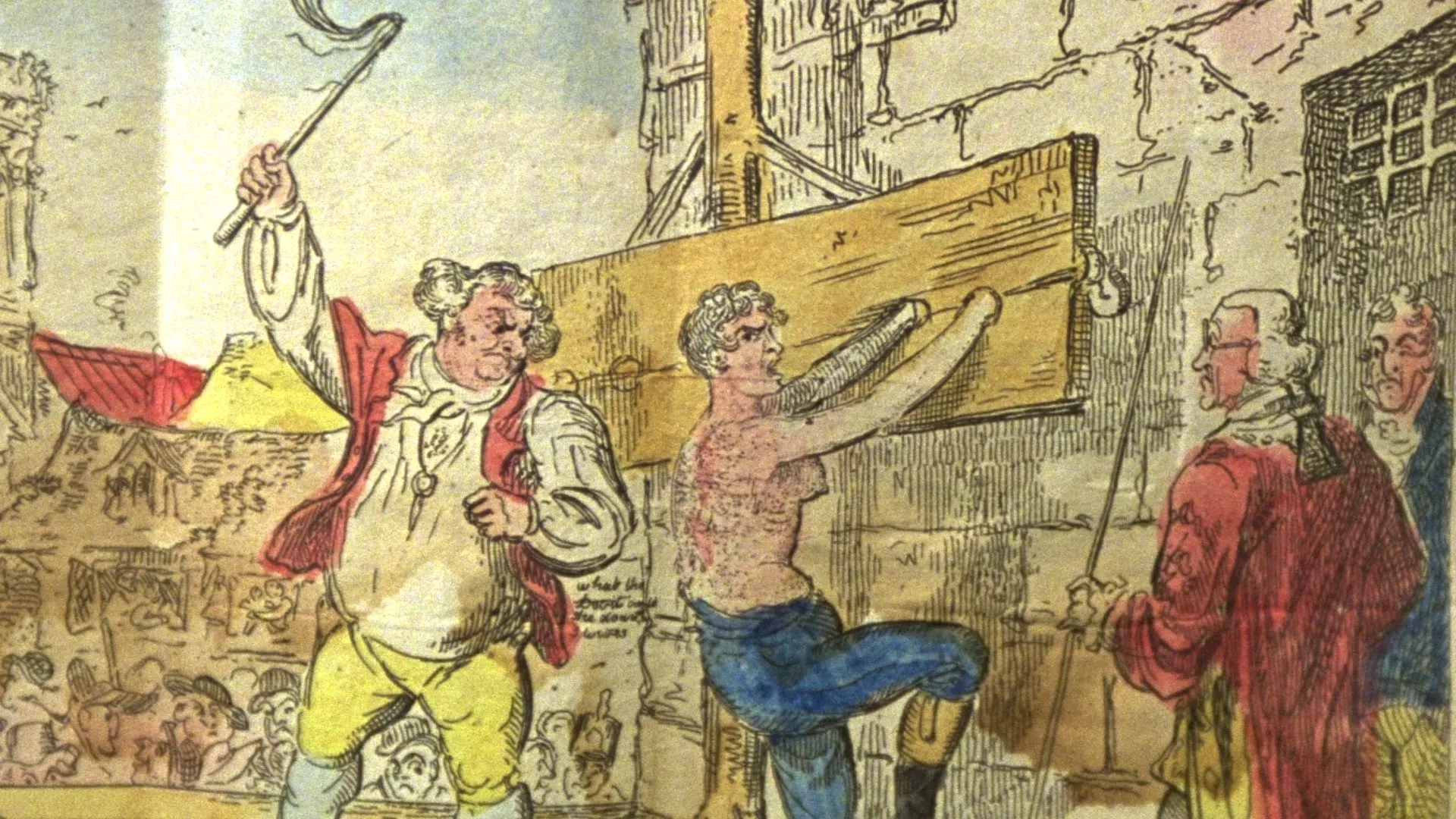

Detail of the frontispiece illustration from an 1813 edition of Henry Fielding's pamphlet "The Female Husband," depicting Mary Hamilton being publicly whipped.

Hamilton ended up being accused of violating vagrancy laws. The Vagrancy Act of 1744 primarily focused on deceitful ways of making money and was used to charge people for a variety of transgressions (to name just a few: fortune tellers, unlicensed peddlers and men who abandoned their wives and children).

Hamilton’s punishment was six months of hard labor, as well as a public whipping in each of the four towns within the county that they had visited professionally as a quack doctor. Manion asserts that for the community of Glastonbury, “Hamilton was a grave threat — and their ability to engage in sex with a woman as a man was at the heart of this threat. By their very existence, they exposed the instability of sexual difference and the imitability of heterosexual sex.”

Assuming Price was truly unaware of Hamilton’s secret, in addition to Hamilton’s deceit, Manion argues that the court was also demanding Hamilton be publicly humiliated for subverting the societal standard of a gender-binary, heteronormative relationship. An example had to be made, and Fielding’s Female Husband, with its exaggerated details and color illustration of Mary Hamilton, a.k.a. George, being whipped in public, conveyed a clear warning far beyond the county limits not to transgress societal norms.

What happened to Hamilton after they served their sentence? Manion’s research indicates they appear to have emigrated to the British North American Colonies, continuing to live as a man and work as a quack doctor. Additionally, unlike Fielding’s George Hamilton character, who married multiple women, there is no historical evidence of Charles Hamilton ever having married anyone other than Mary Price.

Reports of other gender non-conforming people marrying women would continue to surface after Hamilton’s story became known. But as Manion states,

Charles Hamilton was the original female husband. While not the first person assigned female to live as a man and marry a woman, Hamilton was the first person to do so who was characterized as a “female husband.” This designation took on a life of its own in the ensuing decades, creating a catchy, memorable, and succinct way to describe transing gender and same-sex love all at once.

Eighteenth-century English society was concerned with punishing Charles Hamilton’s gender non-conformity, but three centuries later we can see the importance of Hamilton’s story beyond the transgression.

Henry Fielding’s pamphlet was entertainment for audiences of the time, but it helped to do more than what he or Hamilton could have ever imagined by creating lasting evidence of queer history.

Resources for Further Reading

The Female Husband, Or, The Surprising History of Mrs. Mary, Alias Mr. George Hamilton, who was Convicted of Having Married a Young Woman of Wells and Lived with Her as Her Husband: Taken from Her Own Mouth Since Her Confinement, Henry Fielding, 1746

The Female Husband: A Trans History, Jen Manion, 2020, Cambridge University Press

The frontispiece illustration and title page of an 1813 edition of Henry Fielding's publication "The Female Husband."