Why So Many African American Artists Moved to Paris in the 1920s

A ROADSHOW expert in African American art explains the history of this phenomenon among Black artists of the early 20th century.

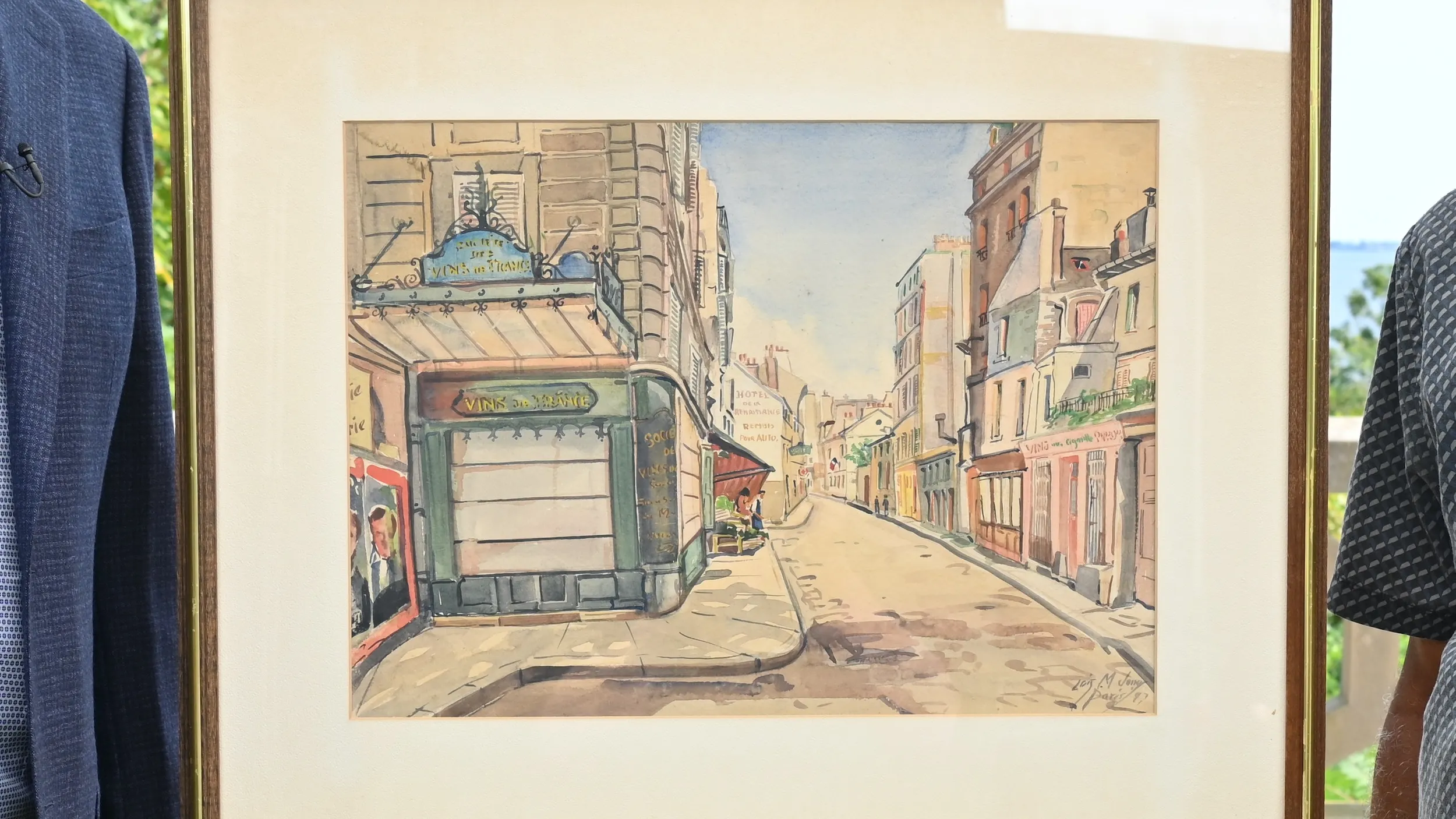

Paintings appraiser Eric Hanks (left) and Laurence (right), a guest at the Sands Point ANTIQUES ROADSHOW in September 2021, discussed this 1947 watercolor titled "Quartier St. Hilaire," by African American artist Loïs Mailou Jones, who, like many Black artists of the time, moved to Paris in the 1920s to enjoy a freer atmosphere in which to practice her art. Hanks estimated the current retail value of Laurence's treasured painting at $25,000.

Jan 31, 2022

BY Eric Hanks

With its beautiful colors and expert use of perspective, seeing Quartier Saint-Hilaire, by the renowned African American artist Loïs Mailou Jones, at the Sands Point ROADSHOW last September was a special treat for me. It’s a beautiful watercolor and a great example of the artist’s special relationship to Paris, a place where she met and was inspired by many important artists like Pablo Picasso and Henry Tanner.

It was particularly rewarding for me to speak with the current owner, Laurence, the artist’s great-nephew, who explained the painting had been a wedding gift to him and his wife from the artist in 1977. His recollections of time spent with his great-aunt shed light on her both as an artist and as a person.

In contrast with the cultural atmosphere in America in the early 20th century, Paris was a place where race didn’t matter much, where Jones felt respected as a person, and was free to develop as an artist and realize her fullest potential. She went to Paris for the first time in 1937. But African American artists had been going there since the 19th century, and by the 1920s were coming there in droves to escape the widespread racial discrimination in the United States and to experience freedom both as artists and individuals.

The institution of slavery in the United States, and its eventual aftermath, created an oppressive atmosphere of degradation and discrimination for persons of African descent. This was felt across all walks of life, including in the visual arts. In 1867, for example, the New York Herald wrote, “…the Negro seems to have an appreciation of art while being manifestly unable to produce it.”

Admission to art schools and academies was difficult and in many cases impossible. Museum exhibitions and commercial gallery representation was almost non-existent. The contributions and accomplishments of African American artists went largely unnoticed in every major art history book and college-level course on art in America.

There are, however, notable exceptions that deserve recognition. In 1869 Charles Ethan Porter was probably the first African American artist to attend the National Academy of Design in New York. Many residents of his native Hartford, Connecticut, helped him develop as an artist, including Harriet Beecher Stowe and Mark Twain. In fact, Twain wrote a letter of introduction that helped Porter during his trip to Paris to study art. And Frederick Church, the great landscape painter, endorsed Porter by purchasing his work and making favorable remarks.

Edward M. Bannister was supported by the mainstream arts communities in Boston and in Providence, Rhode Island. He became an original board member of the Rhode Island School of Design and helped form the Providence Art Club.

In 1880 Henry O. Tanner, with the help of famed artist and art instructor Thomas Eakins, was admitted into the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

In this case, however, things turned ugly when Tanner was dragged from the school by fellow art students onto a street in Philadelphia and tied to his easel with a sign attached to his body that used a racist epithet to mock him and that stated further that there had never been a great Negro or Jewish artist. Tanner left the school and eventually settled in Paris. (He lived in Paris until he died in 1937, the same year Loïs Jones arrived there. He’s buried at the Cimetière de Sceaux about six miles south of Paris. In 1923 France honored him by making him an honorary Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest honor. And in 1927 Tanner became the first African American artist to be made a full member of the National Academy of Design.)

In the early 1920s a real estate magnate named William Harmon established the Harmon Foundation that helped many aspiring African American artists develop and even go abroad to study in Paris. Loïs M. Jones was among the artists who benefitted from the organization’s efforts.

Still, by the 1920s in America, with lynchings and race riots on the rise, both legal and de facto segregation the prevailing reality, and limited opportunities to grow and develop, there was a mass exodus of Black artists to Paris. While escaping racism and all its negative effects was the main reason for this development, other things motivated the artists as well.

Why Paris? What was so attractive about that destination in particular? For starters, as I noted above, African Americans were generally treated with respect and their race wasn’t seen as a sign of inferiority. For many artists that fact alone contributed greatly to their development as artists.

Another major factor was that in the 1920s Paris was the creative center of most of the world, and the city attracted a variety of authors, composers, visual artists and dancers of almost every race and ethnic background from around the world. Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso, Igor Stravinsky, James Joyce, Josephine Baker, Henry Tanner, and others either lived or spent a great deal of time there.

An entire sector of Montmarte, the famous arts district in Paris, became home to many expatriate African American artists. That area was also known for its many jazz clubs and cabarets, such as the Moulin Rouge and Le Grand Duc. Josephine Baker performed in Montmarte often. African American culture thrived. In fact, so stark was the contrast between the atmosphere of the U.S. and that of Paris in the 1920s, despite the effort and expense of the journey, for many African American artists the decision to move to Paris was easy.

Loïs Mailou Jones painted this watercolor in 1947 in Paris, where she had moved from Boston to live and work more freely as an artist 10 years prior.