|

It took five years, over $5 million, and the expertise of hundreds of people,

but our country's oldest official documents—the Declaration of

Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights—are now safely

housed inside the most technologically advanced picture frames in the world.

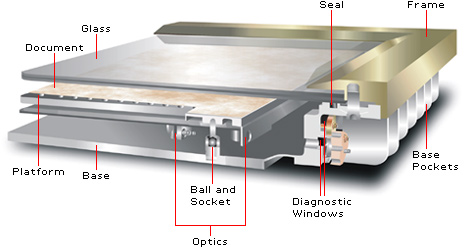

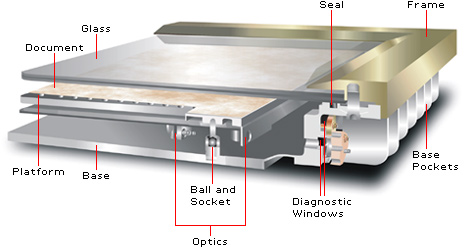

Click on the cutaway illustration below to explore the components of the

Charters of Freedom encasements.—Lexi Krock

|

Glass

The 3/8-inch-thick glass window on the surface of each encasement has two jobs:

to protect the documents inside and to allow visitors the clearest possible

view of them. Each case's glass cover is a two-layer, heat-tempered sheet

capable of withstanding variations in barometric pressure and temperature, and

has a light-reflective coating that eliminates glare from the lighting in the

Rotunda of the National Archives, where the Charters are on permanent display.

|

|

Platform

A lightweight aluminum platform supports a layer of celluloid paper and each

Charters document. The documents are all slightly different in size and none is

perfectly square, so each has its own specially machined aluminum platform. The

platform is perforated with about 4,000 holes, which provide moisture transfer

between the document and the environment inside the case. The documents are

held lightly onto the platform with small plastic clips that viewers can see

when looking into the encasements.

|

|

Base

The builders of the encasements crafted their bases by machining away most of

the material from which they're made, starting with blocks of aluminum about 40

inches square, three inches thick, and weighing more than 500 pounds each. The

end result looks like a large cake pan. The base's inside surface is anodized

in jet black, which gives viewers the impression that the Charters are floating

in midair.

|

|

Document

Each of the Charters was handwritten with gall ink on parchment. They are

extremely fragile, even within their cases. The documents sit on single sheets

of archival paper made of pure cellulose. The paper absorbs and releases

moisture as necessary, and it creates an opaque background for the

semi-translucent documents, which are otherwise difficult to read. The

environment around the document is maintained at around 67°F with a

humidity level of about 45 percent to prevent the parchment from becoming

brittle. The case is filled with humidified argon, an inert gas that precludes

photo oxidation, the chief cause of fading.

|

|

Optics

An intricate optical system sits beneath the platform on which the document

rests. Its purpose is to facilitate diagnostic tests of conditions inside the

encasements. When special light waves penetrate the case from one of two

diagnostic windows on its side, five mirrors reflect the beam and pass it out

of the second window, where a specially calibrated detector measures its

wavelength and intensity. These readings carry precise information about the

conditions inside the sealed case. Conservators usually monitor oxygen and

water levels, but they can use the optical system to run many other tests as

well.

|

|

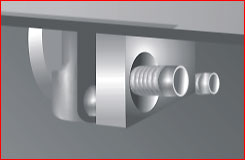

Ball and Socket

A ball-and-socket joint positioned between the platform where the document

rests and the bottom base of the encasement serves to locate and secure the

document platform in place. This joint ensures that the document is completely

immobile even during moving.

|

|

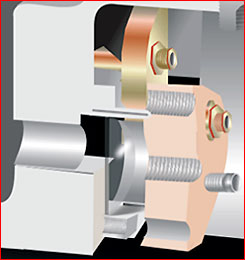

Seal

Experts developed a special vacuum seal between the encasement's base and front

glass to ensure a nearly impervious enclosure for the Charters. The seal is

made of a C-shaped piece of nickel and tin that deforms as the glass is pulled

tightly against the encasement's base, creating a leak-proof barrier.

Conservators' specifications for the ideal environment inside the closed cases

called for no more than 0.5 percent oxygen content—even after 100

years. Laboratory tests indicated that the seal will outperform these specifications.

|

|

Diagnostic windows

Two small windows made of synthetic sapphire are set into the wall of the case's

base. They allow an absorption spectrometer's signal—a beam of light from

a cathode lamp—to pass into and out of the encasement beneath the

document. Readings from the signal help conservators evaluate whether the

humidity and gas content inside is stable. Scientists at the National Institute

of Standards and Technology chose synthetic sapphire for the windows' material

because it does not filter the infrared wavelengths needed to conduct sensitive

readings of the case's interior.

|

|

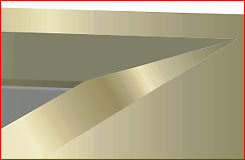

Frame

The titanium picture frame that surrounds each of the seven encasements on

display in the Rotunda of Washington's National Archives is plated with a thin

layer of gold. The frame was designed to be as light as possible yet provide

the strength necessary to hold the glass in place on the base and form an

airtight seal. The frame also provides an aesthetic complement to the grand

décor of the Rotunda, an important component of the Charters

re-encasement project.

|

|

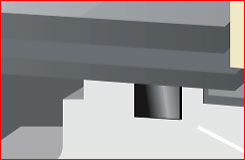

Pockets

To reduce the weight of the encasements and allow for easier moving when

necessary, waffle-like spaces were machined out of the metal wherever possible,

including on the bottom of the base, seen here, and concealed from view between

the bolts beneath the case's outer frame.

|

|

|