Career Milestones

Born the grandson of Alabama slaves during segregation in 1899 and facing a

lifetime of personal and professional challenges, Percy Lavon Julian

nevertheless went on to become one of the 20th century's most influential

scientists. His work with steroids and alkaloids helped bring about a host of

affordable and effective treatments for diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and

glaucoma, benefiting millions worldwide. Here, examine a sampling of this

forgotten chemist's most important scientific and medical

breakthroughs.—Rima Chaddha

|

|

Doctorate by alkaloid (1929-1931)

In 1929, Percy Julian won the opportunity to pursue a dream he had held for

more than a decade: a doctorate in chemistry. Funded by a grant from the

Rockefeller Foundation, he enrolled at the University of Vienna and began work

on alkaloids. His task was to isolate and identify the active ingredient in the

Austrian shrub Corydalis cava, an alkaloid that scientists had found

could soothe pain and calm heart palpitations. This meant breaking the molecule

apart, atom by atom, then deducing its structure—a daunting job at the

time for even the most experienced chemists. Julian succeeded, and in 1931 he

became only the fourth African-American in history to gain a Ph.D. in

chemistry. He returned to the States, ready to launch a career in chemistry (including later, seminal work

using another alkaloid called physostigmine from the calabar bean, left).

|

|

|

Chemical tour de force (1932-1935)

Not long after his return from Vienna, Julian suddenly faced personal and

professional problems that threatened to end his career just as it was

beginning. In characteristically bold fashion, he resolved to take on a

challenge that could save or destroy him as a chemist: synthesizing

physostigmine. This alkaloid proved effective in treating glaucoma, a disease

responsible for 15 percent of all cases of blindness in the United States. Any

scientist who could fully synthesize the alkaloid in a lab would receive

considerable international attention, but pursuing physostigmine was risky.

Leading organic chemist Sir Robert Robinson had already published nine papers

on the alkaloid, and Julian chanced committing professional suicide by

challenging the expert's findings. In the end, Julian and colleague Josef Pikl

proved Robinson in error and completed the synthesis, a coup that many chemists

still marvel at today.

|

|

|

Breaking into industry (1936)

His success with physostigmine led directly to Julian landing the position of

director of research at Chicago's Glidden Company, a stunning achievement given

that most black chemists were all but entirely blocked from industry during the

1930s. In his 17 years at Glidden, Julian would obtain over 100 patents, thanks

mostly to the versatile soybean plant. Using this so-called "miracle bean," he

developed dozens of products, from water-based paints to paper coating to

protein-rich foods, soon generating millions in revenue for the company.

|

|

|

Stigmasterol (1939)

One

of Julian's greatest scientific accomplishments resulted from an accident that

could have cost him his job at Glidden. Water leaked into a tank filled with

$160,000 worth of pure soybean oil, causing the liquid to spoil and a white

sludge to form. Within the sludge, however, lay crystals Julian recognized as

stigmasterol, a plant steroid that could be converted into the pregnancy

hormone progesterone. Doctors prescribed progesterone to women in an attempt to

curb miscarriages, but until Julian's discovery, the drug was simply too costly

for many patients to afford. Although he was not the first to convert

stigmasterol into progesterone, Julian was the first to produce the hormone

affordably and in bulk. Through this achievement and later hormonal research,

Julian helped launch the steroid industry, whose products would eventually

include cortisone and the birth control pill.

|

|

|

"Bean soup" (1942)

Even

as he became a major player in the lucrative human sex hormone game, Julian

continued his work with the soybean. In fact, the soy protein he developed as a

paper coating for Glidden ended up playing a key role in saving lives during

World War II. Glidden had shipped some of Julian's protein to a Pennsylvania

company, which used it to develop a fire-fighting product called Aero-Foam.

During the war, the United States Navy applied the foam to oil and gas fires on

board aircraft carriers and other ships, effectively saving thousands of

sailors from serious injury or death. Affectionately nicknamed "bean soup," Aero-Foam, like later foaming agents, worked by floating

on top of a burning liquid, breaking contact between the flames and the fuel's

surface.

|

|

|

"Wonder Drug" (1949)

Scientists

from Minnesota's Mayo Clinic made headlines in 1949 when they discovered that

the steroid cortisone could ease the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. This

painful disease, which even today affects more than two million Americans,

cripples patients by inflaming their joints and destroying cartilage. But cortisone was extremely scarce, and the sudden demand created by the Mayo Clinic's dramatic announcement drove prices up over $4,000 an ounce—and sent scientists scrambling for new ways to make it.

While many chemists attempted to produce the chemical from scratch, Julian

tried a seemingly simpler approach: synthesizing an almost identical steroid

called Compound S, which needed just one oxygen atom to become cortisone.

Scientists from Michigan's Upjohn Company soon discovered that a common mold

could provide Compound S with the needed atom, eventually making the steroid a

key ingredient in cortisone production, just as Julian had predicted.

|

|

|

Julian Laboratories (1953)

While Julian was conducting his hormonal research in the 1940s, Penn State chemist Russell Marker had discovered an even cheaper source of artificial steroids than the soybean: the Mexican yam. Marker's discovery became the foundation of Syntex, the Mexican company that would eventually overtake Glidden as the leading manufacturer of steroid hormones. In 1953, after Upjohn's discovery of the oxygen-inserting mold, Julian realized that Glidden could still become a leading maker of cortisone—if he could make his Compound S from the Mexican yam. But when he appealed to Glidden's managers to let him open a yam processing plant in Mexico, they turned him down. Risking his career once again, Julian left Glidden in 1953 to form Julian Laboratories and open his own Mexican plant. At Julian Labs, he continued his work in steroids and established a haven for other black chemists, hiring more than any other company in America. Later, he sold his business for $2.3 million, becoming one of the wealthiest black entrepreneurs in the nation.

|

|

|

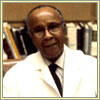

Gaining recognition (1973-present)

In 1973, after more than four decades of chemical research, Julian became only

the second African-American elected to the National Academy of Sciences, one of

the highest honors awarded to scientists in any field. Over time, he received

18 honorary degrees and more than a dozen civic and scientific awards, and in 1993

the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp in his honor. In 1999, the

American Chemical Society recognized Julian's synthesis of the glaucoma drug

physostigmine as one of the top 25 achievements in the history of American

chemistry, a true testament to the importance of his work.

|

|

We recommend you visit the interactive version. The text to the left is provided for printing purposes.

|