|

|

|

by Stephen Lyons "Many a man has been hanged on less evidence than there is for the Loch Ness Monster."When the Romans first came to northern Scotland in the first century A.D., they found the Highlands occupied by fierce, tattoo-covered tribes they called the Picts, or painted people. From the carved, standing stones still found in the region around Loch Ness, it is clear the Picts were fascinated by animals, and careful to render them with great fidelity. All the animals depicted on the Pictish stones are lifelike and easily recognizable—all but one. The exception is a strange beast with an elongated beak or muzzle, a head locket or spout, and flippers instead of feet. Described by some scholars as a swimming elephant, the Pictish beast is the earliest known evidence for an idea that has held sway in the Scottish Highlands for at least 1,500 years—that Loch Ness is home to a mysterious aquatic animal. In Scottish folklore, large animals have been associated with many bodies of water, from small streams to the largest lakes, often labeled Loch-na-Beistie on old maps. These water-horses, or water-kelpies, are said to have magical powers and malevolent intentions. According to one version of the legend, the water-horse lures small children into the water by offering them rides on its back. Once the children are aboard, their hands become stuck to the beast and they are dragged to a watery death, their livers washing ashore the following day. The earliest written reference linking such creatures to Loch Ness is in the biography of Saint Columba, the man credited with introducing Christianity to Scotland. In A.D. 565, according to this account, Columba was on his way to visit a Pictish king when he stopped along the shore of Loch Ness. Seeing a large beast about to attack a man who was swimming in the lake, Columba raised his hand, invoking the name of God and commanding the monster to "go back with all speed." The beast complied, and the swimmer was saved. When Nicholas Witchell, a future BBC correspondent, researched the history of the legend for his 1974 book The Loch Ness Story, he found about a dozen pre-20th-century references to large animals in Loch Ness, gradually shifting in character from these clearly mythical accounts to something more like eyewitness descriptions.

Public interest built gradually during the spring of 1933, then picked up sharply after a couple reported seeing one of the creatures on land, lumbering across the shore road. By October, several London newspapers had sent correspondents to Scotland, and radio programs were being interrupted to bring listeners the latest news from the loch. A British circus offered a reward of £20,000 for the capture of the beast. Hundreds of boy scouts and outdoorsmen arrived, some venturing out in small boats, others setting up deck chairs and waiting expectantly for the monster to appear.

The bubble burst in early January, when museum zoologists announced that the footprints were those of a hippopotamus. They had been made with a stuffed hippo foot—the base of an umbrella stand or ashtray. It wasn't clear whether Wetherell was the perpetrator of the hoax or its gullible victim. Either way, the incident tainted the image of the Loch Ness Monster and discouraged serious investigation of the phenomenon. For the next three decades, most scientists scornfully dismissed reports of strange animals in the loch. Those sightings that weren't outright hoaxes, they said, were the result of optical illusions caused by boat wakes, wind slicks, floating logs, otters, ducks, or swimming deer. Saw Something, They Did Nevertheless, eyewitnesses continued to come forward with accounts of their sightings—more than 4,000 of them, according to Witchell's estimate. Most of the witnesses described a large creature with one or more humps protruding above the surface like the hull of an upturned boat. Others reported seeing a long neck or flippers. What was most remarkable, however, was that many of the eyewitnesses were sober, level-headed people: lawyers and priests, scientists and school teachers, policemen and fishermen—even a Nobel Prize winner. Continue Fantastic Creatures | Birth of a Legend Eyewitness Accounts | Experimenting with Sonar Resources | Transcript | Site Map | Loch Ness Home Editor's Picks | Previous Sites | Join Us/E-mail | TV/Web Schedule About NOVA | Teachers | Site Map | Shop | Jobs | Search | To print PBS Online | NOVA Online | WGBH © | Updated November 2000 |

Carvings of this unidentified animal, made by the ancient

inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands some 1,500 years ago, are the earliest evidence that Loch Ness harbors a strange aquatic creature.

Carvings of this unidentified animal, made by the ancient

inhabitants of the Scottish Highlands some 1,500 years ago, are the earliest evidence that Loch Ness harbors a strange aquatic creature.

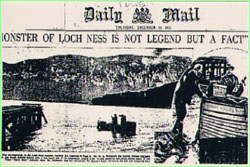

The Loch Ness Monster has been headline news all over the world for more than 60 years.

The Loch Ness Monster has been headline news all over the world for more than 60 years.

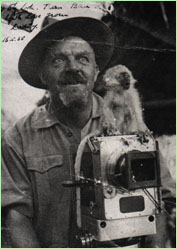

Big-game hunter Marmaduke Wetherell

Big-game hunter Marmaduke Wetherell