|

|

Great Escapes

by Lexi Krock

The myriad escape attempts at Colditz Castle (see Escaping Colditz) had a

long pedigree. Throughout history, prisoners of all sorts have gone to

unheard-of lengths to free themselves from confinement, whether it be house

arrest in Tibet or a life sentence in Alcatraz. Most have failed, but a

significant minority has tasted freedom through patience, skill, and, in many

cases, sheer dumb luck. Here, relive some of the greatest jailbreaks of all

time.

|

A 16th-century portrait of

Mary, Queen of Scots

|

Mary, Queen of Scots (Scotland)

When

Mary, Queen of Scots arrived in Scotland in 1561 from France, where she had

been raised in exile, she expected eventually to assume the throne that was her

birthright. But in 1567, during a rebellion of Scottish nobles, she was

imprisoned in remote Lochleven Castle. Though Mary begged in letters to Queen

Elizabeth and the Queen of France for help in getting free, she was unable to

interest anyone in her cause. Before long, she began plotting her escape.

In her first attempt in March 1568, Mary disguised herself as a laundress and

tried to escape from the castle by boat. But when the boatmen she attempted to

hire noticed her pristine hands and beautiful face, her identity was revealed

and her plan foiled (though remarkably, she did manage to return to her cell

without the castle's guards learning of her ploy). Determined to succeed, Mary

fled the prison again on May 2, 1568. With the help of an orphan she befriended

at the castle, she was able to get out of the castle, across by boat to the

mainland, and successfully away on a horse stolen from her captors'

stables.

Tower of London (England)

The Tower of London has served as a royal palace, arsenal, royal mint,

menagerie, and public records office. But its best-known role, which lasted for

850 years, was as a dark, dank, and bone-numbingly cold political prison. Dozens

of accused spies, traitors, and prisoners of war imprisoned therein made bids

for freedom over the centuries, and a lucky and wily few succeeded.

The Tower of London is now a museum.

The Tower of London is now a museum.

|

|

In 1597, a Jesuit priest named John Gerard made a hair-raising escape. After

hacking away at the stones around the door to his cell, Gerard sneaked past the

guards in the corridors one night and reached a high wall overlooking the moat.

Down below, a boat he had arranged through a sympathetic prison warden waited in

the darkness. The boatmen tossed him a rope, which Gerard tied to a nearby

cannon. When he received a signal that his accomplices had tied off the other

end of the rope across the moat, Gerard slid down the rope to freedom. He was

never recaptured.

The Earl of Nithsdale, who was jailed in the Tower in 1715 for his role in the

Jacobite Rebellion, made a less physically demanding exit. During a visit by

his wife and her three ladies-in-waiting, Nithsdale donned the clothes of one

of the ladies-in-waiting, a Mrs. Mills, and simply walked out with the other

three. (Mrs. Mills, now wearing another set of clothes she had brought with

her, left separately before the alarm was raised.) Safely away from the Tower,

Nithsdale bribed a boatman to carry him and his wife out of the country; they

eventually settled in Rome.

The final escape in the Tower of London's reign as a prison revealed security

so lax it is perhaps best that the Tower soon thereafter became a British

national monument and museum. A British soldier taken into custody during World

War I for writing phony checks became bored one night, even though he was

allowed as many visitors to his cell as he wanted. Leaving his unlocked cell,

he made his way past the guards by nonchalantly strolling past them wrapped in

an overcoat. They took him to be just another visitor, and he headed out for

some nighttime fun in central London. Curiously, he returned to the Tower later

that night and attempted to reimprison himself.

Giacomo Casanova (Italy)

In 1755, Giacomo Casanova was sentenced to five years in Venice's famously

forbidding prison, "the Leads," for repeatedly committing adultery. A

determined escape artist in both marriage and prison, Casanova began plotting

his exit not long after he arrived at the Leads, which was named for the lead

that coated its walls and roof. As he later put it, "it has always been my

opinion that when a man sets himself determinedly to do something and thinks of

nought but his design, he must succeed despite all the difficulties in his

path..."

|

Venice's picturesque Bridge of Sighs connects the Palazzo Ducale (left) and the erstwhile Leads prison (right).

|

Casanova found an iron rod in the prison yard and fashioned it into a digging

tool. For several months, he secretly worked on a tunnel that would take

him out of his cell. His hopes were dashed, however, when he was suddenly

forced to move to another cell. Realizing the guards would carefully watch him

in his new cell, Casanova gave his iron tool, which he had managed to retain,

to the prisoner in the next cell, a monk named Balbi, and begged him to dig one

tunnel joining their cells and another between the monk's cell and the outside.

Balbi agreed, and when he had completed the tunnels, both prisoners crawled out

of Balbi's cell and managed to escape from the Leads using the iron tool to

force open doors and gates in their way. Once they arrived in central Venice,

Balbi and Casanova split up. The police searched for them everywhere to no

avail.

Henry "Box" Brown (North Carolina)

Escape stories abound about runaway slaves, many of whom used the Underground

Railroad to reach the freedom of the North. Less common are stories about

slaves who successfully escaped on their own. One of the most audacious escapes

was that of Henry Brown, who was born as a slave in 1816. After his owner

suddenly sold Brown's wife and children to a new owner in another state,

Brown made an agonizing solo escape to freedom on March 19, 1849.

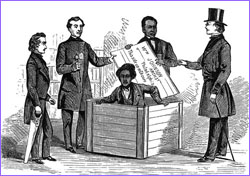

Henry "Box" Brown rises out of a shipping crate amid men from

the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.

|

|

Brown had a sympathetic carpenter build a box three feet long and two feet

wide. After writing "right side up with care" on the outside of the box, two

friends mailed the box, with him squeezed inside of it, from North Carolina to

the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. The journey lasted over

27 hours. Brown had water and ventilation holes, but for several hours, despite

the box's label, he remained upside down. He made it, however, and later became

an active member in Philadelphia's abolitionist community.

Continue: William F. Cody

Escaping Colditz |

The Jailor's Story |

Great Escapes |

The Colditz Glider

Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Nazi Prison Escape Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated January 2001

|

|

|