|

|

Netherlands: Problem

This image could have been taken in Katrina's wake, but it was actually

captured more than a decade ago and an ocean away from Louisiana. Periodic

flooding has plagued the Netherlands since the Middle Ages. Half the country,

including Amsterdam and Rotterdam, lies below sea level in a drainage basin for

three rivers and at the door of the North Sea. A catastrophic flood in 1953

killed nearly 2,000 people and destroyed whole villages; afterward, the Dutch

vowed never again.

|

|

|

Netherlands: Solution

Dutch engineers finally completed their country's sophisticated flood defenses

in 1997. The result is an $8 billion system of enormous, computer-operated dams

and sea surge barriers. The system is admired around the world as an engineering marvel.

The floodgates, parts of which are seen here, remain open ordinarily, allowing

river water to flow into the sea, but they are quickly lowered during storms.

Built to withstand the kind of tremendous flood estimated to occur only once in

10,000 years, the gates have so far done their job successfully.

|

|

|

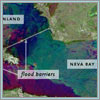

St. Petersburg: Problem

St. Petersburg, Russia is one of the most fabled of waterlogged cities. Its

battles with flooding have been immortalized for centuries in Russian art (such

as in this painting) and in literature. The city was built atop a swamp fed by the

Neva River and the Gulf of Finland. Each fall and winter, strong winds and ice

block the flow of the Neva into the Gulf, causing the river level to rise and,

at least once a year, spill excess water into the city. Over the years, several

disastrous floods, including the two largest in 1824 and 1924, have left

considerable death and destruction in their wake.

|

|

|

St. Petersburg: Solution

In 1980, the Soviet government began to erect a pair of massive storm surge barriers on either side of a small island

in the Neva. With the project nearly 65 percent complete, financial problems and environmental

concerns brought it to halt less than 10 years later. But in 2003, with new foreign funding and

a plan to keep the river healthy, the project was revived. Construction is now under way to

finish the barriers, seen here, which will shut during storms and hopefully spare St. Petersburg

any more high-water floods.

|

|

|

London: Problem

Londoners are characteristically blasé about their flood-prone city, but

the tidal Thames River, which carves through its center, has a history of

severe flooding. The threat of high tides has increased over time due to a slow

but continuous overall rise in the river's water level, which experts attribute

to climate change and the gradual settling of the city.

|

|

|

London: Solution

In the 1970s, the so-called Thames Barrier, seen here, was built across the

river to protect London from the kind of disastrous flooding that last occurred

there in 1953 (when Holland also flooded) and took over 300 lives. But

scientists say that the defense the barrier provides is gradually declining,

and it may not be able to continue to block rising tides past the year 2030.

Officials have charged a commission with finding a longer-lasting solution, and

a proposal is under consideration to build a more extensive, 10-mile gated

barrier along the Thames.

|

|

|

Venice: Problem

Venetian scenes like this one have become almost as representative of the city

as its gondolas and elegant architecture. The ground on which Venice lies is

famously sinking. This, combined with rising sea levels and periodic storms

that cause the Adriatic Sea to flood Venice's lagoon, creates a phenomenon

known as acqua alta, or high water—in other words, flooding.

Venetians have dealt with the rising water for centuries by raising the level

of floors in buildings and the pavement along city canals, but powerful storms

can still prove destructive.

|

|

|

Venice: Solution

This mobile flood barrier embodies the most substantial engineering aspect of

the proposed solution to flooding in Venice. It is part of a

multibillion-dollar series of 78 metal gates that will rise off the seafloor at

the three entrances to Venice's lagoon whenever acqua alta is forecast,

blocking the Adriatic until high tides subside. This project has been

controversial, with many experts concerned for the environmental health of the

lagoon and advising against what may be only a relatively short-term solution.

But the gates are slated to be completed in 2011.

|

|

|

San Antonio: Problem

Texas is one of America's most flood-vulnerable states. Severe rains can cause

water to rise across dozens of counties quickly and simultaneously, destroying

homes and highways and threatening the downtown areas of major cities such as

Houston and San Antonio. In 2002, as much as two feet of rain fell on

southeastern Texas in a week, flooding three major river systems along the Gulf

of Mexico and inundating highways such as this one outside of Houston.

|

|

|

San Antonio: Solution

Experts consider San Antonio's anti-flood approach among the most innovative

solutions to flooding in any metropolitan area. Between 1987 and 1996, federal

and local governments funded the construction of a 16,200-foot concrete

flood-diversion tunnel beneath the city. It siphons rainfall out of populated

areas and carries it to the San Antonio River. Fully 24 feet in diameter, the

tunnel was dug with a massive tunnel-boring machine, seen here in action

beneath San Antonio.

|

|

|

New Orleans: Problem

Immediately after Katrina—and even before—officials began

brainstorming new flood protection infrastructure. Tailor-made for New Orleans,

it would replace or bolster the city's existing levees. It's still

too soon to know what the plan will be, but in hundreds of television

appearances, radio interviews, lectures, op-ed articles, and scientific papers,

the experts have weighed in with a wide range of ideas, from aggressively

restoring Louisiana's naturally defensive delta and saltwater marshes, to

mobile floodgates, to high-tech, electronically sensitive levees.

|

|

|

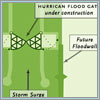

New Orleans: Solution

One new idea for New Orleans was already in development before Katrina.

Construction has begun on a sophisticated hurricane floodgate that would close

across the Harvey Canal in the event of a storm surge. The $36 million

floodgate will protect 250,000 people in the West Bank area of New Orleans,

which was relatively unscathed by Katrina, from another storm. When the new

barriers are finished, they will be the first hurricane-specific canal barriers

of their kind in New Orleans and most likely the first new flood proofing in

the city since Katrina.

|

|

|