|

A 300-Year Struggle

|  |

|

|

Storm That Drowned a City homepage

|

| |

|

| |

The French explorer

Jean-Baptiste

Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville made a fateful decision in 1717 when he chose the

site for New Orleans along a sharp bend in the Mississippi River. Bienville

selected the site against the objections of his chief engineer, who realized

that the area suffered from periodic floods. New Orleanians have been paying

the price of Bienville's insistence ever since, from the first major flood

shortly after the town's founding to the merciless juggernaut that was

Hurricane Katrina. Here, follow the historical trajectory of New Orleans'

ever-worsening struggle to keep out water.—Peter

Tyson

| |

|

| |

A French foothold

1708

A Frenchman visiting the Mississippi River near what would become New Orleans

writes, "This last summer I examined better than I had yet done all the lands

in the vicinity of this river. I did not find any at all that are not flooded

in the spring. I do not see how settlers can be placed on this river."

1717

The French establish "Nouvelle-Orleans" on the site of an erstwhile

Quinnipissas Indian village. (Indians first occupied sites in eastern New

Orleans around 500 B.C.) Like the Quinnipissas, the French select the site

because it's the highest and driest spot for several miles around. Within a few

years slaves are put to work clearing land on the natural levee the French have

selected for the town.

1721

Surveyors lay down a grid pattern of streets of some 40 blocks, with drainage

ditches around each block and a dirt palisade surrounding the town. A

never-ending battle against high water—both floodwaters and high water

tables—has begun.

1722

Construction starts on a four-foot-high earthen levee (from the French word lever,

"to raise"), the beginning of three centuries of combating high water through embankments. By 1726, the levee remains

incomplete, though a section fully 18 feet tall stands before the Place d'Armes

(now Jackson Square) in the heart of the nascent town.

1732

After New Orleans floods in 1731, the town's Superior Council mandates that all

settlers along the river nearby build levees. By 1732, earth-and-timber

embankments reach from 12 miles south of New Orleans to 30 miles north on both

sides of the Mississippi.

1752

Floods in the town remain troublesome throughout the 1740s, as city engineers

build their levees ever higher to cope with increased flood levels brought on

by changes in the landscape upriver. By 1752, landowners have added another 10

miles of levees beyond their 1732 extent.

| |

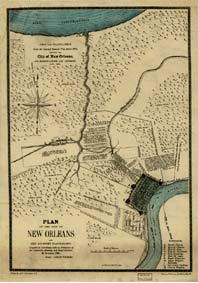

In this 1875 copy of a 1798 map of New Orleans, one

can roughly gauge the width of levees the French built along Bayou Metarie

(center left) and Bayou Gentilly (upper right) by the extent of land on either

side of the bayous that is not marked by tree symbols.

| |

|

| |

Into American hands

1803

With the Louisiana Purchase, President Thomas Jefferson acquires New Orleans

and an additional 828,000 square miles of land in the south-central U.S. from

Napoleon Bonaparte. The purchase price: $15 million.

1811

The first steamship arrives in New Orleans. The town begins to grow as an

important trading center, serving as a critical link between the world's oceans

and 19,000 miles of river along 31 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces.

1816

After a nearly month-long flood this year drives many poorer New Orleanians from

their homes, Edward Fenner, a noted New Orleans medical authority, writes,

"should not those in affluent circumstances come to the aid of their less

fortunate fellow citizens, great indeed, we fear, will be the distress of the latter,

from poverty, famine, and perhaps pestilence."

1828

Another flood in New Orleans produces the highest water recorded up to the

time. The deluge sparks a renewed bulwark-building campaign. Laws are now in

place both regulating the dimensions and maintenance of levees and mandating a

tax to pay for their construction.

1846

Louisiana State engineer P. O. Hebert warns that New Orleans is in "imminent danger

of indundation" annually: "Every day, levees are extended higher and higher up the

river—natural outlets closed—and every day the danger to the city of

New Orleans and to all the lower country is increased. Who can calculate the loss

by an overflow to the city of New Orleans alone?"

1849

Two topographic engineers describe the flood of 1849 as the most destructive

flood known. A breach in the levee on the east bank of the Mississippi 18 miles

above New Orleans does an "immense amount of damage," they write, inundating

the city for 48 days. Another flood the following year convinces the federal

government to grant monies to build a continuous levee system.

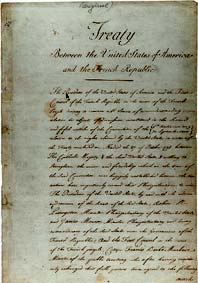

| |

The Louisiana Purchase Treaty secured

the present-day states of Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Iowa,

Nebraska, and North and South Dakota.

| |

|

| |

The levees-only policy

1850

By mid-century, city engineers agree that the best way to control the

Mississippi is to force it to flow down a single channel with large levees on

either side. The river will of necessity scour out a deeper channel for itself,

reducing the flood threat, they believe. This becomes policy until 1927, when a

disastrous flood in New Orleans proves the folly of the policy.

1874

Four times between 1849 and 1874, a breach occurs in the Mississippi River

levee at Bonnet Carré north of New Orleans, each time sending a flood

towards the city at an estimated rate of 150,000 cubic feet per second. One

commentator writes that floodwaters swept away "dwellings, sugar-houses, crops,

and fences, like chaff before the wind," and even threatened the safety of the

city itself.

1882

The worst flood in the Mississippi River up until this time opens more than 200

breaches in the river's levees, most of them in Louisiana, and keeps New

Orleans at flood stage for 91 days. One writer says this flood "left the people

of the valley prostrate."

1883

In Life on the Mississippi, published this year, Mark Twain scoffs at the

Mississippi

River Commission's flood-control mission, writing that "One who knows the

Mississippi will promptly aver ... that ten thousand River Commissions ...

cannot tame that lawless stream ... cannot bar its path with an obstruction

which it will not tear down, dance over, and laugh at."

1893

A day-long assault of 30-foot waves overtops coastal levees and destroys a

fishing village south of New Orleans, killing 1,500 people.

1920

New Orleans is now the 14th-largest U.S. city, with a population approaching

400,000. Improvements in drainage technology, foremost among them a new screw

pump invented by engineer Albert Baldwin Wood, enable the city to start

expanding northward toward Lake Pontchartrain in the 1920s.

1923

The Army Corps of Engineers finishes connecting New Orleans to the Gulf

Intracoastal Waterway, a 1,300-mile canal stretching from Texas to Florida.

During Hurricane Katrina in 2005, this waterway will unfortunately provide a

direct route for storm surge into eastern New Orleans.

1927

On April 29, with dangerously rising floodwaters in the Mississippi threatening to

overwhelm New Orleans, Louisiana's governor orders the Army Corps of Engineers

to dynamite a levee along St. Bernard Parish, allowing floodwaters to drain

across the parish's rural neighborhoods and wetlands to Lake Borgne and the

Gulf of Mexico. New Orleans proper is saved, but the parish is devastated. More

than 200 people die and 700,000 are left homeless. The disaster marks the end

of the levees-only policy; as one writer puts it, "a policy had been breached

and the pouring waters were sweeping an era away."

| |

Workers strengthen a levee in the Third

District, 1900.

| |

|

| |

Spillways and sprawl

1928

Congress acts swiftly to address the flood-control problem, passing the 1928

Flood Control Act. Ostensibly the act says that the Mississippi cannot be

managed by levees alone, but also requires spillways and reservoirs. The act

authorizes the building of a spillway at Bonnet Carré near Lake

Pontchartrain to shunt floodwaters away from New Orleans and into undeveloped

areas.

1930

The wetlands between New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain, which provide habitat

for wildlife, trapping and other livelihoods for residents, and, perhaps most

importantly, hurricane protection, continue to disappear as the government

drains them and people build homes there. Marsh loss in southern Louisiana will

reach 35 square miles a year or more over the coming decades, a rate that by

the time Katrina hits in 2005 will have a severe impact.

1936

The 7,000-foot-long Bonnet Carré spillway is finally completed. It

includes 350 openings, each bearing 20 timber planks that can be individually

removed to increase flow out of the spillway. Within a year it earns its keep,

protecting New Orleans from the flood of 1937 by sending floodwaters across a

narrow strip of land into Lake Pontchartrain. The spillway will successfully do the same

seven more times over the next 60 years.

1963

Corps engineers complete the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet, a 76-mile canal

that offers a direct route for ships between New Orleans and the Gulf of

Mexico, saving valuable time over traveling up and down the sinuous

Mississippi. But like the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, the canal also serves as

a highway to New Orleans for hurricanes and their storm surges.

| |

During a flood, workers can remove individual

timbers and place them atop the Bonnet Carré Spillway, allowing for very

precise release of floodwaters.

| |

|

| |

Hurricane season

1965

Hurricane Betsy sideswipes New Orleans, killing several dozen and becoming the

first storm to cause more than $1 billion in damage. Four parishes sustain

significant flooding. "God, it was like one giant swimming pool as far as the

eye could see," one resident of Chalmette recalled. "A woman who lives down the

block floated past me, with her two children beside her."

1969

From 1559 to 1969, 160 recorded hurricanes struck Louisiana, an average of one

hurricane every two and a half years. With the state's and New Orleans'

vulnerability to hurricanes in mind, as exemplified by Betsy, the Army Corps of

Engineers in the 1960s develops its first hurricane-protection plan for the

city and state.

1973

In April, the worst flood since 1927 hits the city. More than two dozen people

die, and damage is estimated at $427 million. But the levees hold, preventing a

much greater catastrophe. For the first time in history, a major flood has been

diverted successfully to the sea.

1985

In response to Hurricane Betsy 20 years earlier, city engineers finally approve

hurricane-protection projects along the New Orleans lakefront and in St.

Bernard Parish. The projects include strengthened seawalls and levees along the

lakefront as well as within the Industrial Canal and along the Mississippi

River-Gulf Outlet. The projects are 80 percent complete by 1994.

| |

Hurricane Betsy flooded 164,000 homes when she swept through the New Orleans area in September 1965.

| |

|

| |

Modern times

1988

New Orleans becomes America's number-one seaport in total tonnage handled.

1995

Twenty inches of rain fall in a single day, causing seven deaths and $1 billion

in damage across three parishes. With an average rainfall of 58 inches, New

Orleans is one of the rainiest cities in the U.S. And with the city having expanded into

numerous low-lying areas, it has become extremely vulnerable to floods not just

from the river and hurricanes but from its own protracted rainy season.

2001

Improved protection along the London Avenue, Orleans Avenue, and 17th Street

Canals in Orleans Parish is 90 percent complete. The improvements include

lining the three canals with "I" walls and building 10 flood-proof bridges

where roads cross the canals. New Orleans, it is thought, is now well prepared to withstand a

Category 3 storm.

2005

Hurricane Katrina, a Category 4 storm when it makes landfall on August 29,

precipitates the greatest natural disaster in U.S. history, killing more than

1,000 people, leaving 100,000 homeless, and causing damage in the hundreds of

billions of dollars. Most of New Orleans is underwater as overtoppings and

breaches occur in the 17th Street, London, and Industrial canals as well as

along the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet. (For

more details, see How New Orleans Flooded.)

| |

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, New

Orleans' Superdome served for countless displaced residents as an island in a sea of inundation.

| |

|

| |

Further Reading

Transforming New Orleans and Its Environs: Centuries of Change

Craig E. Colten, editor. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2000

Land's End: A History of the New Orleans District, U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers, and Its Lifelong Battle With the Lower Mississippi and Other Rivers

Wending Their Way to the Sea

by Albert E. Cowdrey. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers New Orleans District, 1977

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|