We recommend you visit the interactive version. The text to the right is provided for printing purposes.

|

|

|

Dung

When it comes to figuring out all you can about an extinct mammoth and its world from its remains, there's nothing quite like a good piece of poop. It may not look like much to you or me, but to a paleoecologist it's a priceless gem. Such a specialist can hardly wait to get his hands on it, to ferret out all its long-held secrets. In this feature, have a look at all the primeval goodies that scientists have teased from the dung at left, and what those leftovers have revealed about the mammoth as well as its diet, habitat, even the climate in which it lived 22,000 years ago.

|

|

|

Mammoth

The dung was packed within the intestine of this frozen woolly mammoth. It is known as the Yukagir mammoth for the Siberian village near where it was found in 2002. The mammoth's permafrost tomb preserved its head, tusks, front legs, and parts of its stomach and intestinal tract. From its bones and enormous tusks, the scientists who rushed to the site (including mammoth experts Dick Mol, left, and Larry Agenbroad) guessed that the mammoth was an old male that when alive stood over nine feet tall at the shoulder and weighed four to five tons. From the dung ball, they learned heaps more.

|

|

|

Grass

The main component of the Yukagir's final meal was grass, including these stems from the Poaceae family. Remarkably, like many of the dung's floral remains, the stems have retained their color and shape ever since the mammoth tore them from the tundra roughly 22,500 years ago. (Radiocarbon dating supplied his estimated age.) Earlier studies had shown that grasses, sedges, and rushes comprised the bulk of the diet of Siberian woolly mammoths during the Pleistocene ice ages, so this discovery came as no surprise. But this was only the most obvious finding.

|

|

|

Seeds

The stool held grass seeds as well, including this seed from a species identified as Poa cf. arctica. (The "cf." means "confer" and indicates that the primordial species resembles a still-living species but is not confirmed to be the same.) To identify such "macrofossils," or visible parts, the international team that analyzed the dung boiled bits of poop, sieved the remains, floated them in a petri dish full of water, and studied them under a stereomicroscope. Such seeds and other floral bits enabled them to "flesh out" the mammoth's ice-age environment.

|

|

|

Moss

For microfossils and other largely invisible stuff, the team relied on methods with mouthful names like thermally assisted hydrolysis and polymerase-chain-reaction amplification. One such tiny ingredient in the poop was mineral dust (seen here, in gray, coating a piece of moss). Wind would have lifted this dust from eroded patches of ground and covered plants with it; when the mammoth ate the plants, he took in these minerals as well. The presence in the giant's gut of mosses such as this one showed that his surroundings were not all dry grassland; moist areas existed there as well.

|

|

|

Twigs

Another sizeable portion of the mammoth's last supper was willow. These were not the big, bushy willow trees common in temperate areas today. Rather, the stems at left came from a small-leaved dwarf species known as Salix cf. arctica. The twigs had been broken but not digested, leaving the scientists wondering whether the mammoth could possibly have absorbed sufficient nutrients from his food. The lack of attached leaf stalks on the twigs also led them to infer that he had died between two growing seasons.

|

|

|

Leaves

The dung offered up willow leaves as well (left). All were badly preserved, and none of them was connected to a twig—further evidence that the mammoth had perished between growing seasons. The team thinks, in fact, that the Yukagir mammoth may have eaten and partially digested dead leaves. Was this because little else was available at the time of his death? Just how harsh was the climate at the time? And what season of the year did he die?

|

|

|

Rings

To help find out, the team sliced thin cross-sections of the willow twigs. The thickest twig was less than a fifth of an inch in diameter, yet it bore more than 20 annual rings. That growth rate is even slower than that of modern Salix arctica, indicating the mammoth's climate was even more austere than that of northern Greenland, where S. arctica lives today. The cross-sections were even clearer as to season of death: When the mammoth ate the willow, the first spring vessels of the outermost rings were just forming—a clear sign that he had died in early spring.

|

|

|

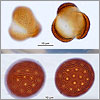

Pollen

Pollen abounded in the dung. The majority of the grains were of wind-dispersed pollen, such as that of Artemisia, a type of sage (top pair). The dung also retained small amounts of insect-carried pollen from a variety of flowering plants, including Polemonium, commonly known as Jacob's ladder (bottom pair). The pollen record was likely influenced by the mammoth's food choices during his final meal, the team notes, and the pollen probably integrates several years of plant growth. But one finding was unequivocal: the total absence of tree pollen. The mammoth's world was treeless.

|

|

|

Landscape

This is the spot where the mammoth was found. Since the area remains treeless today, his home may have looked largely like this. Paleoexperts have given the mammoth's ancient habitat a name, "mammoth steppe." It was a cold, arid plain but with moister meadows here and there. Water was likely available year-round, including snow in winter and streams or standing water in summer. Several plant species identified in the dung, including marsh marigold, require permanent water, and the mammoth certainly drank from freshwater pools, as indicated by the green pond algae found in his stool.

|

|

|

Buds

The absence of any trees in his ecosystem marks a significant change in the usual diet of Siberian woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius). In all other Siberian mammoth dung analyzed to date, scientists have recovered twigs of alder, birch, larch, and spruce. Mammoths nibbled these trees to get nutrients lacking in grass. Since no trees of any kind lived in his neighborhood, the Yukagir mammoth may have consumed the dwarf willow shrubs (including this bud, with nascent leaves visible within) to get vitamins lacking in the meadow grasses.

|

|

|

Dung, Part Two

Still other nutrients came from dung—dung the mammoth ate. Animal droppings may have supplemented his daily intake of grasses and other vegetation (here, a moss spore structure). The team recovered fruit bodies of a dung-inhabiting fungus that only develops at least a week after manure is exposed to air, which the mammoth's own poop never was. The swallowed stool was probably mammoth dung, in fact. Among living mammals, elephants (along with hyraxes and manatees) are unique in having no bile acids—and none were found in the feces of the mammoth, a close relative of the elephant.

|

|

|

Fate

In the end, the team was unable to determine his cause of death. (Here, one of his front legs in situ.) His molars were heavily worn, another possible indication that he was malnourished. The added stress of a severe winter may have sealed his fate. As Dutch scientist Bas van Geel and his 15 coauthors write in the 2008 paper on which this feature is based, "the start of the growing season might have come too late for this animal. Lying down in a sheltered hollow, he died, and became covered with a thick mud layer that ... subsequently froze and preserved part of him."

|

|

|