Megastorm Aftermath

How can cities prepare for rising seas and raging storms? Airing October 9, 2013 at 9 pm on PBS Aired October 9, 2013 on PBS

Program Description

Transcript

Megastorm Aftermath

PBS Airdate: October 9, 2013

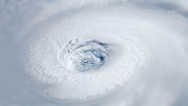

NARRATOR: It is a city's worst nightmare. Megastorm Sandy delivers a wall of water 14 feet highâ¦

MARC MENDE (Metropolitan Transit Authority): There was no way to stop it.

NARRATOR: â¦plowing into New York.

MARC MENDE: You needed Superman, I guess.

NARRATOR: And across the region, crucial services collapse.

DAVID HOLLAND (New York University): This is Manhattan, and it was just chaos.

NARRATOR: Miles of coast line are devastated.

DANIEL F. MUNDY, SR. (Broad Channel, New York): Whatever anybody could do, it was not enough. And who's to say it ain't going to happen again?

NARRATOR: But there is little doubt it will. The planet is heating up, glaciers are melting, sea level is rising.

DAVID HOLLAND: Should warm ocean currents reach these glaciers, all hell could break loose.

NARRATOR: How do we protect ourselves? Can we wall off our cities from the sea? Are some places destined to disappear?

KLAUS JACOB (Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory): Florida is doomed.

NARRATOR: In the wake of Sandy, how will we respond?

STEVEN FLYNN (Northeastern University): This is screaming at us that we need to be better prepared.

NARRATOR: Megastorm Aftermath, right now, on NOVA.

New Yorkers pride themselves on being toughâ¦

MAN ON BOARDWALK: We'll ride it out like we ride all of them out, you know?

NARRATOR: â¦resilient, nonplussed, and maybe a little cocky in the face of adversity.

STREET PERFORMER: It's raining here, but, whatever. It's a little rain. What are you going to do?

NARRATOR: But on October 29th, 2012â¦

SAM CHAMPION (ABC News): This is a record surge of water, rushing over the edge of lower Manhattan.

NARRATOR: â¦they and their city met their match.

MIKE HERZOG: My god, it's washing everything away!

NARRATOR: That was the day Megastorm Sandy came rolling into town.

GINGER LEE (ABC News): The storm is on top of us right now.

NARRATOR: It was the biggest, most devastating storm to hit the city in recorded history.

Strong winds pushed a huge wall of ocean water, 14 feet higher than sea level, onto the coast, covering 51 square miles of the city. Seventy-thousand homes and apartments were damaged; an entire neighborhood burned to the ground; utilities failed in spectacular, massive fashion, and 43 people died here, most of them drowned.

Sandy brought mighty Gotham and much of New Jersey to their knees.

As soon as the waters recede, unsettling questions begin to roll in: Was Sandy a freak event or a window into our future?

We live in a new era. Greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, generated by burning fossil fuels, are building up in our atmosphere, insulating our planet, holding in more of the sun's heat and driving the temperature up. The earth's climate is changing.

No one knows exactly how that will affect our weather day-to-day, but there's one thing scientists agree on, as the earth and its oceans heat up, warm water takes up more volume than cold; at the same time, glaciers are melting. The result? Sea level around the world is rising.

And that means, as the storms come, coastal cities are more and more at risk.

KLAUS JACOB: Climate change will raise the sea level, and sea level will contribute to the power of flooding.

NARRATOR: It's not only New York and New Jersey that are in the crosshairs, but Miami, New Orleans, Charlestonâ¦

J. MARSHALL SHEPHERD (University of Georgia): As our sea level continues to rise, it won't take a Hurricane Andrew- or Katrina-sized storm to create flooding hazards along our coastlines.

NARRATOR: â¦thousands of miles of coastline, all around the world—China, India, Japan.

STEVE FLYNN: We live increasingly in coastal areas. This is screaming at us that we need to be better prepared.

NARRATOR: But what can coastal cities do to prepare and protect themselves? Can we engineer a solution and wall off our cities from the sea, or are some areas just too hard to protect? And, eventually, should they be abandoned?

KLAUS JACOB: We have to start to retreat from the most exposed waterfront.

MICHAEL BLOOMBERG (Mayor, New York City 2001-2013): As New Yorkers, we cannot and will not abandon our waterfront. It's one of our greatest assets.

NARRATOR: Or is there another way, a way to embrace nature's defenses and the water, even as we try to keep it at bay?

STEVE FLYNN: Sandy should demand a national response. There, but for the grace of godâ¦. It could have been Boston, it could have been Seattle, it could happen to Houston, and how we, as a nation are prepared for dealing with these kinds of risks? And reality is we're not near as prepared as we need to be.

NARRATOR: As Sandy approached, Dan Mundy knew his home was at risk. The retired firefighter lives in one of the most flood-prone neighborhoods of New York City, Broad Channel. It's a sliver of an island in the middle of Jamaica Bay, on the southern end of Queens; elevation above sea level: about four feet.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: It's very unique, what we have here. It's very different. People that don't know and come and visit and see it, they say, "Wow! This is beautiful. Look at your views."

NARRATOR: Well aware that his home was in harm's way, Dan Mundy built his own private seawall around it.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: You can see my bulkhead out there. That's 250 tons of stone.

NARRATOR: But the fortress couldn't hold back Sandy's storm surge.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: You see how high it is and how big it is? Well, Sandy come over the top of it. It was just unreal, this storm. It just went beyond whatever anybody could do. It was not enough. And who's to say it ain't going to happen again?

NARRATOR: That's the question haunting thousands, whose homes, like Dan's, were damaged or destroyed by the sea.

Sandy's waves tore through the Rockaways, about five feet above sea level; the Red Hook section of Brooklyn: eight feet; Staten Island: four feet above sea level; Lower Manhattan: about eight feet at the Battery. In New Jersey, Sandy caused flooding from Hoboken to Atlantic City. Around the region and around the world, the question is not if it will happen again, but when and how often?

KLAUS JACOB: We know very well a mean trend where things go; the sea level rise will not go down. We know that for sure.

NARRATOR: What scientists don't know for sure is how fast it will rise. Over the past century, sea level around New York is up about a foot, partly because of subsiding land. But how much will it rise in the next hundred years?

That may depend on what happens here, in Greenland, where vast masses of ice are flowing from land to ocean, raising the sea level. David Holland is trying to crack the sea level mystery. That's what's brought him here, on a hazardous voyage though the iceberg-cluttered waters of Jakobshavn Fjord, in Greenland.

They say the iceberg that sank the Titanic came from this breathtaking and extremely dangerous place.

DAVID HOLLAND: These things roll, and if it rolls, it will take the ship with it.

NARRATOR: Holland is a mathematician, and he's here, because he doesn't have much faith in the numbers.

DAVID HOLLAND: I would say, at this moment, we cannot project future sea level mathematically. We have to be honest with ourselves. We have incomplete knowledge, at the moment, and incomplete data.

NARRATOR: Some of the data we do have is disturbing. An enormous reservoir of freshwater is locked up in the glaciers here, at least for now.

DAVID HOLLAND: If you melted all of Greenland, then local sea level around the planet would rise just over 20 feet.

NARRATOR: Twenty feet would submerge more than a third of the city of New York, but no one is predicting that this will happen anytime soon. The Greenland glaciers have been slowly melting for thousands of years, since the end of the last ice age. But today, with the planet heating up faster, there are ominous signs that the movement of ice from land to sea might be speeding up.

David Holland believes the reason lies, not in the warming air, but in the water. As a glacier slides off the land, its underside comes into contact with the seawater. In 1997, the ocean currents changed abruptly and the water here got warmer by nearly three degrees Fahrenheit. Soon, the glacier started melting much faster.

During the 20th century, it retreated eight miles, but in just the first decade of the 21st century, it receded another nine miles. David Holland is trying to solve the mystery of why this happened and if it could happen again.

DAVID HOLLAND: The main thing we're trying to study is how do warm currents approach ice sheets? Why is it that sometimes we see warm water near ice sheets, sometimes not? The answer to that question is ultimately the answer to future sea level.

I'm going to start the next cast.

NARRATOR: To try to find that answer, he repeatedly sends a probe, brimming with instruments, below the surface to depths of 300 feet and more, testing the water's temperature, oxygen content and salinity, because all this water is not created equal.

The water near the surface is less salty, diluted by the fresh water from the recent glacier melt. Usually, cold water sinks, but not in this case.

DAVID HOLLAND: Fresh water is light, and it floats on top of the ocean.

NARRATOR: Below it is the saltier ocean water that is warmer than the water above it. Holland has found much of it comes from the tropics, carried to Greenland by the Gulf Stream. It eats away at the glacier's underbelly, eventually causing big pieces to break off, making more icebergs, putting more water in the sea.

Holland is determined to discover more about the dynamic between ice and ocean, so he also submerges probes for a year, drops some from helicopters, and even attaches sensors to deep diving seals.

Still, they're just pinpricks of light in a dark void. There is little known about how glaciers move and melt, not just here, in Greenland, but in Antarctica, too.

DAVID HOLLAND: If you melted Antarctica, you would raise global sea level, say, 200 feet.

NARRATOR: Two hundred feet would flood every city on the eastern seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico; the Florida peninsula would be long gone.

DAVID HOLLAND: That's not going to happen tomorrow morning.

NARRATOR: The vast majority of Antarctic ice is stable, but a few ice sheets, in the west, sit on ground below sea level, making them more vulnerable to melting.

In 2002, the Larsen B Ice Shelf, a floating piece of ice the size of Rhode Island, suddenly broke up, allowing the glacier behind it to flow faster into the ocean. David Holland worries it could happen again, to other glaciers, nearby.

DAVID HOLLAND: These areas are enormous and warm water is near. So, should warm ocean currents in the Southern Hemisphere reach to these glaciers, all hell could break loose.

NARRATOR: With so many unknowns, the current official estimate for sea level rise ranges from two to five feet over the next century. But David Holland thinks that if we want to protect coastal cities, we should be prepared for much more.

DAVID HOLLAND: If you were to say to me, "For the next hundred years, I want to be conservative and protect things," then I would build walls three meters, or ten feet.

NARRATOR: When it comes to flood protection, Holland knows firsthand some of the dangers of building too lowâ¦

DAVID HOLLAND: Is it sinking?

NARRATOR: â¦because, when he's not investigating the glaciers of Greenland, he lives here, in the heart of Manhattan.

The night Megastorm Sandy came to town, he and his wife, Denise, were in their apartment.

When Sandy struck, he and his wife Denise were high and dry in their apartment.

And then the lights went out and stayed out for five days. There was no power, no heat, no water.

DAVID HOLLAND: It was surreal: the concept that this major city, Manhattan, with this massive infrastructure, could be brought to its knees by a storm. And it was just chaos.

NARRATOR: The Hollands were among the quarter million New Yorkers who were in the dark because of this spectacular event.

The Consolidated Edison power substation sits at the end of 14th Street, right next to the East River, about six feet above sea level.

ROBERT SCHIMMENTI (Consolidated Edison): Water and electricity does not mix, obviously.

NARRATOR: Most of the electricity for Lower Manhattan flows through these transformers and relays, as long as they're not under water. For over 50 years, the 11-foot-high floodwalls worked just fine, until Sandy's storm surge pushed 14 feet of water over the banks of the East River.

MICHAEL BROWN (Consolidated Edison): We were designed forâ¦our "hundred-year-flood" design was down here, and the waters were coming over this capstan.

NARRATOR: The flash point was a circuit breaker that shorted out after the salt water rushed in.

BOB SCHIMMENTI: That breaker was at a lower elevation. And as the water started to rise, that breaker flashed over and then caused a subsequent failure at the transformer. And so, then, you saw this big flash of light, then there was cascading failure because of the other relays, and then the station ended up being shut down.

NARRATOR: Con Ed is determined to keep this station dry whenever the next megastorm hits. They're building about 180 aluminum doors, to plug any holes in the substation's protective ring.

BOB SCHIMMENTI: So, if the same event occurred and the same storm surge occurred, there'd be no customers out in Manhattan.

NARRATOR: And beneath the sidewalks, all across the city, workers are installing waterproof equipment.

ANTHONY SCARPA: Everything is in this hole, even if you submerge it, is all submergible equipment. If it is under water, it will still operate normally.

NARRATOR: And they're deploying more "smart grid" technology that can be monitored remotely and reduce power outages.

BOB SCHIMMENTI: What we'll do over the long-term is work with the latest climate science, so that we're further protected, in the future.

NARRATOR: The electrical grid is just one piece of the vast infrastructure clobbered by Megastorm Sandy. On the West Side of Manhattan, the phone company Verizon also got a climate change wake up call.

CHRISTOPHER LEVENDOS (Verizon): The impact of Hurricane Sandy to Verizon was the largest impact to our wireline infrastructure in our 100-year history.

NARRATOR: Verizon world headquarters sits at 140 West Street, about 250 yards from the Hudson River, about five-and-a-half feet above sea level. The ornate art deco lobby is normally gilded and gleaming, but the night Sandy roared in, it was not such a pretty picture.

CHRIS LEVENDOS: We had the water come in through the front and the rear doors of the building. And then water gets into the elevator shafts, down the stairwells and begins to fill up the five sub-basements of this building.

NARRATOR: In the basement is the vault where Verizon keeps its Crown Jewels: telephone cables, most of them copper, the wires that connect their landline phone customers.

Bad enough, but below the vault is a pump system that delivers diesel fuel to the emergency generators on the 10th floor. But the pump was not waterproof. When it failed, the dominoes started falling: no pump, no power; no power and these crucial machines stop working—air compressors. Verizon pumps air into its copper cables to keep water from seeping in. Water, especially seawater, destroys copper.

CHRIS LEVENDOS: The network was completely destroyed, with one massive storm, in one very destructive night.

NARRATOR: The loss of that pump was a crucial failure in a night filled with catastrophic damage, due to relentless flooding.

By morning, the land-based phone lines in Lower Manhattan were almost totally wiped out, right in the financial capital of America. But there was, literally and figuratively, one glimmer of light amid the unimaginable mess. Fiber optic cables, long thin strands of glass that transmit voice and data with bursts of light, are far more efficient than copper wires, and best of all, they're impervious to water.

After Sandy, the company immediately started replacing its entire copper wire network in lower Manhattan with fiber. The changeover was supposed to take years; Verizon did it in six months.

In all, Sandy cost Verizon about one billion dollars.

And that crucial fuel pump? It's now in a watertight room with a submarine door.

Protecting New York's vulnerable and venerable subway system may be the biggest challenge of all. Sandy caused about five billion dollars' worth of harm to the nation's largest transit system. Hardest hit: South Ferry Station, at the southern tip of Manhattan. The station was only three years old, built at a cost of $550,000,000. The day after Sandy, it lay in ruins.

One of the culprits is believed to be this bundle of lumber two-by-eights. After becoming flotsam in the roiling seas, it tore through the makeshift barrier workers had erected at the station's entrance as Sandy approached.

JOE LEADER (Metropolitan Transit Authority): It was probably like a battering ram, when that wave, in fact, came, and the surges just, probably, just blew right through, and that was it. Where it came from, nobody knows. I don't want to say. I don't want to give Jersey a bad name, but it came from somewhere.

NARRATOR: More than 60 million gallons of seawater came rushing in filling the station almost to street level.

JOE LEADER: You try and prevent it, you try and deter it, and that's the best thing you could do. But can you really, actually stop it?

NARRATOR: It was not for lack of trying. As Sandy bore down on the city, transit workers frantically fought to stem the tide with inflatable dams, sandbags and plywood, but there was no stopping the water. Subway stations, rail yards and nine tunnels flooded.

MARC MENDE: Water was coming from everywhere. There was no way to stop it. You needed Superman, I guess.

NARRATOR: At the Hugh Carey Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, which normally carries cars and trucks between Brooklyn and lower Manhattan, there was little they could do.

MARC MENDE: We abandoned the place. We, basically, pulled everybody out of here.

NATS: Come on, we've got to go!

NARRATOR: Eighty-million gallons of seawater gushed in. The tunnel was practically full.

Work crews managed to clean it up. They removed the ceiling tiles and replaced enough lighting, cameras and communications gear to reopen the tunnel just two weeks after the storm. But there are years of work ahead to get things back to their pre-Sandy condition.

Ten months after Sandy hit, engineers tested a water-filled emergency dam that might offer a layer of defense for the tunnel the next time. They are also considering this idea, from West Virginia University: an inflatable plug.

In the meantime, carpenters have erected this plywood wall at the low point, where the water gushed in. But in the long run, will plywood and inflatables and other small-scale changes be enough to protect this metropolis?

JOE LEADER: If I made this airtight, and we did not allow the 66 million gallons of water that we pumped out to come into our system, where will that water be? It would be in the streets and would be in the basements and on the first floors of all the buildings surrounding. So, it's more than just us preventing the water to come out. It's got to be a really regional issue to decide, "How do you deal with something like that?"

NARRATOR: In the face of rising sea levels, how can an entire region be protected? With the threat growing every day, experts are looking for answers in a place all too familiar with the war against water: the Netherlands. The name itself says it all: "the low lands." Built on a swampy delta, much of the country lies below sea level.

TRACY METZ (Delta Commission): You really wonder why people settled here at all. This must have been such an uninhabitable, inhospitable place. It's a very soggy delta.

NARRATOR: That's what these are for. Windmills are essentially pumps.

PETER PAUL KLAPWYK (Miller): If the sails turn, the wheel will turn, this will start spinning.

NARRATOR: A giant Archimedean screw lifts the water out of the floodplain.

PETER PAUL KLAPWYK: In 1450, when they were introduced, this enabled us to live in areas where before, we couldn't live.

NARRATOR: And then, of course, there are the dikes, or levees, massive walls, usually made of earth, built to hold back floodwaters.

TRACY METZ: So, really, that's what the Dutch have been doing for a long time, is defending their country from the water. And defending also implies the feeling of the water as an enemy.

NARRATOR: In the winter of 1953, the enemy got the upper hand. A violent storm blew in from the North Sea. It was their Sandy and Katrina, combined.

TRACY METZ: In one night, over 1,800 people lost their lives; several hundred thousand lost their houses; about a million animals drowned.

JOS GELUK (Eastern Scheldt Barrier): My family knows what it is when your house is blown away by the water. And after that flood, we said, "Well, this may never happen again." And that was the reason for designing the Delta program.

NARRATOR: Jos Geluk is an engineer for the Delta program, or Delta Works, the massive flood protection system launched in the wake of the '53 flood.

In addition to a reinforced system of dams and dikes, locks and levees, the Dutch added what they hoped would be the ultimate weapons in water defense: enormous storm surge barriers across the mouths of rivers and estuaries.

Protecting Rotterdam harbor are two giant gates, together, bigger than the Empire State Building, designed to swing shut if the North Sea threatens; and bigger still, 50 miles southwest of Rotterdam, a five-and-a-half-mile-long storm surge barrier with 62 doors, ready to close at the push of a button.

JOS GELUK: We designed on a safety of a chance of flooding of once in 4,000 years.

NARRATOR: If New York City wants to stay dry in a world with rising seas, should structures like these be part of the plan?

JOS GELUK: I think more and more, the Americans become aware of the threat of the water. And they will spend money on protecting against the water.

JEROEN AERTS (VU University Amsterdam): As a Dutch man, you're quite surprised to see as a large city like New York, so many people exposed, and no levees. No protection at all was astonishing to me.

NARRATOR: Jeroen Aerts is a professor of risk and water management in Amsterdam. Like many of his colleagues here, he is a big believer in big structures to keep the water out. He thinks New Yorkers should think about walling themselves off from future megastorms.

JEREON AERTS: Don't rule out, yet, the barriers, because if sea level is going to rise very quickly, then you need a barrier.

NARRATOR: But with so many inlets for the sea to flow through, one barrier would never be enough to protect New York and New Jersey. The region would need to build an elaborate ring of strategically located barriers to fend off flooding from rising seas and worsening storms.

One scheme imagines a huge structure at the Verrazano Narrows, which separates Staten Island and Brooklyn. The concept is a hybrid of two Dutch designs: the giant barrier with the gates and the huge swinging doors.

Another idea is even more ambitious: a five mile long storm surge barrier that would span from Sandy Hook, New Jersey, to the Rockaway Peninsula, in New York.

Engineer Jonathan Goldstick would love to build it, though he admits "Fortress, New York" would cost tens of billions of dollars.

JONATHAN GOLDSTICK (CH2M Hill): The cost-benefit analysis is tricky, but it's a very good return, and it really keeps the water out.

NARRATOR: As sea levels continue rising, at some point in the future, even barriers like this won't be high enough.

JONATHAN GOLDSTICK: What the barrier should do is provide us with a relatively short-term option for protection, while we implement a plan that gets the city ready for future higher sea level rises.

If I were king of New York, I would build it.

NARRATOR: But if billions are spent on colossal barriers, will New Yorkers be left with a false sense of security? And might that delay action on the crucial question of how and where to build?

KLAUS JACOB: It looks like, "Wow! There's this incredible benefit," but essentially, we have delayed the problem.

NARRATOR: But even in the short term, giant barriers can cause huge problems. Just ask the Dutch.

TRACY METZ: There were a lot of unintended consequences. It's turned out that a lot of this intervention to keep the water out has had a detrimental effect on the country's ecology.

NARRATOR: Behind the permanent seawalls, they created stagnant lakes that are plagued by noxious algae blooms. The doors on the giant storm surge barrier were added to address that problem, but even with the doors open, the permanent barrier structures and manmade islands reduce the ebb and flow of the tides by 30 percent. Precious little sediment flows in. As a result, the estuary's sandbars, wetlands and oyster beds are disappearing, taking with them the natural flood protection they used to provide.

TRACY METZ: This is really one of the reasons that the Dutch are moving, now, towards a new approach to dealing with water and trying to intervene less.

NARRATOR: The reality is the quest to control big bodies of water almost always produces big problems. And nowhere is that more obvious than in the heart of America, on the mighty Mississippi. Since the 19th century, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has been on a mission to prevent flooding and keep the river in its place, with big reinforced levees and giant articulated concrete mats, laid along the banks to prevent erosion.

DENISE REED (The Water Institute of the Gulf): What we did in the 20th century was we really isolated the river from its delta plain. Then we decided that we really needed to, essentially, eliminate flooding from the Mississippi River, under most circumstances.

NARRATOR: Geomorphologist Denise Reed understands that rivers are meant to flood. That's why here, in bayou country, south of New Orleans, she lives in a house on stilts. One of Reed's biggest worries is that in our fight to stop flooding, we've essentially turned the river into a giant concrete pipe.

DENISE REED: The sediment that comes out at the end of the Mississippi, comes out of that long pipe that we've made, that essentially drops down into fairly deep water. That's not the way it used to work.

NARRATOR: The way it worked for thousands of years allowed sediment to spread out at the mouth of the river, creating the vast wetlands and swamps of the Mississippi Delta. But today, the delta is starved of sediment. As a result, every 40 minutes or so, an area of marsh the size of a football field vanishes.

DENISE REED: It's almost like a Swiss cheese effect. We've lost, I guess, since the 1930s, in an area the size of Delaware. That's a pretty large area.

NARRATOR: Those vanishing wetlands and marshes are nature's best defense against a storm, acting like giant speed bumps for waves surging in from the sea.

In the world of water control, they're known as soft defenses.

DENISE REED: So imagine the storm surge coming in. Instead of moving across a very smooth sandy bottom, it's moving across a rough surface. That really starts to take some of the energy out and slow down the storm surge.

NARRATOR: But by how much? To try and find an answer, the Corps of Engineers is using a complex model that runs on this supercomputer. Hydraulic engineer Jane McKee Smith has simulated a typical storm, without the benefit of the wetlands that exist today near New Orleans.

JANE McKEE SMITH (United States Army Corps of Engineers): You get larger storm surge and bigger waves hitting the area. And, certainly, if you look back the way they were hundreds of years ago, you would see a protective benefit from those wetlands. So, it's a very big issue.

DENISE REED: And if they continue to degrade, then clearly the city of New Orleans is not going to be protected the way we think it is now.

NARRATOR: New Orleans sits right in the midst of the Mississippi Delta. Today, the city is regaining its swagger, in part, thanks to this: 133 miles of new surge barriers, levees, floodwalls, gated structures and pumping stations that now ring the city.

The 14-and-a-half-billion dollar project, the epitome of hard defenses, was built by the Corps of Engineers in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

COLONEL RICHARD HANSEN (United States Army Corps of Engineers): We moved the perimeter outward. In some ways, we took the fight out to the storm surge instead of letting the storm surge come in to the city.

NARRATOR: In August of 2012, Hurricane Isaac gave the hard defense system its first big test. The storm brought 80-mile-an-hour winds and a surge that was only two feet lower than Katrina. This time the city did not flood.

But Denise Reed worries that if things don't change, this low-lying city will not be safe for long.

DENISE REED: If we have a city behind the levee and just open water on the other side, I don't think anybody thinks that is as good a condition as having a city and a levee, and extensive wetlands on the other side.

NARRATOR: To make matters worse, scientists say the city and the wetlands are sinking or subsiding. The state of Louisiana is fighting back, pumping millions of tons of sand onto barrier islands and decimated marshes. The goal: engineering a solution that replicates the way nature disperses that famous Mississippi mud.

So, can New York find a balance between hard barriers and soft defenses?

Landscape architect Kate Orff prefers the soft approach.

KATE ORFF (Columbia University): This is a typical blue mussel that we are looking to recruit on this rope.

NARRATOR: Orff says the blue mussels clinging to these ropes could be a lifeline for New York Harbor, and help the city survive a wetter future. The mussels are a keystone species, the first small step toward Orff's grand vision: a harbor filled with vibrant shellfish beds and small islands offering a natural defense against high water.

KATE ORFF: You can't just think about resiliency as closing the gates, putting up a giant seawall, but rather, through introducing reefs and offshore islands, ecological systems and marine life can play a role in making a more resilient harbor.

I think we have learned, over the past 100 years, that you cannot isolate these problems that we live in an ecosystem where everything is interconnected.

NARRATOR: Even though retired fire captain Dan Mundy spent a lot on hard defenses at his waterfront home, in Broad Channel, he's an evangelist for the gospel of soft measures, especially in the marshes of Jamaica Bay.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: As children, we used to drive our boats through these, so we knew these marsh islands like the back of our hand. We knew how big and how wide the creek was, we knew where the turns were and whatnot.

NARRATOR: Then, in the 1990s, he noticed that things were changing.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: The creeks got wider, the openings fell apart, instead of coming in and making a turn, it was a just big opening.

NARRATOR: Along with his son, also Dan, Mundy collected old maps and aerial photos of the marshes and compared them to new views.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: And when we looked at the interior of the marsh— we're looking overhead and looking down—we found out the whole interior was like a cancer. It was eaten out from inside out.

NARRATOR: The Mundys helped launch a scientific investigation. The findings were chilling: Jamaica Bay was losing 33 acres of marshland a year.

Eventually, scientists believed they found the culprit: polluted water was killing the sea grass.

DAN MUNDY, JR.: These plants that we see, the roots are like arteries, they go out feet.

NARRATOR: Without the web of sea grass roots knitting them together, the sandy islands dissolved away. Since then, the Mundys have spent years trying to save the marshes, with impressive results. Today, pollution is down; the water quality is up. They've helped raise millions of dollars to rebuild many of the islands, including this one. And they organize volunteer groups to plant new sea grass, to hold the sand together.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: And look at this. We have new growth coming up in this area. That's the most encouraging thing that I have seen since I started this project, because this means that they are going to be well established. We can let this go by itself now.

NARRATOR: The Mundys are stubbornly committed to this place, even though they live on the frontlines of the battle against sea-level rise.

DAN MUNDY, JR.: We're not moving. A little water ain't scaring us away. Do we retreat from the tornado alleys? Do we retreat from the mudslides? And do we retreat from the forest fires? No. So, if we apply that mentality across the board, there are really not many places we want to live.

NARRATOR: For them, natural defenses are a key weapon in the fight.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: We're going to get the water quality back to the way it used to be, going to rebuild these marshes that have disappeared, and that all is going to help with resiliency for the future; it's going to protect the shorelines.

NARRATOR: The Mundys found an unlikely ally in their quest to rebuild the marshes of Jamaica Bay: the Army Corps of Engineers, which built the new islands.

The Corps, now aware of the mistakes it made managing the Mississippi, seems to be going soft.

JOE VIETRI (United States Army Corps of Engineers): We have to think about the healthy estuary system, with salt marsh and soft, wave-absorbing-type features, like the islands and things of that sort. You can use a combination of gray and green infrastructure. Gray being our traditional concrete-type things and green being those softer solutions sets.

JANE McKEE SMITH: We know a lot about the hard structures, we're learning more about the natural features, but we really don't know a whole lot about how we combine these.

NARRATOR: For now, the Corps is focused on "brown," pumping sand, nourishing beaches in the Rockaways and on the Jersey shore. It is tried and true protection.

JOE VIETRI: We've only, basically, been looking at soft solution sets. Basically, right now, sand on a sandy beach, enough to buy us some time to take a deep breath and look at what those complex solutions might be.

NARRATOR: Most experts believe that, ultimately, soft measures alone won't be enough to stop a storm like Sandy from taking an enormous bite out of the Big Apple.

Less than a year after the megastorm hit, New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg released a 20-billion-dollar plan to make the city more resilient.

The plan calls for several small storm barriers at strategic locations, as well as plenty of new seawalls. And instead of a giant storm surge barrier, Bloomberg sees new developments, like this, as the best defense: "Arverne by the Sea," on the Rockaway Peninsula. Homes here were raised nine feet above grade, with a robust storm water drainage system. They sustained minimal damage during Sandy, a stark contrast to what happened nearby.

KATE ORFF: To me, that is the idea of resiliency—we can't keep the water out—if you can retrofit your building to be, be able to get wet, in a sense, but not be critically damaged during a storm event.

NARRATOR: This sea change in attitude, accepting that sometimes you have to let the water in, is exactly what's going on in the Netherlands.

TRACY METZ: The whole foundation on which the water safety system is built is really being subjected to a critical revision.

NARRATOR: The tide began turning in the mid-90s, after some devastating river flooding. At the same time, scientists were issuing increasingly dire warnings about climate change causing both sea level rise and more rain in the region.

HANS BROUWER (Room for the River): It meant that the expectation is higher river peaks, but also sea level rise. That would give a problem, because the rivers flow freely into the sea. So, when the sea level rises, it will be much more difficult to let the river water flow into the sea.

NARRATOR: The Dutch government launched a program called "Room for the River." At the most flood-prone locations in the country, they asked property owners to leave, buying them out, so the dikes could be moved inland. So when floodwaters come, they will flow onto empty land, without damaging homes or businesses.

HANS BROUWER: Now, we are talking about giving back lands to the river system. That was quite a step.

NARRATOR: It is not just farmland making the room. In the city of Nijmegen, they're reshaping the landscape to make some some space for the River Waal, bulldozing a peninsula, leaving just a small island.

After many centuries of performing a sort of alchemy, turning water into land, the Dutch are facing the limits of their sorcery. Not everyone, everywhere, can be kept safe from the water. Is this the beginning of a tactical retreat?

TRACY METZ: The Dutch don't see this as a retreat. They see it as a form of accommodation. Now we're moving towards an approach in which water is seen as, perhaps not a friend, but a frienemy, somewhere in between.

NARRATOR: In Rotterdam, where parts of the city lie 22 feet below sea level, the Dutch are going even further, coming up with innovative places to put floodwaters.

DANIEL GOEDBLOED (Municipality of Rotterdam): We don't have room in the city of Rotterdam to just add more canals, so we have to think of other things. And that's one of the things we're doing, here, is we're storing it, actually, underground.

NARRATOR: When a museum built this underground parking garage, the city added on a two-and- a-half-million-gallon holding tank. About 10 times a year, heavy rains prompt them to open the valves and fill the tank. It prevents flooding and stops untreated sewage from flowing into the harbor.

The city is also creating public plazas that are walled and tiered, so they can double as retention ponds.

DANIEL GOEDBLOED: When it starts to rain, this fills up, and all these terraces fill up, and kids just love it. They put on their boots and they just run through it.

NARRATOR: Another, more elaborate one is under construction near a high school. When it rains here, the playing field will fill up and hold water until the pumps and sewers can handle it.

Keeping their feet dry has always been a Dutch priority, but the key lesson they've learned over the years? Simply fending off the water, as if it were a mortal enemy, is like tilting at windmills.

Whatever New York does, its defenses could be challenged sooner than expected, because, not only is sea level rising, but future storms could be more destructive.

When Megastorm Sandy hit the Northeast, many asked whether this monster was the product of climate change.

J. MARSHALL SHEPHARD (University of Georgia): It's not clear to me that this storm was caused by climate change, but I think that we are in an era where climate change is likely increasing the risk or probability of certain types of extreme weather events.

NARRATOR: Climate models suggest that, overall, the number of hurricanes might go down, but the ones that do form could be even more powerful than they are today.

KERRY EMANUEL (Massachusetts Institute of Technology): What all the models and theories seem to agree on, at least, globally, at this point, is that the frequency of the very high intensity, Category 3, 4 or 5 events should go up.

NARRATOR: Hurricanes are giant heat engines, fueled by evaporation from the warm surface of the ocean. Once a hurricane gets revved up, a warmer climate means more evaporation and a stronger storm.

KERRY EMANUEL: If you look at the most powerful hurricanes on the planet, they have winds near the surface of about 200 miles per hour. It's conceivable that a hundred years from now, the top-ranking hurricanes will have wind speeds of say 220 miles per hour, about a 10 percent increase.

NARRATOR: That may not sound like very much, but as wind speed increases, the potential for damage rises exponentially.

KERRY EMANUEL: So, you're talking about something that's half again more damaging than current hurricanes. That's what we worry about.

NARRATOR: Bigger storms, higher seas—is a retreat from the water inevitable?

KLAUS JACOB: In many places, it will be absolutely inevitable. Florida is doomed, not today, not next year, not next decade, but 200 years from now, there will be one big swimming pool.

NARRATOR: So does it make sense to invest in expensive projects like beach renourishment, year after year, to protect a way of life that may not be sustainable?

JOE VIETRI: It makes a lot of sense to put sand on the beach in the Rockaways, right now, but I would not suggest to you that 30 years from now, or 35 years from now, that that might still make a lot of sense.

NARRATOR: And does it make sense for federal taxpayers to subsidize flood insurance, an incentive for people to build and rebuild right on the water's edge, in low-lying parts of New Jersey, where 30,000 businesses and homes were damaged or destroyed by Sandy; or in Broad Channel? Premiums here have skyrocketed. Dan Mundy worries it could be a mortal blow to his community.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: These are workers that you're talking about. These are people who get on the A-train; they go to work every day; they make $80,000, they make $90,000 or something like that a year. They can just about afford to pay their mortgage and whatnot, and you bring these increases in on them. That's going to be a problem.

NARRATOR: Not an easy problem to solve. And it's just one of many dilemmas in the wake of Megastorm Sandy.

DAN MUNDY, SR.: When we got our back to the wall, America can respond. And this thing was so big, and it's going to affect so much, and it's going to affect so much of the economy of the United States that this is the game changer, right here.

DENISE REED: We have an opportunity, after these big events, to really think broadly. We shouldn't waste those opportunities, because there is an event bigger than Sandy out there, I'm sure.

Broadcast Credits

- WRITTEN, PRODUCED, AND DIRECTED BY

- Miles O'Brien

- EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Julia Cort

- ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

- Will Toubman

- EDITED BY

- Brian Truglio

- ADDITIONAL EDITORS

- Michael H. Amundson

Daniel McCabe

Jean Dunoyer - CAMERA

- Cameron Hickey

Miles O'Brien - ADDITIONAL PRODUCERS

- Kate Tobin

Suzi Tobias

Cameron Hickey - FIXER

- Bas van der Ree

- ANIMATION

- G.R.O.W./ Lead Animator Aaron Nee

- ASSISTANT EDITOR

- Michelle Mizner

- NARRATED BY

- Craig Sechler

- MUSIC

- ScoreKeepers Music

- ONLINE EDITOR

- Jim Ferguson

- COLORIST

- Jim Ferguson

- AUDIO MIX

- John Jenkins

- ARCHIVAL

- Associated Press

Jon Bowermaster/ Footage Search

Dragonfly Film and Television Productions Ltd

DVIDS

City of New York - Footage by Framepool

- Getty Images

Hugo Janse

Mangrove Media, LLC/ Jen Schneider

John Mattiuzzi

Scott McPartland

NASA/ Goddard Space Flight Center

NASA/NOAA GOES Project

National Science Foundation

Casey Neistat

NOAA

Pond 5 - Ekaterina Pugacheva

- T3Media

The Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment of Netherlands

The Rijkswaterstaat

TwisterChasers/ Jeff Piotrowski

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ERDC

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Vicksburg

USGS/ National Wetlands Research Center

West Virginia University

Wim Robberechts & Co - SPECIAL THANKS

- Jason Amundson

Tomasz Crerwinski

Jean Paul de Garde

Mike DiPalo

Mark Fahnestock

Shatisha Haywood

HEIST

Michal Jaszewski

Alexandro Kioichenko

Kiva Kuan Liu

National Science Foundation

Kathy and Phil Riley

Jeremy Sciarappa

Sims Municipal Recycling - Pieter Smit

- Matthew Troy

Martin Truffer

Richard R. York - NOVA SERIES GRAPHICS yU + co.

- NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Walter Werzowa

John Luker

Musikvergnuegen, Inc. - ADDITIONAL NOVA THEME MUSIC

- Ray Loring

Rob Morsberger - POST PRODUCTION ONLINE EDITORS

- Jim Ferguson

Spencer Gentry - CLOSED CAPTIONING

- The Caption Center

- PUBLICITY

- Eileen Campion

Victoria Louie - SENIOR RESEARCHER

- Kate Becker

- NOVA ADMINISTRATOR

- Kristen Sommerhalter

- PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

- Linda Callahan

- PARALEGAL

- Sarah Erlandson

- TALENT RELATIONS

- Scott Kardel, Esq.

Janice Flood - LEGAL COUNSEL

- Susan Rosen

- DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION

- Rachel Connolly

- DIGITAL MANAGING PRODUCER

- Kristine Allington

- SENIOR DIGITAL EDITOR

- Tim De Chant

- DIRECTOR OF NEW MEDIA

- Lauren Aguirre

- DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATE

- Lisa Leombruni

- UNIT MANAGER

- Ariam McCrary

- PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Stephanie Mills

- POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

- Brittany Flynn

- POST PRODUCTION EDITOR

- Rebecca Nieto

- POST PRODUCTION MANAGER

- Nathan Gunner

- COMPLIANCE MANAGER

- Linzy Emery

- BUSINESS MANAGER

- Elizabeth Benjes

- DEVELOPMENT PRODUCER

- David Condon

- PROJECT DIRECTOR

- Pamela Rosenstein

- COORDINATING PRODUCER

- Laurie Cahalane

- SENIOR SCIENCE EDITOR

- Evan Hadingham

- SENIOR PRODUCER

- Chris Schmidt

- SENIOR SERIES PRODUCER

- Melanie Wallace

- MANAGING DIRECTOR

- Alan Ritsko

- SENIOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

- Paula S. Apsell

A NOVA Production by Miles O'Brien Productions, LLC, for WGBH Boston

© 2013 WGBH Educational Foundation

All rights reserved

This program was produced by WGBH, which is solely responsible for its content.

IMAGE:

- Image credit: (House damaged by Hurricane Sandy)

- Courtesy: FEMA/Patsy Lynch

Participants

- Jeroen Aerts

- VU University Amsterdam

- Michael Bloomberg

- Mayor, New York City, 2002-2012

- Hans Brouwer

- Room for the River

- Kerry Emanuel

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Stephen Flynn

- Northeastern University

- Jos Geluk

- Eastern Scheldt Barrier

- Daniel Goedbloed

- Municipality of Rotterdam

- Jonathan Goldstick

- CH2M Hill

- Col. Richard Hansen

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- David Holland

- New York University

- Klaus Jacob

- Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

- Peter Paul Klapwyk

- Miller

- Joe Leader

- MTA

- Christopher Levendos

- Verizon

- Jane McKee Smith

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- Marc Mende

- MTA

- Tracy Metz

- Delta Commission

- Daniel Mundy

- Broad Channel, NY

- Kate Orff

- Columbia University

- Denise Reed

- The Water Institute of the Gulf

- Robert Schimmenti

- Con Edison

- Marshall Shepherd

- University of Georgia

- Joseph Vietri

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Preview | 00:30

Full Program

Full program available for streaming through

Watch Online

Full program available

Soon