John Smith's Bold EndeavorIn Disney's recent version of the Pocahontas story, as in countless iterations before it, John Smith appears as a dashing romantic hero, smitten by the Indian "princess." Their relationship symbolizes the bridging of two cultures, and more particularly, shows how Indians could enlighten Europeans to the wisdom of the natural world. It's a fantasy that appeals to Americans today in part, perhaps, because it obscures an ugly truth: the relationship between Smith and Pocahontas, and more broadly between the Jamestown colonists and Pocahontas's people, was one of betrayal and dashed hopes, as this interview with historian David Silverman of George Washington University makes clear. Great expectationsQ: Why did John Smith and his English compatriots journey to Chesapeake Bay in 1607?

David Silverman: The first Jamestown colonists were fundamentally part of a business venture, a venture designed to produce wealth for its investors. What form that wealth would take they weren't sure. The Spanish example in South America and Central America taught the English that around the next corner, in the American interior, might be a great Indian empire rich in gold and silver. But the colonists also had more modest goals: perhaps they might find iron or copper, or they could grow crops like citrus fruits. They also wanted to find a waterway that would give them an easy passage to Asia and all of its riches in the form of porcelain, silks, and spices. Q: When the colonists first landed, what was foremost on their minds, finding riches or finding a way to sustain themselves? Silverman: The main directive they had was to find wealth. Now, how to do that while also sustaining the colony was the great question. They expected to raise some amount of food, but they didn't expect this colony to be entirely self-sufficient, not in its first years. The Spanish model and the English example of Roanoke in the 1580s, even though that colony failed, taught that Europeans might depend upon native people for sustenance. And indeed, that's the strategy they intended to follow. Q: How much did they know about the Powhatan people before they arrived?

Silverman: Europeans had been exploring the North American Atlantic coast for the better part of a century before the founding of Jamestown. So the English had information about native people on the coast: about how their polities were organized, about their economies, about what they would trade for European goods. What they didn't know was what Indians were like in the interior. Was there [something like] an Inca kingdom in the interior? They desperately wanted to know that. Q: What were the Indians' preconceptions about the English? Silverman: The Indians knew two big things through their previous experience with Europeans. The first was, these people were potentially very dangerous, very treacherous. They were armed to the teeth. They could turn on native people in the blink of an eye and for reasons that the natives couldn't fathom. But secondly, these English possessed goods that the natives craved. Now, some of these goods were things that we might consider bobbles and beads, worthless trinkets, ribbons, and the like. But there were other items, too, that could vastly improve their quality of life: metal cutting tools, axes and swords, awls and scissors, metal needles (which were a radical improvement over the bone needles or stone needles that native peoples used), brightly colored cloth, metal kettles that native women could place directly over the fire—quite unlike their own clay or wooden pots. And so even though they knew the English were dangerous, the Indians were drawn to them.

A wayward son[Editor's Note: The Indian people the Jamestown colonists encountered were known by the same name as their chief, Powhatan.] Q: According to John Smith's account of the famous event—when Pocahontas allegedly rescued him from execution—her father, Powhatan, let Smith live but also expected something in exchange. What was it? Silverman: John Smith thought, and I believe he was right, that Powhatan spared his life because Smith was more valuable to him alive than dead. Powhatan wanted Smith to broker trade relations between the English and the Powhatan people. Q: And was Pocahontas a part of this decision? Silverman: If John Smith's account, written in the 1620s, can be believed, Pocahontas was at the center of her father's decision to spare his life and then to set him up as a cultural broker, as a trade broker between the Indian and English communities. Q: Several historians now see what took place between Powhatan and Smith in terms of an adoption. What would Powhatan's perception of this adoption have been? Silverman: We know that Powhatan called Smith "son" after freeing him from captivity at Werowocomoco. Well, what would a son's responsibilities have been to his father? First and foremost, to provide reciprocal hospitality, meaning that Indian visitors to Jamestown, just like English visitors to the Indian communities, would receive food, lodging, and good treatment. It meant that these visitors would leave their weapons outside the village boundaries. The Indians would say that kin don't need to guard one another against kin.

Secondly, family members provide for one another's needs. How do you do that? Through trade would have been the Indian answer. The Indians would provide the English with food and military protection, and the English would provide the Indians with what they needed: copper, bells, beads, cloth. And over and over and over again, the Indians asked for weapons. Q: How did Smith fare as a son? Silverman: Initially, Smith fulfilled Powhatan's expectations in terms of brokering trade. But he fell short of Powhatan's expectations as a son in several respects. First, Powhatan essentially ordered Smith to move Jamestown to a new site within Powhatan's dominions, where the English could be kept under closer watch. Smith refused to do this. Powhatan also expected Smith's community to be subordinate to his, to be subject to his rule, and probably to pay him tribute. They did not. Smith was willing to set up a relationship of rough equality while Jamestown got its footing, but Smith's plan was for the English to seize the superior position as soon as they could.

And thirdly—and I'm basing this opinion on inference, on what we know about other native peoples—Powhatan might have expected intermarriage. Marriage between the groups, and the production of mixed children, would give them a mutual interest in keeping the peace and ensuring prosperity. If the Powhatan Indians did indeed expect large-scale intermarriage between peoples or even just between the elites of both communities, they were sorely disappointed. The unanswerable questionQ: What happens to John Smith after he is released and returns to Jamestown? Silverman: John Smith returns from his captivity in Werowocomoco. He has a large native escort. He has set up relations between Jamestown and the Powhatan chief. He has set up the basis for trade relations. These are remarkable accomplishments. So what does he receive for his efforts? He's clapped in jail. Why? For his mismanagement of the venture that got him captured in the first place. Moreover, the leaders of Jamestown suspect he is trying to set himself up as the supreme leader through his alliance with the Powhatans. Q: So he came back with a threatening power?

Silverman: The English leadership deeply feared that John Smith would try to set himself up as the dictator of Jamestown by manipulating Indian military strength. Q: But after a short time, Smith's let out. And then comes what has been described as a "golden interlude" of peace. Is that right? Silverman: The period of several months after Smith's return to Jamestown has often been called a golden age in English-Indian relations. I think the term is vastly overstated, but there was a steady if uneasy peace. Trade was taking place during this time. Indians were coming and going from Jamestown on a fairly routine basis. And one of those Indian visitors was Pocahontas herself. She would show up at Jamestown, sometimes as part of official Indian delegations, sometimes just to visit, perhaps to visit John Smith. Q: So here's the inevitable question: What was the nature of their relationship? Silverman: Well, we do know that there was a relationship between John Smith and Pocahontas. We know that she was present at Jamestown at least several times in the months after John Smith's return from Powhatan captivity. She shows up in a Powhatan word list, a list of phrases that Smith compiled. But what was the nature of their relationship? Was it romantic? Unlikely, but we can't be sure. Some colonists suspected that it might be romantic. Was it political? Absolutely. We know that John Smith wanted to take the lead in English relations with the Indians, and Pocahontas was one of his allies, it would appear, in that effort. Did Pocahontas view John Smith as a relative? Perhaps. Her father called John Smith "son," and so the implication is that he was like her brother. We also know that Pocahontas was a special kind of person. She did not abide by the normal rules set up for a teenage Indian girl during this period. Here she is, in a potentially hostile environment, in a fort of foreigners populated almost exclusively by men in their late teens and early twenties, armed to the teeth, with a history of engaging in hostilities with native people. Yet there she is, with or maybe even without her father's permission and knowledge. We know that she accompanied and perhaps even headed up Indian delegations to the English to bring them food and eventually to free Indian captives being held at Jamestown fort. And she was her father's favorite. She was a special person: bold, vivacious, obviously very, very smart, and savvy in intercultural relations. The war beginsQ: Why did the Indians stop trading food to the English? Silverman: There are two points of stress. First, the English had traded so much copper to the Indians that the Indians were now unwilling to trade plentiful amounts of food for small bits of copper, like they once did. The second point of stress was that the English arrived in Virginia in the midst of a serious, serious drought unlike any that had been seen by generations of Indians. The Indians simply didn't have enough of a surplus of corn, beans, and squash to trade to the English and feed themselves at the same time.

Now, the Indians were willing to trade their corn for one item: over and over and over again they demanded weapons—swords and firearms—something John Smith in particular and the English generally were unwilling to provide. Q: What is Smith's response to the food supply drying up? Silverman: Smith's primary response is to seize that food, to force the natives to trade at gunpoint, and if the natives won't trade, to attack native villages and simply take what he and the English want. So we find armed English military expeditions to native communities, which are resulting in bloodshed and the rather ironic development of the English burning down cornfields after they've taken all the food they can carry away. Q: Were they burning down the villages too? Silverman: Sometimes. What we have, in essence, are the beginning stages of a war. Q: But in the midst of this warfare, Smith records that Pocahontas actually acts to save his life, is that right? Silverman: Yes. Among the strong-armed efforts to force the Indians to trade food was an English expedition to Werowocomoco. The Indians, as usual, insisted the English leave their weapons at the edge of the village, which the English were unwilling to do. In the midst of negotiations, all of a sudden Chief Powhatan disappeared. The English were fairly certain they were about to come under attack. And indeed, Pocahontas herself, according to John Smith, came and gave him a warning that he and his men were in peril. And so the English beat a hasty retreat. Q: But why would she do that? Silverman: We simply can't know Pocahontas's intent. Now, it might very well be that she empathized with the English, that she had feelings toward Smith and didn't want to see him die. It also might be that this was an act of political theater in which Powhatan sent Pocahontas to give what amounted to a warning to the English, to say, "If I wanted to cut you off I could. Reform your behavior. Act the way I expect you to act." Such warnings are consistent with Indian ways of diplomacy and war. We have contradictory signals; we can't sort them out through the meager historical record. A devastating "accident"Q: Then what horrible thing happens to Smith? Silverman: Well, essentially a keg of gunpowder lying between his legs explodes. Q: Talk about excruciating pain. Silverman: Yes, excruciating pain, absolutely. Q: And was it an accident? Silverman: Contemporaries said that this explosion was an accident, and yet there are conspicuous hints that suggest it was deliberate, that someone within the English community was trying to kill or to hurt Smith and remove him from power. We do know that the rivalry between John Smith and other English elites at Jamestown was at an absolute pitch during this time. Smith, always bold, was being even more aggressive at trying to dictate English-Indian policy. And suddenly, this explosion occurs, and Smith's forced to return home. Q: So it's safe to say that some people were happy to see him go. Silverman: More than a few Englishmen were happy to see John Smith go. They didn't like his overbearing manner, his rising above his class station in life. Now he was gone, and yet the Indians and the English needed him to serve as an ambassador between their communities more than ever. Q: What is Pocahontas told? Silverman: Pocahontas is not told that John Smith is injured and is going back to England to recover; she is told that Smith is dead. Q: What then happens to the colonists? Silverman: The English enter a severe period of starvation in which they lose most of their numbers. Almost everyone at Jamestown is sick. They're malnourished. They're coming down with a variety of diseases, including dysentery and salt poisoning. And they're psychologically depressed. They're under intermittent siege by native people whom they deeply, deeply fear. They feel isolated. They feel at risk. And they turn inward, almost collapsing upon themselves, and they refuse to do the basic functions that people need to perform in order to survive. Q: But the colony does survive. Some years pass. Pocahontas is captured. Can you jump us ahead to that point? Silverman: In April of 1613, the English capture Pocahontas and hold her as a bargaining chip in their diplomacy with Powhatan, offering to return her in exchange for peace. Over and over again the Powhatan chief rebuffs them. He might have been thinking that Pocahontas could learn their ways, learn their language, cultivate their leaders, and try to broker a truce between the peoples. If that was his strategy, it was a very, very savvy one, because that's exactly how things played out. During her captivity at Jamestown, Pocahontas falls in love with an English settler, John Rolfe. Was this coincidence or was it strategy? It's hard to know. What we do know is that the marriage between Pocahontas and John Rolfe is a key step in establishing an uneasy truce between the Powhatan and English peoples in early Virginia. A legacy of betrayalQ: A few years later, Pocahontas travels with Rolfe to England. What does she find out about John Smith? Silverman: Among the shocks that Pocahontas receives while visiting England in 1616 is that John Smith, whom she had been told was dead, is indeed alive and well. It crushed her to learn this news. It crushed her not only that the English had been lying to her all along but that John Smith, a man with whom she had a personal relationship of some sort or another, had done absolutely nothing to contact her, to contact her people, to contact her father, who called Smith his son. Q: Can you imagine how she would have felt when she finally met Smith? Silverman: However Pocahontas was feeling when she finally saw John Smith—whatever heartache she was feeling, whatever fury she was feeling—she behaved with dignity. She reminds him that her father called Smith "son." And the implication is, "We were supposed to be like family. We were responsible for one another." The implication is, "Do you know what has been happening back in Virginia to my people by your people since you left?" The implication is that Smith could have made a difference and did not. Q: Why is the story of Smith and Pocahontas of profound importance to us, to American history? Silverman: The Pocahontas story, the Pocahontas myth, has traditionally been told to make Americans feel better about the evils of colonization. Pocahontas seemed to acquiesce to English colonization, to willingly adopt Christianity and "civility." But I think the larger lesson of Pocahontas's life and her experience with Smith and the English is that there was a potential in the early relationships between Indians and colonists to set up something mutual. To set up, as the Indians would have it, a relationship of kin in which the two peoples help to meet each other's needs and live as a single people. Those expectations were sorely dashed. They were sorely

dashed in the mind of Pocahontas, sorely dashed for the Powhatans, and sorely

dashed for Indian peoples across the continent over the course of three

centuries of colonization by European powers in the United States. That's

the basic lesson of the Pocahontas story and the story of early Jamestown.

|

This engraving appeared in Smith's Generall Historie, a self-promoting account of his adventures in America in which he publicized the story of his rescue by Pocahontas, roughly 17 years after it supposedly took place.

For "Pocahontas Revealed," NOVA tracked down trade goods such as metal kettles that might have been exchanged between Jamestown settlers and Powhatan Indians.

The English settlers refused to barter the one type of good the Powhatans craved most—weapons—because they feared that muskets and metal swords would eventually be turned against Jamestown.

As more and more copper became available to the Powhatans, its exchange value dropped. Smith tried in vain to control the flow of copper, but sailors on English supply ships undermined his efforts.

The 1907 World's Fair held in Norfolk, Virginia celebrated the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown. Like many depictions, this logo shows a harmonious relationship between Smith, representing Europe, and native Americans. Such harmony, if it ever existed, was short-lived.

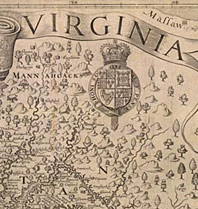

This map, based on Smith's exploration and description of the region and first published in 1612, is the work of a culture intent on conquering a "virgin" land.

David Silverman is an Associate Professor in the Department of History at George Washington University, where he teaches Early American and American Indian history. |

|

Interview conducted in December 2006 by Lisa Q. Wolfinger, one of the producers of "Pocahontas Revealed," and edited by Susan K. Lewis, editor of NOVA online Pocahontas Revealed Home | Send Feedback | Image Credits | Support NOVA |

© | Created April 2007 |