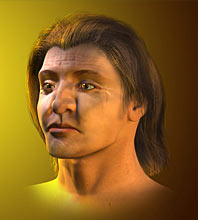

The Science of JamestownFor centuries, scholars interested in Jamestown and Werowocomoco, the Indian village where Pocahontas lived, could rely only on contemporary accounts and later historical works. But recent archeological excavations and other scientific research conducted in what experts believe to be the sites of these two settlements in eastern Virginia have revealed tantalizing new evidence. Still being analyzed, the evidence is helping to further flesh out the story of these sites and their most famous residents, John Smith and Pocahontas. In this time line, explore some of the more significant scientific findings, set against the backdrop of historical record.—Rima Chaddha December 1606–May 14, 1607Captain Christopher Newport leads three ships carrying 105 male settlers across the Atlantic. In May, they establish Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America. May 26Paspahegh Indians, in whose territory Jamestown is built, launch an attack on the settlers. A boy dies after being struck in the leg by an arrow. Recent excavations at the original Jamestown settlement seem to confirm many settlers' recorded deaths, including the boy's: archeologists discovered a grave with a young male's skeleton and an arrowhead near his leg, which was probably still in the boy's flesh when he died. At right, researchers have used facial reconstruction software on a skull to show what another colonist might have looked like. The skull is thought to have belonged to Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, a founding father who was a primary force behind the expedition to Jamestown. JuneFollowing the attack, the colonists decide to build a protective wall around their settlement, which they complete on June 15 and name James Fort. A week later, Captain Newport sails back to England, while a preselected council stays behind to run the town. Historians had long thought that the site of James Fort had eroded over time into the James River, but excavations beginning in the mid-1990s revealed dark pockets of soil in the area where the fort had once stood. These pockets contained organic material, the remains of wooden posts that had long since rotted away. To the archeologists who made the discovery, these postholes confirm that only a corner of the south wall, the wall closest to the water, eroded away. SeptemberThe colony falls into decline at the hands of the dysfunctional council, while relations with Indians, upon whom the colonists rely for food, sour further. By September 10, 46 Englishmen are dead, and the council executes one of its own for causing discord. Two days later, the council deposes its president. Mid-DecemberCaptain John Smith leads an expedition in search of Indians willing to provide the colonists with food, but a group of Powhatan Indians ambushes the team, kills some of the members, and takes Smith prisoner. The Powhatan chiefdom includes about 15,000 people in 30 districts, counting that of the Paspahegh. A map from this era marks Werowocomoco with what looks like a "D" within another "D." This symbol could represent the two parallel ditches (seen here, filled in) found in excavations at Purton Bay in Gloucester County, Virginia, where archeologists believe Werowocomoco once stood. The ditches appear to surround Werowocomoco's eastern half, dividing the village into what experts believe is a religious or restricted area where the chief (also called Powhatan) and other high-status chiefdom members probably spent their time, and a secular area to the west. Circular stains of soil containing organic matter hint at the eastern half's importance: scholars believe that the stains mark the outline of the largest longhouse yet found in Virginia, possibly belonging to Chief Powhatan himself. (The wooden longhouse is believed to have rotted away like James Fort.) Additionally, pottery and other artifacts found to the east are better made than the cruder fragments to the west. December 29After about two weeks in captivity, Smith is brought before Chief Powhatan. According to Smith's later accounts, Powhatan calls for his execution but changes his mind after his daughter Matoaka, best known by her nickname, Pocahontas, pleads for the stranger's life. We will likely never know whether Pocahontas actually saved John Smith's life or was simply playing her appointed role in an Algonquian adoption ritual, in which Smith's reprieve represented his rebirth into the chiefdom. But archeological evidence does suggest that the adventurer might have spent time at Werowocomoco. Among tempered pottery fragments, arrowheads with fine projectile points, and other artifacts that place Powhatan Indians at Werowocomoco during the early 1600s, excavators found pieces of copper chemically identical to English copper uncovered at Jamestown. Experts think it likely that Smith carried the metal scraps seen here in hopes of establishing a trade agreement for food. Local Indians valued copper for its luster. January 1, 1608Smith is released shortly after his reprieve and returns to Jamestown, where he finds just 38 of the original 105 colonists alive. Hungry and weak, some of the survivors prepare to depart for England on the tiny Discovery, one of the ships that had brought them from England. But Smith, in an attempt to keep the colony afloat, aims one of the fort's cannons at the ship to prevent them from leaving. January 2In one of North America's first trials by jury, Smith is condemned to hang for the deaths of his fellow adventurers during the December ambush and, by some accounts, even has the noose around his neck just as Captain Newport returns to Jamestown with fresh supplies and 60 new settlers. Newport puts a stop to Smith's execution and soon sails off to London a second time. January 7A week after Smith's release from Werowocomoco, a fire engulfs James Fort, destroying settlers' homes and clothing. At Smith's request, his newly adopted Powhatan family helps the colonists survive the harsh winter. January–summerAs relations between the Indians and the English improve, Pocahontas (who by some accounts is not yet in her teens) serves as an emissary for her father. She negotiates with Smith for the release of some of her people captured in an earlier raid on Jamestown. English narratives state that Pocahontas and other Indian women spent a fair amount of time at Jamestown, and archeological evidence seems to support this. Many fragments of early 17th-century Indian pottery (including the pieces reassembled here) have been recovered from Jamestown and indicate that Indian women might have cooked or even lived there. September–OctoberAnother supply ship reaches the Virginia colony, bringing more settlers to Jamestown and increasing the overall population to about 600. In October, Smith and a few of his men crown a reluctant Chief Powhatan as a vassal of King James I. Fall–winterAs winter approaches, the Indians stop sharing their food supplies with the colonists. Violence erupts on both sides. Analyses of tree rings (like those seen in this image) that were performed on cores drilled from centuries-old trees show that Virginia was in the midst of a seven-year drought when the Indians stopped feeding the colonists. Tree rings from this era are narrow, indicating little growth. Scholars believe that the Indians simply lacked enough food to share with the colonists. Early 1609Conditions also worsen for the Indians, and escalating violence forces Powhatan and his people to abandon Werowocomoco. July 24A hurricane sinks one Jamestown-bound supply ship and maroons another in Bermuda. SeptemberJohn Smith sustains serious injuries in a gunpowder explosion and returns to England to recover. Powhatan is told that Smith is dead, and Smith essentially turns his back on the Powhatan people, making no attempt to contact them. He never returns to Virginia. September–May 1610This marks the beginning of the "starving time," which devastates the Jamestown population. Of the 600 citizens the colony boasted in fall 1608, just 60 remain by May 1610. June 4, 1613Captain Samuel Argall captures Pocahontas and brings her to Jamestown, where she is held hostage in an attempt to gain leverage over her father. April 5, 1614After 10 months in captivity, Pocahontas converts to Christianity and takes the name Rebecca. She marries colonist John Rolfe on April 5. January 1615Rebecca bears a son, Thomas, whose birth makes the Rolfes one of the acclaimed First Families of Virginia. 1616John Smith learns that the Rolfes will be traveling to England. Perhaps out of guilt for having abandoned Pocahontas and the Powhatan, he writes a letter to England's Queen Anne, planting the seeds of a legend. He recalls: "…[A]t the minute of my execution, [Pocahontas] hazarded the beating out of her own brains to save mine; and not only that, but so prevailed with her father, that I was safely conducted to Jamestown." June 3The Rolfes arrive in England, where Pocahontas and Smith meet again. According to Smith's accounts, Pocahontas at first does not take kindly to him, but eventually talks to him, reproaching him for his abandoning the Powhatan people. March 1617Pocahontas falls ill, probably with pneumonia or tuberculosis, and dies. She is buried in Gravesend, England. According to Rolfe, her last words to him are, "All must die. ‘Tis enough that the child liveth." 1618Powhatan dies. In coming years, relations between the Indians and the colonists will continue to waver, alternately improving and declining through time. 1624Smith publishes his Generall Historie, in which he gives a more detailed description of his capture and alleged reprieve at Werowocomoco. 1631John Smith dies in England, having never returned to Jamestown, where archeologists are still working to uncover more of the colony's story. To

learn more about Pocahontas, see Images of a Legend. For more on John Smith,

see John Smith's Bold Endeavor.

|

|

|

Pocahontas Revealed Home | Send Feedback | Image Credits | Support NOVA |

© | Created April 2007 |