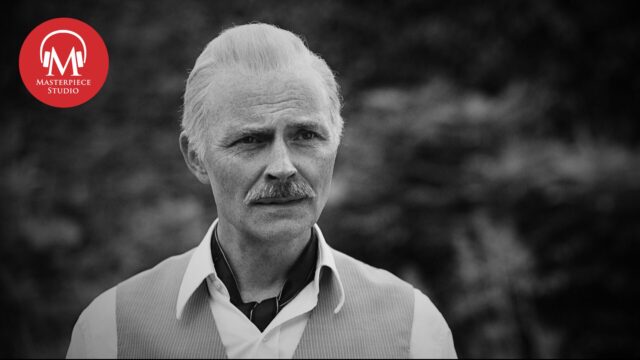

A World War II documentary helped spur Peter Bowker to create his multi-layered, international drama, World On Fire. With a season of the series dedicated to every year of the global war, the creator offers new insight into his first year, and subtle previews of the season still on the horizon.

Download and subscribe on: iTunes | Spotify| RadioPublic

Transcript

Jace Lacob: I’m Jace Lacob, and you’re listening to MASTERPIECE Studio.

It probably feels like you’ve already consumed enough World War II history in pop culture, from movies to novels to even other MASTERPIECE series themselves…but, screenwriter Peter Bowker knows there’s room for at least one more series about World War II — and it’s one like you’ve never seen before.

CLIP

Mrs. Rossler After what happened in the cinema, I will teach Hilda at home for now.

Nancy You are just going to hide her away because of her epilepsy?

Mr. Rossler What you saw. Her fit. Please. Tell no one. Tell no one.

Nancy Of course not. Come on, Claudia. You must know I can keep a secret. We’re drinking buddies!

Mr. Rossler This is serious, Frau Campbell. Very serious.

Jace World on Fire is a tale about a different side to the epic World War — an ordinary, human side in less visited parts of the story. A Polish waitress in Warsaw. A British jazz singer in Manchester. An American journalist in Berlin, and her nephew, a gay doctor in Paris.

CLIP

Albert I’m sorry, Eddie.

Eddie Colored and queer with Nazis in charge? Good luck with those chances.

Jace Bowker plans to devote a full season of his series to every year of the war, and with the second season already confirmed, he was eager to speak with us about the story still to come, both in this fiery first season, and the seasons beyond.

Jace And this week, we are joined by World on Fire creator, Peter Bowker. Welcome.

Peter Bowker Nice to be here. Thank you.

Jace Where did the initial idea for World on Fire come from, and how important to the concept was the notion of ordinary people enduring the extraordinary circumstances of the Second World War?

Peter The original idea came about because both Damien Timmer, the executive producer, and I are obsessed with a 1970s-documentary series called World At War, which told the story of World War II from multiple perspectives, including Germans and so on. And the recent Vietnam War documentary is very similar in its scope and tone, and Damien said, ‘Would I ever think there was a way of doing a drama from multiple perspectives like that about World War II?’ I thought this was a very stupid idea. And then like most stupid ideas, it kind of wouldn’t go away. So the real beginning was that. And then it’s interesting that you should mention the thing about ordinary lives. As that generation, you know, there’s very few of that generation left. The thing that niggled at me was how it especially in the United Kingdom, I think, that generation was given this kind of sepia-tinged definition by which they were no longer considered flesh and blood. They were almost considered saintly in their fortitude and so on. And I just think as a dramatist is far more interesting that people are flawed, people are flawed, and people do the right thing for the wrong reasons, the wrong thing, for the right reasons. So I wanted to kind of reclaim that generation as ordinary mortals, because I think that makes everything they did more heroic, not less.

Jace There is also a bit of a personal connection to some of these story strands, such as the dynamic between Lois and Connie.

CLIP

Connie We’re going to be late! We’re due at half past.

Lois Connie, we’re the glamour. They expect us to be late.

Connie The glamour need to run for the bus, so, in your own time!

Jace What was the Two Shades?

Peter My grandma on my mom’s side was a variety artist in the north of England in the 1930s and 40s. And she was in a duo with the woman I grew up calling, my Auntie Anna, who was a British Afro-Caribbean woman raised in Doncaster in the north of England. She became a variety artist, and they joined together and called themselves the Two Shades. So they became a point of entry really for telling the story because they both were they. They formed an all women’s swing band in the war called Victory Vees and they drove ambulances in the north and in the Northwest Blitz and combined that with performing. So it’s a gift that you’re not going to turn down and it’s a way in. And I knew what my mum’s vernacular was, so I kind of capture something of their vernacular. So that’s how that’s where the Two Shades came in. Clearly, they’re not those women, but very much influenced by those women.

Jace I mean, there is an international cast of characters here. You’ve got Brits, you’ve got Germans, French, Algerians, Poles, Senegalese, Americans. How did you go about selecting these specific nationalities and sort of divvying them up, as it were?

Peter Yeah, well, I think that the Polish story, at least in the United Kingdom and I suspect also here in the States at the beginning of World War Two, hasn’t really been told the way it comes across in history lessons in the U.K. is that the Poles rather inconveniently got themselves invaded and then we had to help them out. And the fact that we call that period from September till after Christmas, the Phoney War indicates that, you know, the Polish experience was pretty much written-off. So both from a dramatist point of view, there’s material there that hasn’t been used or done. And also from a kind of moral point of view, of a telling of World War II, why not center on Warsaw? And why not center on those aspects of Warsaw that we find surprising now, which was that Warsaw was a great place of great architectural beauty that was seen as on the par with Vienna and Paris, an old school, European capital you know, because you go to Warsaw now, and obviously because it was bombed to hell, you know, the buildings are all kind of that post-war, Soviet architecture, you know. But also, you know, there were young British civil servants there. It seemed like a kind of too rich a seam not to start mining. So the Polish thing pretty much was place itself.

Jace You mentioned that the cosmopolitan aspect of pre-war Warsaw. The first episode does begin as a love letter to that city, to young love to the possibilities of Europe before the Second World War.

CLIP

Harry I have just had supper with a Polish family, sir, and I can’t stand idly by as the Polish people are invaded!

Walker That’s very noble of you. I’ll lend you my revolver. Good luck.

Harry We have to do something!

Walker We do indeed. I have to get a good night’s sleep and you need to sober up.

Jace What was your intention with this idyllic beginning to World on Fire — to offer a contrast with the horrors that were yet to come?

Jace Yes. And I think going back to my original intention of reclaiming that generation and showing how until war broke out, their concerns were identical to every young generation before and since. And definitely, I mean Adam Smith who directed that, directed it beautifully in it. I wanted to have a heightened feel, a slightly non-realist feel, because for us to feel the loss anew, I think, that it was to help that to be achieved. And I also wanted parts of clearly making Harry forgivable in terms of his love for two women. I kinda wanted to say to an audience, ‘Look at where he is and look at who he’s with and you know, are any of us better than that?’ you know? And look at his home family and look at this family that welcomed him. You can see how he has been seduced.

Jace By kindness.

Peter Yes, by kindness.

Jace There is a sense within World On Fire that life goes on even during the terror of war. When asked what she prays for, Kasia says, ‘Crayfish and sugar.’ Is that meant to be reassuring that the human spirit is in some way elastic and people can live their lives even during wartime?

Peter Yeah. I mean, I think I I find it to be true, but when I’ve researched it, I find it to be true that our concerns don’t change. I actually read a diary of a young Polish girl who was a waitress in Warsaw. And, you know, most paragraphs were about coffee and boys. And then there’d be something saying, ‘I joined the Resistance today. It’s run by the local scoutmaster.’ And just, I mean, obviously, for a writer, that detail is, well that gives you the jump off point. But, yes, Richard Overy, who’s like the overall historical adviser, is a brilliant and very highly respected academic expert on World War II, one of his first concerns was that he said, ‘Don’t try and make everybody sit around, talk about the war all the time. It just didn’t happen.’ It didn’t happen, because our overriding concerns about emotional lives will always blot out the worst horror. When I was doing Occupation, I was talking to a journalist about what happened straight after a bomb attack or something in Iraq. And she said there’d be silence. And then the shutters would go and people would start selling things, almost immediately. The push to get back to normal. The push, the push. So I wanted to capture some of that. I think.

Jace It’s Harry who in many ways knits these characters and their storylines together. If Harry is not the hero — and I’m saying I’m using that in air quotes here — If he’s not the hero of World on Fire, is he the great connector.

Peter Yeah, I think that Harry and to some extent. Nancy, because journalists of that era are something of a gift to a dramatist because they can move around. And so she does provide some connective tissue between both Harry and Kasia. And between Webster in Paris and his kind of personifying the American experience at that stage, I think. But yes, Harry is very much, on the tube map he would be Oxford Circus if that translates?

Jace It does, yes.Peter Everything runs through Harry. Yes. And it was always at three when obviously the first question when I was pitching this was, well, how do you stop it just being a scattergun, so it’s a thing, as a series of events. And one of these was this love triangle and particularly through the route of Harry, the other was we would occasionally see one character who we’d already established kind of pass on the dramatic baton to another character, but at least we as the audience thought, ‘Oh, right. He’s that mate of Tom’s, or he’s that mate of Douglass’s or she’s somebody who sings with Lois,’ so it was those kind of, those connections. And thirdly, in terms of action reflecting on other actions. So Harry might be caught up in some military battle at the same time as Kasia caught up in the battle trying to assassinate a German occupant, or whatever. So those are the kind of throughways, I would hope. And my main faith, though, I have to say, is that television audiences are incredibly sophisticated now.

Jace Before this next question, let’s take a quick break for a word from our sponsors…

Jace We see the battle of the River Plate on the HMS Exeter through Tom’s eyes. There’s a story between Tom, Vick and Henry that ends in tragedy.

CLIP

Tom I know it won’t go far, but you know, you need it more than me, so.

Henry Thank you for seeing me right after what happened.

Tom Don’t tell anybody I’ve done this.

Henry Yeah, I’ve heard they been giving you grief about keeping it.

Tom Yeah, well I’m not doing it for the lads, I’m doing it for Vic. It’s the sort of soppy thing he’d do, innit it? This doesn’t make us mates.

Henry No. Thank you for the money.

Tom Yeah, maybe you could put it towards a hook?

Jace What was your aim with these three?

Peter Well, I liked, I think, I liked the idea of connections being hastily forged. You know, men are away. They volunteered. And then in battle, you finding else out about yourself. I think all my work explores a certain kind of masculinity to do with denial of feelings, or showing feelings being weak. So it’s kind of trying to put that to the test in the most extreme circumstances. And I’m rather fascinated, I like Tom. I like that he does not want to be seen to do the right thing, even at a cost to him.

Jace To himself. Yeah.

Peter Because there’s part of Tom, I think deep down that thinks, ‘I’m not good enough,’ and has something to do with this relationship that we see later on with his father and how he feels his father feels about him. But the other thing I want to do was, I like, the roughness of showing his understanding, so even when he’s giving the money to Henry, he can’t resist making a joke about, ‘You could put it towards a hook.’ Because he can’t be seen, he sees being kind as being weak. The other thing that was fun to write the strand but all that together in a weird way was the canary story.

Jace Mm hmm.

Peter And I was reading — well, I was reading, in terms of research. What so many people wrote and kept personal logs and wrote incredibly well, actually. And I think it wasn’t the captain’s log in the Exeter, but it was somebody junior to him, wrote, just there was one detail. It was, ‘After the after we were hit and we retreated. We found out after the heat of battle that the ship canary had laid an egg’ and I just left all that when you read it, that’s kind of the detail look at, I built the whole story around that. So what would Tom be like? Well, he’d be the one to run a book and make a few quid and run a scam. And then so that whole thing about the money. And then I’m keeping the money even though these guys have died. And the more, you know, the moral the whole morality tale is carried by the canary story. And that’s for me, interesting.

Jace There is a bit of gallows humor to this moment. How did you approach the inclusion of humor in terms of writing you know what is ostensibly a World War II drama?

Peter Well, partly I can’t help it as a writer. I can’t help it. What I observe is people are always quite funny under duress and in the dark. You know, I did it in Occupation. And it’s the same thing. The real challenge is walking the line between making jokes that are true to the time and aren’t just rather nasty, racist, homophobic or sexist gags for the sake. You don’t want everybody in the drama to be mysteriously woke in our own terms in 1940, but nor do you want to indulge a kind of, ‘Oh, look, we can get away with making racist jokes because it’s a period drama.’ I think with Tom as well. Look, what’s massive for Tom is that he will always deflect with humor, but he will always deflect with humor or his version of humor. And his version of humor is pretty dark and pretty savage. So that would be the tone of the day. Again, in the terms of, in one of the descriptions, so losing their arm in that battle in somebodies diary, it was like somebody said, ‘But we put a tourniquet on and he was soon smoking a cigarette.’ And then I saw a picture. I think I saw some photographs of the Exeter after it got support and the damage. The claustrophobia of a sea battle, just frightens, it terrifies me. And this it looked like something on Doctor Who cause it’s just wires hanging down. You know that this improbable life force that we have that we could do it because I think I’d just be the guy weeping, you know that we can get out of this or do our best to get out of this or move. And the other thing that’s interesting about sea battles is you don’t know what’s going on anywhere else in the ship and you don’t really know if you’re winning or losing. You don’t know. And so that whole thing of getting on deck and then you see how many people laid out. That’s the first time you know, if you’re working below deck, that’s the first time you know. And that certainly is quite an extreme human predicament experience to write about. And I have to say Paul Spriggs, who designed it, so we built that ship, is just astounding. And the Navy, who helped, the Royal Navy adviser who helped him build it, couldn’t believe what he saw on screen. So it just didn’t feel full. It just didn’t feel like it. And I was more nervous about the sea battle than any other battles, because I think because ships move so slowly, it’s quite hard to have the edgy drama you have with an air battle or a street fight because they move slowly. So it’s a bit like going silent. Right. But 10 minutes later, it’s still turning. You know, it’s like, and then the torpedo and this is a cliche of naval battles. And I really think, you know, all credit to everybody involved in that. They really landed it.

Jace They pulled it off. I mean, it feels intense.

Peter Yeah.

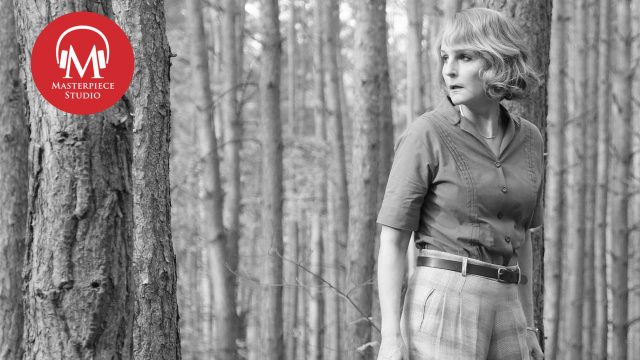

Jace Nancy’s able to stand up to Schmidt, her Nazi censor because of the power she has. But is there a sense that her power as an American, as a war correspondent, as a woman, is finite and can therefore be revoked in some way?

Peter Oh, yes. And I think in a strange way, I think the fact that she’s been a woman has both enabled her to get away with stuff because she’s underestimated. And then the very thing that’s enabled her to do that will come to be part of the reason she becomes more threatened. And she’s canny. And I wanted somebody who could kind of play the minder.

CLIP

Schmidt Well, I have an easy answer for you. There is no euthanasia programme.

Nancy Well, Hitler signed a decree in October so I would be surprised if that were true.

Schmidt The Fuhrer’s decree was for adults who may be enduring a “life unworthy of life.” No children were mentioned.

Nancy I’ve been to the clinic. I’ve stood outside and seen a bus full of children driven in. I’ve spoken to a mother whose child died in the clinic. I know the name of the head of the clinic. And I would like to meet him and talk to him.

Schmidt That wouldn’t be advisable.

Nancy Okay, then. I’ll just continue making a nuisance of myself.

Schmidt And then you will end up being deported.

Nancy And where will you end up as my official minder? If I’m makinga nuisance of myself, I wonder what that will do for your position in the Ministry?

Peter William Shera, whose diaries I read and whose broadcasts I read. He was in Berlin at the time and she’s an amalgam of him and two other journalists, in a way, said he was always surprised about what was allowed and what wasn’t. So they were quite happy for her to report on intimidation and deportation of Jewish people. But they weren’t happy that she reports on a shortage of carp, because that was the Christmas dinner at the time. So you could never quite gage what was going to be. And then he’d say, tone of voice, or you’d maybe use a phrase that Americans were more familiar with thanGermans. You get stuff through, but there’s a fair degree of collusion that’s unavoidable. And Helen Hunt was always on to me about that, she said ‘At what stage does she look like a collaborator? How do we make it not look like a collaborator?’

Jace I mean, her plotline also involves her neighbors, the Rosslers, and their daughter, Hilda, who has epilepsy. Did you seek to use the Rosslers to anchor Nancy more deeply into the fabric of Berlin or to, again, sort of offer a sense of humanity to ordinary Germans during the war?

Peter Yeah. I mean, both of those things. But mainly I wanted to write about what it is to be apolitical and live under a Nazi regime or live under the right-wing nationalist regime and hope things will change and then find out they’re not going to change. And then they have this thing that marks them out. There’s a whole floor in the Imperial War Museum in London given over to the Holocaust. In the corner is one small section on this eugenics program and that being at one of the things the Nazis did, of course, was they recorded everything. They photographed everything. So there are pictures of distressed children who’ve just been taken to this clinic under the guise of treatment. And I just remember seeing that, and thinking, I’ve got to write this. And it gives the family a secret. And it gives Nancy a wrong-footed crusade. Because the more she reports, the more exposed they are. And so it had the right degree of ambiguity as well. She’s doing the right thing. But she’s not actually doing the right thing. And her instincts are good, but what she does is she makes it worse for the Rosslers.

Jace It’s Jan who tells Robina about Harry and Kasia’s marriage during an English lesson.

CLIP

Robina That’s Harold. He’s Harry’s Father. My husband.

Jan My Father. Husband.

Robina Ah, yes…very good. Your Mother? Wife.

Jan Harry. Kasia. Husband, wife

Robina No, Robina and Harold. Husband and wife.

Jan And Harry and Kasia. Husband and wife.

Jace Did you always know that this would be how Robina would find out about the two of them?

Peter You know, that possibly might well be the first scene I wrote for the whole…

Jace Really?

Peter Seven hours. Yeah. So, yes, I did know and I knew it would be a good scene. So that’s where you start. Sort of cherry-pick some of the nice stuff. Um, because I just like the idea this boy who’s been patronized by everybody knows that he’s the one with knowledge. So I always knew it would come out like that. And I think, well, the young lad who plays him is extraordinary. And their dynamic and in. And later on, Sean Bean’s dynamic with the kid is just the just phenomenal. But, you know, Robina’s a woman of great certainty. So. With a character like that, all you keep doing is keep puncturing that certainty. Yeah I love that scene.. I love how they did it, not just the writing.

Jace Kasia can’t go through with the assassination of Clouse Rossler. She tells Tomasch that he wasn’t like the German who killed her mother. What stops her exactly? Is it the invocation of his sister, Hilda’s name, his kindness to her or something else altogether?

Peter I think a combination of those. But I think mainly he inadvertently manages to humanize himself. And then it becomes harder to kill somebody because you see their humanity, even though he’s wearing a German uniform and he’s fighting for the Nazis that his is kind of. guileless jabbering about his sister and he’s nervous and all the rest of it. I think deep down, she hopes somebody somewhere would be as kind to Gregor if he found herself in similar circumstances. And the story has to be about her gradual hardening. Because Kasia’s story in a way is about somebody who in fighting for humanity, loses her own humanity.

Jace And we see that in this episode, by the end of the episode, she’s very willing to lead a German officer to his death after they see Ludvig is murdered. I mean, has her humanity been taken from her at this point? Or does she still at this point in the series, retain some shred of that?

Peter Yeah, I think she has to batten down any feelings or misgivings. Well, I’m interested, what does it take to kill somebody? I don’t believe it’s something we do naturally. I don’t think that’s what we want to do. So what is it that allows us to do that when we think it’s the right thing to do? So she’s interesting in that respect, and there’s a point at which, further down the line, I think she does harden even more. And then that kind of comes back to bite her. So this whole thing opens up. Kasia is too wonderful to ever be lost to humanity.

Jace There are four episodes left at this point. In the broadest of terms, what can you tease about what’s coming up?

Peter Well, we have the retreat at Dunkirk. And I’ve tried to tell that story, which is very familiar, I wanted to tell it in a slightly different way from a slightly different point of view. It also provides the opportunity in the series for a number of characters who we, the audience know, all being in the same place at the same time, even though they don’t know each other. And then we have the fall of France. Harry’s decisions around Lois, because he returns home, and we push on to the climax of the Rossler story, and the climax of Nancy’s intervention in that and Webster and Albert once France has fallen, what life would be like for Albert in particular once Paris has fallen, and leading up to the climax of the series.

Jace Peter, Bowker. Thank you very much.

Peter Thank you. It’s been lovely. Thank you.

Jace One of the unexpected breakouts of Peter Bowker’s sweeping World On Fire is the smart, no-nonsense jazz singing factory girl, Lois Bennett.

CLIP

Robina Does Harry know?

Lois Yes, Harry knows, and I’ll say the same thing to you that I said to him: I don’t want or need anything from you.

Jace We’ll speak with series star Julia Brown on Sunday, May 3, here on the podcast.

World on Fire Podcasts 11 More Podcasts

MASTERPIECE Newsletter

Sign up to get the latest news on your favorite dramas and mysteries, as well as exclusive content, video, sweepstakes and more.