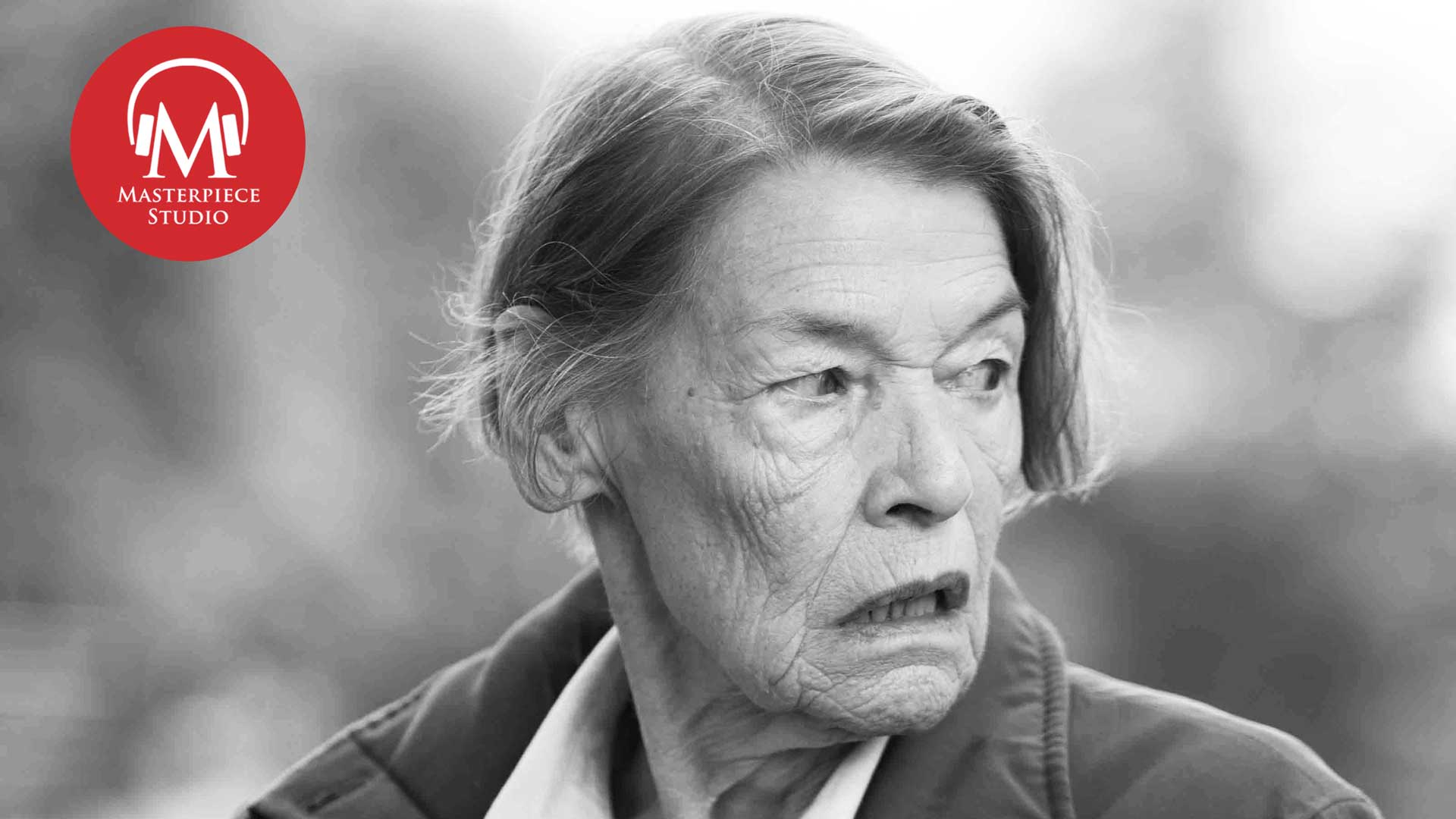

It’s not many actors who can appear in the very first season of a television anthology series, win not one but two Emmy Awards for the role, and then take a 50 year break before coming back for more. Glenda Jackson is one such actor, and her appearance in Elizabeth is Missing is just as powerful as any other in her storied career. Jackson talks politics and passion in a new podcast interview.

Glenda Jackson Returns To MASTERPIECE, As Gripping As Ever

Released 31:19

Related to: Elizabeth Is Missing

Download and subscribe on: iTunes | Spotify| RadioPublic

Transcript

Jace Lacob: I’m Jace Lacob, and you’re listening to MASTERPIECE Studio.

As MASTERPIECE launches its 50th Season, it’s only appropriate that the first title that greets viewers stars one of the most accomplished actors of any generation: Glenda Jackson.

CLIP

Elizabeth Maud, don’t do that, you’ll get dirt in your fingernails. Use your gloves.

Maud No. You don’t need gloves. You just put soap under your nails.

Elizabeth Who told you that?

Maud Helen. It’s an old gardener’s trick.

Elizabeth Well helps if you remember the soap.

Jace Jackson, of course, is no stranger to MASTERPIECE — her turn as the titular Queen Elizabeth the First in Elizabeth R from the opening season of MASTERPIECE Theatre earned the Academy Award-winner not one but two Emmy Awards.

CLIP

Glenda Jackson I mean, I just couldn’t believe that I had seven months work. It was just amazing.

Jace But Jackson’s return to the screen after a 27-year absence is quieter, subtler, and more than a little melancholic. In Elizabeth Is Missing, Jackson stars as Maud, a vigorous woman of a certain age, who finds both her best friend and her memory increasingly and distressingly absent. As she investigates the disappearance of her confidante, Maud begins to unravel not only what happened to Elizabeth, but also the 70-year-old mystery of what happened to her sister, Sukey.

CLIP

Maud I’ve got to find Elizabeth. She’s not answering her door. Something must have happened to her. Her blinds were closed. In the middle of the day. That’s not like her.

Helen She must have gone away.

Maud She has not. She would have told me.

Jace Naturally, Jackson has already won a BAFTA and an international Emmy for her role in this production, and the multi-hyphenate, multi-award winning actor and former British MP graciously joined me to discuss memory, Maud, and Margaret Thatcher, among much else.

Jace And this week we are joined by Elizabeth is Missing star, Glenda Jackson. Welcome.

Glenda Thank you.

Jace Elizabeth is Missing lured you out of retirement from the screen. Why was this project written by Andrea Gibb and based on the book by Emma Healey, the one that brought you back to the screen?

Glenda Well, it was the one that was offered to me. I mean, I had done two plays, both in London and New York. And then the script was sent to me and a copy of the book. As the issues of dementia and Alzheimer’s are something all Western democracies are having to come to terms with, we are remarkably unprepared for these diseases. And as we have societies who are living longer and longer despite the coronavirus pandemic, we really do have to begin to examine how we care for ourselves as we live longer.

Jace I mean, you have been outspoken on this issue, of how we can fund that care that an elderly population so desperately needs. I mean, what about this project therefore then spoke to you on that deeper, more profound level?

Glenda Well, it was an extremely well written book. I mean, based on the author’s experiences with her own grandmother, it was a good script. And it is an issue which I think is of importance to the whole of society. How do we look after ourselves when we get beyond the age where in the past we would have been expected to die?

Jace I mean, In Britain, the NHS defines Alzheimer’s as an incurable disease, given, as you say, that we are living longer as a population, what conversations do you hope emerge as a result of Elizabeth is Missing both in terms of the funding and health care research itself?

Glenda Well, our present government is talking about but this is as a direct result of the covid pandemic, about care homes for the elderly. We just have to wait and see if they actually deliver rather than welp and just chat about it, but we as a society have to acknowledge that, as I said earlier, we are living longer. And those illnesses, which are now part of our society’s growth in a way, were not there before. And we have to acknowledge that indeed our NHS says that Alzheimer’s is incurable. That doesn’t mean to say that it isn’t possible to live with an incurable disease. But the requirements of how you care for those people is something which I think as a society we have to accept responsibility for.

CLIP

Maud Thank God. Somebody with some common sense. Are you out looking for her now?

Desk Sergeant Yes we are. We’ve got every man in the Force out. And the Flying Squad. And the sniffer dogs.

Maud Dogs, they won’t hurt her, will they?

Desk Sergeant Like I told you yesterday, they’re nice dogs.

Maud Yesterday? Was I here yesterday?

Jace After almost three decades away from filmmaking, what struck you is the biggest change in terms of the process?

Glenda Oh, the technological exchange. I mean, in my day, you know, you would rehearse and then you’d go away for anything up to four hours and go back and shoot the scene. Now the technology arrives in the box. And I saw a box open and I think there were eight to ten different lenses in it, which screw in, I mean, just the technological speed with which films are made now, and that people were watching, you know, beside as you’re actually doing the scene.

Jace You’d returned to the stage before Elizabeth with Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women, for which you won a Tony Award and with King Lear, where you played the titular role opposite Ruth Wilson as Cordelia and the Fool. What did it mean, particularly as a woman, to take on the role of Lear?

Glenda It was just such a privilege to be allowed to do it. A friend of mine, a wonderful Spanish actress, had done it in Barcelona. And I went to see it. And she said to me, ‘Why don’t you do it?’ And I said, ‘They’d never let me do this in England,’ but God bless the Old Vic, they did. And it’s such an extraordinary play. I mean, it’s just amazing. The gender aspect of it didn’t really feature as far as I was concerned, and I don’t think it did as far as the cast or the audience were concerned. It’s just such a magnificent piece of writing. You know, human nature doesn’t change — the human condition, it can be improved, but we don’t change that much.

Jace We don’t, it’s true. You’ve won two Academy Awards, two Emmy Awards, a Golden Globe and a Tony. You’re one of the most celebrated actors of all time. You left behind the world of acting for a career in politics as a Labour MP. What was behind the decision to leave acting behind?

Glenda Essentially because of what the Thatcher governments had done to my country. I mean, I have been an active member of the Labour Party and have been approached by a couple of constituencies. And then when I was approached by Hampstead, which was where I had lived not that long ago, I thought, yes, go on, have a go, because I was seeing my country simply being subjected to an overwhelming sweep of decisions that I thought undermined, I still do, what is essential about the United Kingdom. It took us five years to get the Labour Party post-Thatcher’s departure to get into government. But I think we did bring about many things that were transformative, all of which, destroyed, of course, by our going into the Iraq War.

Jace I mean, you gave a blistering indictment of Thatcherism in Parliament in 2013, speaking about, quote, ‘Sharp elbows, sharp knees. All these were the way forward.’ What has the Covid pandemic revealed about society and community, about not leaving people and walking by on the other side?

Glenda How unfair a society we live in, but how that doesn’t actually match what the citizens of our society feel. I mean, the amount of unstinting work that has gone into the actual treatment of Covid patients, but also the sheer generosity of people who, you know, organize food banks, who help people who are on their own, that sense of a community having something to contribute, simply having said, you know, human nature doesn’t change. Well, that’s one of the marvelous things about human nature that doesn’t change — that compassion and caring and a sense of unity with a fellow human being has been enormously powerful during this pandemic. And let’s hope we learn the lessons from it.

Jace You’ve said of that impassioned speech in the Commons, quote, ‘I had to speak out to stop history being rewritten.’ Is that statement even more relevant in today’s political and social climate?

Glenda I think we’re in the middle of it too much to be able to make a judgment there. I think the actual day to day, almost hour by hour sequence of what not only our society is going through, but certainly when one looks at America and sees the numbers virtually going off the wall of covid victims, but hopefully we will learn from it. As I said, I think it has illuminated for those people who weren’t aware of it, of how divided, I think economically, mostly our society in the United Kingdom is, and let’s hope that those lessons will be learned and restructured for the future once we’re out of it.

Jace Before this next question, a brief word from our sponsors…

Jace Elizabeth is Missing is a double mystery where Maud investigates her friend’s disappearance while also solving the disappearance decades ago with her sister, Sukey. But it’s also a powerful exploration of how we treat the elderly, particularly those with dementia. Which element did you find most compelling?

Glenda Well, I don’t know if I already said this, but we had the meeting myself, the producer and director with one of the directors of the Dementia Society, and I had found in Maud’s character how she, due to the illness, of course, seemed to be transformed from a balanced, loving, kindly mother, grandmother, neighbor, how to put it, to this virago. And I said to the doctor, ‘Where does that come from? What is that?’ And she said, ‘Frustration.’ And that I found immensely helpful that I could understand.

Jace Maud is such a compelling character, she’s struggling to reconstruct a narrative as her memory slips away. We see her in moments of clarity and moments and confusion, in good humor, such as when she says she’s hiding from the wolf, and in anger. I mean, given that, how difficult was it to construct her character, to ground her?

Glenda Well, it was an extremely good book. I mean, the script was excellent as well. The cast and crew. So having taken on board that sense, there is a line in the film where she says, ‘I have this feeling inside me and I want to share it, but it won’t come out.’ So that was helpful in being able to, well, she didn’t switch, but I mean, one could understand, the varying world that she was inhabiting, not only day by day, but sometimes hour by hour, minute by minute.

Jace I do want to talk about that scene.

CLIP

Maud I know what you’re thinking. You think I’ve lost my marbles and I’ve just forgotten. Well, I haven’t. She hasn’t got her glasses, her blinds were shut in the middle of the day and I haven’t lost me marbles. Though everybody seems to think I have. Nobody listens to me! Am I invisible or something? Oh no. Still here. I want to scream.

Helen Mum…

Maud Don’t you ‘Mum’ me. I want to scream but it won’t come out. It’s all stuck in here. All the feelings are in here.

Katy Gran…

Jace Her profound pain in that scene struck me in such a visceral way. What emotions were you channeling during that scene?

Glenda I mean, I can’t answer a question like that because it’s got nothing in the strange way to do with me. It’s it’s what I do. I mean, that’s what acting is.

Jace Do you see yourself then as sort of a vessel?

Glenda How did you mean?

Jace Through which the sort of character emerges?

Glenda No, no, I mean, as I said to you, you have to see the world through the eyes of the character you play. That’s the image that you have.

Jace It’s only later that Maud finds her voice and actually does scream and she lashes out at Katy with the newspaper and she’s actually howling for the first time. Is this moment a release for her to express this anguish, this pain?

Glenda At the moment that she does it, she is not aware that she is doing it to her nearest and dearest, they’re just the people in the hall. But her illness is not progressed so far that she is not aware of it having happened, if you see what I mean.

Jace I mean, Maud to me is the very definition of an unreliable narrator because we, and even she, cannot trust her memories or the information she’s providing. But the way it’s presented is not sensationalized in any way. It’s presented very matter of factly. What was your take on the film’s lack of sentimentality?

Glenda Well, it was a big plus, wasn’t it? And I don’t agree with you that she remembers factually. What she is not aware of is that the time she’s in at the moment is not the time she’s remembering.

Jace No, that’s true, I mean, she does uncover the memories she finds. What happened to Sukey. She’s able to make these discoveries by piecing them together, by becoming a detective of her own psyche in a way. I mean, her motivation in the narrative is to find Elizabeth, to reconnect with what might be the most intense emotional and physical anchor in her life, her best friend. How would you define the relationship between these two women and its importance in Maud’s life?

Glenda Well, it’s clearly very, very important. And also, Elizabeth is very supportive because she is aware of Elizabeth’s illness, actually, even though it’s at the beginning stages and then she herself becomes ill. But. I mean, to go back to what you said earlier about Elizabeth being a detective, she isn’t a detective at all because one of the things that runs throughout the story is her inability to understand that her concerns about Elizabeth are not shared by those people who are closest to her. She’s still concerned with finding Elizabeth. Even though she has been told, do you see what I mean, she’s still living her, her perception of what has happened.

Jace I mean, the only person who even believes Maud slightly as she begins to look into Elizabeth’s disappearance is her granddaughter, Katy. And I love Maud and Katy’s scenes together. What is the dynamic between grandmother and granddaughter like here?

Glenda Well, I think grandmothers and granddaughters can recognize it. I think one of the shocking things is when she turns against her granddaughter, when she doesn’t recognize her.

CLIP

Katy I’ve made some hot chocolate.

Maud You want to have a word with that one. That girl you’ve hired. She’s not doing what you’re paying her for.

Katy It’s me, Gran, it’s Katy.

Maud I don’t give a snuff what your name is. Get rid of her. She’s lazy.

Helen Say sorry now. SAY SORRY.

Maud Sorry. Sorry. Though I don’t even know what I’ve done!

Jace I mean, to me, that’s one of the most heartbreaking moments in all of Elizabeth is Missing, are those scenes where she doesn’t recognize Katy or Helen and lashes out with frustration at them, which is a real reality for families dealing with dementia patients.

Glenda Absolutely, it is.

Jace How difficult were those scenes to film in their sort of honesty and brutality?

Glenda Well, they weren’t that difficult because, as I’ve said, it was a good script, they were good actors. And we all knew what it was. So I would say difficulty was part of it, no.

Jace Maud is a creature of habit, writing things down on Post-it notes to jog her memory, sticking to the same routines. It’s the disappearance of Elizabeth that upends that orderly existence and sparks these long buried memories of her sister Sukey. Do these things open up her long buried memories even as she drifts deeper into a cognitive miasma?

Glenda Not really, because she holds on to her version of events, and she refuses to be taken away from that. She has a villain of the piece. She has her own theory of what has happened. So this, again, is an element of what the disease does to the brain.

Jace How much of a struggle was it to leave the character of Maud behind at the end of the day? Do you ever bring the work home with you, or the second they say cut is that it?

Glenda There’s always. Well, I mean, you know, you shoot a film in short chunks and not necessarily in the actual time frame that the film will adopt. But it’s always, there’s always something at the back of your mind that’s fretting around something or wondering about something.

Jace We are currently living through a global public health crisis that is only further isolating people, particularly those in highest risk groups like the aged. What conversations do you hope that Elizabeth is Missing generates around social care or a sense of community for high risk individuals like the elderly?

Glenda Well, I think it’s very difficult to move away the direct danger that we are in with this covid pandemic, but once the pandemic begins to withdraw its dangers, if the vaccines get spread out, as I said before, I think the issue of how we as societies deal with these illnesses that are not going to go away like the covid virus they are dependent upon comprehensive care, but care, that is more than just feeding and keeping clean, if you see what I mean, it’s it’s care in the most human sense, what caring is about. And we have to acknowledge that this is in the future and we have to be prepared to fund it, to learn about it, to be able to deal with it as a society, not as the exclusive responsibility of families who are having to deal with it even as we speak.

Jace You are living in the basement flat of your family’s home in Blackheath. What has the last year been like for you in the era of covid related lockdowns?

Glenda Well, I mean, it’s been in lockdown, out of lockdown. We’re going to go in to tier three from tomorrow. So one’s entrances and exits are limited to the back door. Fortunately, we’ve got a garden and certainly if I can get into a garden.

Jace I’ve heard that you are a fan of television, particularly lately shows like Schitt’s Creek and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, two of my personal favorite comedies of recent time. What are you watching and loving on television right now?

Glenda Well, I would certainly watch Brooklyn Nine Nine, but I’ve seen all the episodes. I have to get my grandson to fix my television so that I can watch Schitt’s Creek, which I saw only in America. I’m much more because of this, I think, and, you know, our television is very repetitious at the moment, more of a radio person.

Jace What are you listening to on the radio?

Glenda Mostly Radio Three, because that’s the kind of music program. But then there are the news programs on the radio and things like that. So, yeah, it’s varied, it’s interesting.

Jace What do you recall of filming Elizabeth R? Did you feel at the time that this would go on to become an internationally celebrated production?

Glenda No, not still. I mean, I just couldn’t believe that I had seven months work. It was just amazing.

Jace What was the high point of that production for you?

Glenda I think in a curious kind of way, it was, I think, the very last episode when she’s dying, and the director had wanted me to be sat in a chair holding the scepter. And someone, I mean, people had sent me books about Elizabeth through the whole series, but there was one that I found particularly fascinating, which was the diary of one of the ladies in waiting, who had said that she refused to go to bed. She would sit in the chair and all her ladies would have to stand around her, and that upon occasion she would suck her thumb. And I thought, that’s much better than the scepter. So we agreed on that.

Jace A wise choice. You famously shaved your head to play Queen Elizabeth in Elizabeth R. How much of a daunting commitment was this to make for the role, particularly as an actor in 1971?

Glenda Didn’t bother me.

Jace Just to, just to shave it right off? That’s amazing.

Glenda Well, I mean, only the forehead, I wasn’t completely bald. At least I had a bit more of the kind of forehead that she had. Would that I have her intelligence.

Jace Would that any of us did. Elizabeth R ended up winning Masterpiece Theatre five Emmys, and was the first international show to win the Emmy for best drama series ever. MASTERPIECE is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary, and to me, it’s fitting that Elizabeth is Missing should kick off its Golden Jubilee season, it sort of bookends these 50 years, you have, Elizabeth R in the first season and you have Elizabeth is Missing 50 years later.

Glenda Two very different Elizabeths.

Jace Two very different Elizabeths.

Glenda Very.

Jace How aware were you of the US broadcast of Elizabeth R on Masterpiece Theatre back in 1972?

Glenda I wasn’t at all aware, It was, I mean, it was shown around the world, mostly in public broadcasting services. I remember one check I got. I think it was from Nigeria for nine pence.

Jace For ninepence!

Glenda Yeah, well, fair dues. It’s public broadcasting.

Jace Why do you think that American audiences are so hungry for British television content? What does it say about viewers in the states and what does it say about American perceptions of Britain or Britishness?

Glenda I think they may still have a slightly romantic view of my country, but America having, I remember Hollywood fighting the advance of television all those years ago. They could see where it was going. But American television has transformed television. I mean, think of the shows that have been done that came out of America, the transformative change in television has undoubtedly come and I think from America. Not just the technical, transformative nature of it, but the actual subject topics that they dramatize or comedize, you know, just amazing.

Jace You were the eldest of four daughters growing up in northern England in a two up, two down with an outside toilet. Your father was a bricklayer. Your mother worked all sorts of jobs. What did your parents make of your choice to pursue acting as a profession?

Glenda My mother’s major concern when I used to go home, having done, you know, been acting, she always examined my shoes to see if they had holes in them. She was convinced that there would be holes in them. Sometimes there were.

Jace Your parents did come to see you in a play you did in Crewe. What do you recall of their reaction at the time?

Glenda It was my father’s reaction because as well as playing a small part, I was also the assistant stage manager. So when I wasn’t on the stage, I was doing things in the wings. And at the end of the first act, I think the character I played and the young sailor who was also part of the cast go off to the garden and they don’t reappear until the middle of the second act. And my mother said that, well past the interval between the first and second act, my father said to her, ‘What are they doing in that garden?’

Jace You worked in Boots for two years before starting at RADA. What did you take away from the experience of working in a chemist?

Glenda Well, actually, if it hadn’t been for the manager of the chemist shop, I wouldn’t have got to RADA. Because I did the auditions for RADA and I had to have a scholarship. And they wrote back and said, ‘If we had a scholarship, we’d give it to you, but we haven’t got one.’ And, you know, the management had asked me how I’d done and I showed them the letter. And the guy who was the manager wrote to the local county authority, Cheshire County Council, and said, you know, ‘I would have had this place in the drama school, but there wasn’t a scholarship. Would they give me one?’ And they did.

Jace So the council supported it?

Glenda Well, yeah.

Jace Yes. Amazing. The head of RADA told you upon graduation that you were a, quote, ‘Character actor who would not work much before 40.’ What did you make of that assessment? And are you still laughing now?

Glenda It was accurate, no it didn’t make me laugh at all. But then, of course, Look Back in Anger came along and the British theater changed, which afforded people like me and people from the provinces of the United Kingdom to have a place on the stage. It wasn’t limited to London and the middle class.

Jace But would you, I mean, what do you make of that term character actor? Aren’t all actors playing characters?

Glenda Up to a point, that’s true. But he was speaking within the frame of what was at that time. I won’t say British theater, but certainly Europe, even though the reps were closing, that we still had a wide range of repertory theaters in the United Kingdom. But the theater was essentially dominated by the West End of London, and that was what changed.

Jace What is next for you?

Glenda God only knows, hopefully an end to this pandemic so we can come out of lockdown, but we’ll have to wait and see.

Jace Glenda Jackson, thank you so very much.

Glenda Well, thank you.

Jace MASTERPIECE heads in a sunnier direction next, as our formal anniversary season continues with a bright, beautiful new version of the beloved book series, All Creatures Great and Small.

CLIP

Mrs. Hall Will you not stop for tea?

Siegfried I don’t care how he takes his Darjeeling. I want to know he’s up to the work. Come along Herriot, don’t just stand there.

James Are, are we not… I thought this would be an interview. I’ve got my references from the Principle of Glasgow Veterinary College.

Siegfried No. I’m no interested in a lot of flannel. Let’s get cracking. Until tonight Mrs Hall.

Mrs Hall Good luck.

Jace We’ll speak with series star Nicholas Ralph about heading to the Yorkshire Dales here on the podcast January 10th.

And stay tuned then for a special trailer of Making MASTERPIECE, our upcoming 50th anniversary documentary podcast, as well!

MASTERPIECE Studio is hosted by me, Jace Lacob, and produced by Nick Andersen. Elisehba Ittoop is our editor. The executive producer of MASTERPIECE is Susanne Simpson.

MASTERPIECE Newsletter

Sign up to get the latest news on your favorite dramas and mysteries, as well as exclusive content, video, sweepstakes and more.