This script has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jace Lacob: I’m Jace Lacob, and you’re listening to MASTERPIECE Studio.

There’s something unexpected about Sir James Danemere, both in character and circumstance.

CLIP

Sir James: Mrs. Chase, James Danemere. I understand you’ve been expecting me. I’m delighted to meet you.

Robina: Uh, um…

Sir James: You were expecting me, weren’t you? I hope this is the right house. It is Mrs. Chase, isn’t it?

Robina: I was told to expect you after Christmas. That’s what the war office informed me.

Sir James: Ah.

He’s charming, suave, elegant, and always knows just what to say.

CLIP

Robina: I have to say, I have no idea what the protocol or the social form is for this situation.

Sir James: Thank the lord for that! Neither do I. But if I can reassure you, I shall be mostly absent and when I am here, I endeavor not to disturb the peace.

Robina: Oh, I shouldn’t worry about that. Peace is in rather short supply I’m afraid.

But when Sir James recruits Kasia for a special mission, she’s able to see this charming artifice in a new light.

CLIP

Kasia: What will happen now?

Sir James: Well the best thing for her son is that we carry on as before; we make the drop, same time, same place. They won’t suspect a thing. And it’s a dead letter box. They have no idea what she looks like. You know, rather useful for us in fact, simpler.

Kasia: Simpler.

Sir James: Forgive me. She was your friend. Too easy to slip into war games. I apologize.

Kasia: You always know the right thing to say.

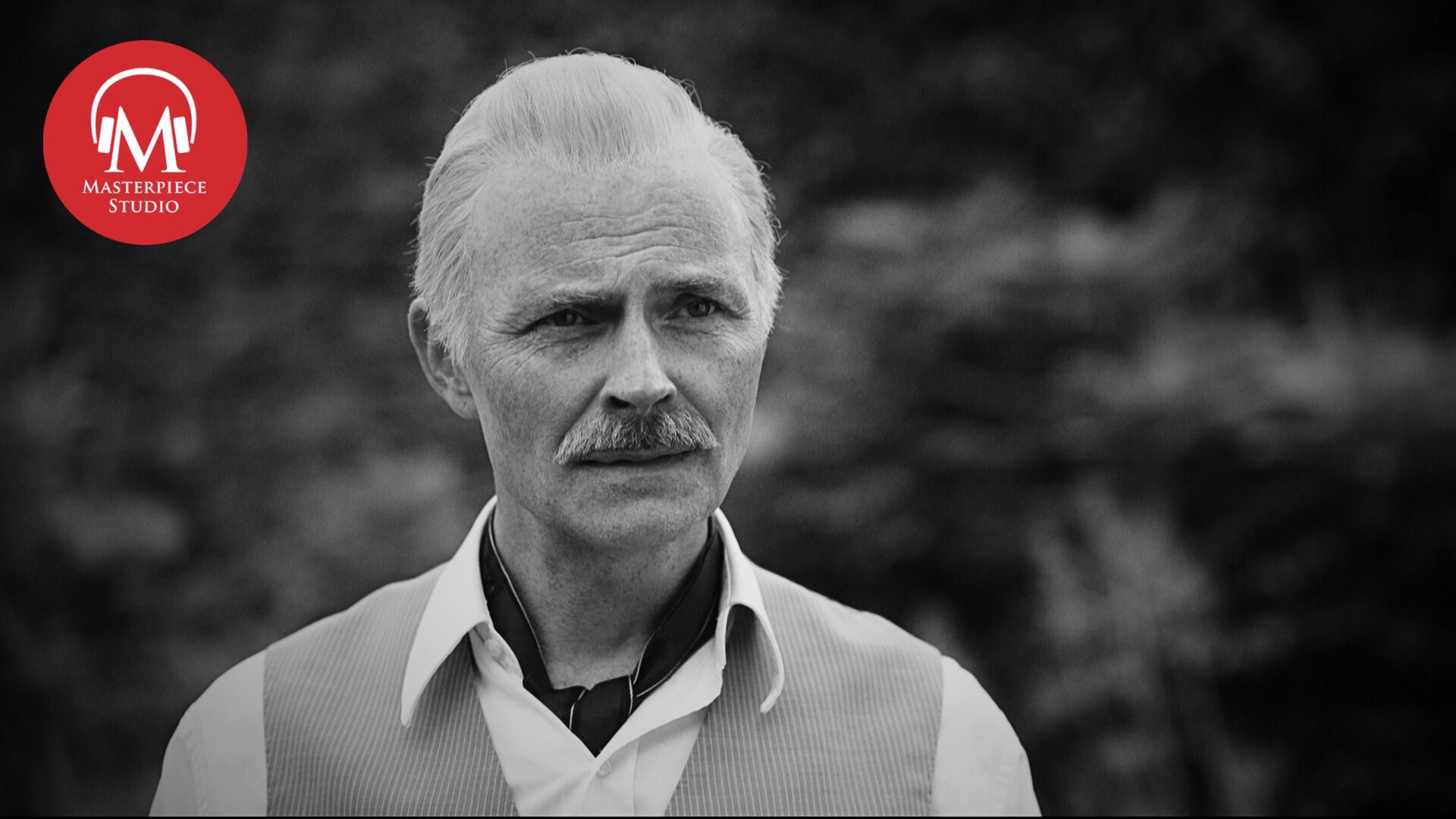

Actor Mark Bonnar joins us this week to bring us inside the head of Sir James, a man with a sharp sense of the ridiculous.

Jace Lacob: This week, we are joined by World on Fire star, Mark Bonnar. Welcome.

Mark Bonnar: Thank you very much, Jace. It’s nice to see you, meet you, hear you again.

Jace Lacob: Hear you, yeah. You’re playing Sir James in series two of World on Fire. He’s a new character for the second series. He’s a debonair MI5 officer bunking at Robina Chase’s home, who is introduced in the second episode. What was your take on the character when you read the script?

Mark Bonnar: What first struck me was his cheeky sense of humor, which I liked. He kind of ingratiates himself very quickly into Robina’s household. I enjoyed the relationship between the two of them. It’s not often that you see a burgeoning relationship between two people over 40 anywhere on telly really. I thought that was very nice. Those two things were the first things that struck me. Peter’s writing, of course, is marvelous and I’ve always wanted to work with him. So that was another attraction.

Jace Lacob: I want to go back to the script for episode two. I love Pete Bowker’s description for Sir James in that episode. He says, “He is well spoken, confident, but with a sharp sense of the ridiculous.” Is that the very epitome of a Mark Bonnar character perhaps?

Mark Bonnar: Do you know what? I hope so. Well, I don’t know about the well spoken, but, certainly a sharp sense of the ridiculous is, I would say, essential in whatever you do. Even if you’re a plumber or a daycare assistant or a police officer, I think a sharp sense of the ridiculous is always a good thing to carry with you.

Jace Lacob: Sir James’s introduction throws Robina onto her back foot. She’s not quite expecting him yet and she’s flustered by his very playful tone and he arrives with flowers and jokes that he should have brought two cabbages and a cauliflower instead, what with the war on. What does he make of Robina Chase in that first encounter?

Mark Bonnar: Oh, I think he’s quite struck straight away. But he arrives with a lot of responsibility and a lot going on. And it was a common thing for this to happen as well. This kind of thing happened quite a lot that people would be outsourced, important people high up in organizations like the civil service, would go and stay at people’s houses. They might not always have been like Chase Manor, but they were kind of shipped out from London, lest they came to any trouble, you know, they didn’t want anything to happen to the important people basically that were running the war.

So yes, I think he’s immediately struck by her, but he has another agenda on the go, but he knows how to charm. That’s one of his best weapons shall we say, is his charm and his guile and his, I think genuine bonhomie, you know?

Jace Lacob: You say charm, I think his other skill, which we later learn is accurately reading people, a skill that serves him as an intelligence officer quite well. This household he’s come into seems chaotic. Robina needs a stabilizing influence. Does he mold himself to become that for her?

Mark Bonnar: I don’t know if he molds himself to become that for her. I think it comes naturally to him anyway. For example, there’s the scene where he comes in and Robina’s in, which we’ve seen but Sir James hasn’t, she’s in the middle of an argument with the maid about changing the baby’s nappy.

CLIP

Robina: Oh for goodness sake Joyce! Please, let’s not recreate the Jarrow March over a simple request to change a nappy. Just do it, won’t you?

Joyce: I won’t be spoken to like that. You can stick it…bloody job.

Sir James: Joyce, do you know what I love about the house you keep? Always full of life. There’s always something going on.

Joyce: Well, I try to always give it a good shake, you know, like an eider down.

Sir James: Quite. Will you get your mother a bunch of flowers tonight? A treat from me for giving the world such a useful daughter.

Mark Bonnar: So I think he can very quickly come into a situation and diffuse. That’s another of his great talents, I think.

Jace Lacob: He injects a lot of humor into the series, but also stirs things up in the Chase household in very significant ways. But Sir James is also a bit of a fashion plate. He’s very sort of David Niven-esque, a bit of Errol Flynn, maybe. What did you make of his look and did you work with the costume department to create his very specific, very debonair style?

Mark Bonnar: Costume and makeup were fantastic. Costume came in with a very kind of strong set of ideas. And what happens when you’ve got a brilliant team is that they bring so much to the table that you can choose, the odd little thing, accessorize or whatever. I didn’t have too many strong ideas about the look that Sir James should have. I definitely wanted a mustache because I thought that would really suit.

When you read all the episodes, you have a picture in your head, not too strong a picture, but a flavor of the person in your head. So when costume brought all the different outfits to the fitting, they obviously are very brilliant at their job and straight away I was like, Oh my God, this is brilliant! You have good people and they do a good job.

I had a wig for it as well, which I hadn’t had before, which was a bit of a shock, but again, make up just does such a brilliant job. It’s kind of seamless. You can’t really tell. I almost asked for it actually when we left, I thought I could have this, you know.

The one thing that I love is detail which again, sort of hearkening to that, “always an eye on a sense of the ridiculous.” I wanted something that would just have a little tip of the hat to that. We always tried to keep that in mind. Although it might not be immediately obvious, it might be just the color of a sock or the way he wears a hat or things like that, or the way he holds himself. So for example when I first entered the show, when I arrive at the door and Robina opens the door, I said, can I face away? It’s a really quite dramatic entrance. He turns around while taking his hat off, his fedora off and introducing himself. And I just liked that idea of the kind of, you know, there’s a certain theatricality to him, of course.

Jace Lacob: I love that introduction, it’s just incredible. That’s amazing. Sir James, of course, isn’t who he initially appears to be. The first few episodes of Series 2 play around with the viewers’ expectations, as well as Kasia’s, seeing James as a potential enemy concealing secrets. He seems like a German spy, wielding what he dubs persuasion and influence. Do you see those as being his greatest weapons, persuasion and influence?

Mark Bonnar: Yes, I would say so. I’m not sure that he wields them in a kind of weaponized way. I think he sits comfortably with them in a kind of pipe and slippers way. He’s quite assured of his persuasive powers, and he’s quite assured of his influence in where he sits in the kind of theater of whatever it is, conflict. So, yes they are definitely two of the strongest weapons in his arsenal, but he’s not gung ho with them. He’s a quiet sort of subterfugey type, I think.

Jace Lacob: I love the dynamic between James and Jan and their sort of chess games.

CLIP

Sir James: You’ve been well taught, Jan. But you need to be more deceptive. Sometimes, it’s necessary to expose one flank as open to attack in order to trick your opponent into thinking you’re more vulnerable than you actually are. And then, you can spring the trap from the other flank.

Jan: You win by deceit.

Sir James: I win by guile that may or may not involve deceit.

Jace Lacob: Maybe not the most appropriate lesson to be teaching young Jan, or it could be the most essential lesson one could learn in wartime.

Mark Bonnar: Exactly. It could be. Eryk who plays Jan is just the most glorious lad. He’s got such a wonderful energy about him and we got on really well on set as well. I’ve got a daughter who’s about the same age as him and he’s just a great kind of presence, a great energy and we had a right laugh.

But yes, again, none of us know because none of us of our generation have experienced, well, many of us have of course, but not a world war, not on that kind of scale, obviously. There are wars happening everywhere at the moment, but in the West, that was the last great war and I think you don’t know how you would react or treat people or what advice you would give out or how it would change your perspectives until you’re there.

But I think it is a valuable life lesson. I think it might be tainted by the situation they’re in. But I mean, for goodness sake, poor Jan has seen arguably much worse than James has seen in his lifetime.

Jace Lacob: I want to take a step back. Like most Europeans, I’d imagine, you have familial connections to the Second World War. What sort of stories did you hear from your parents about your grandparents’ involvement in the war in India and Poland?

Mark Bonnar: Well, not much about India. Although, I recently said this to my mom, I was always under the impression her dad was in India and she said, I don’t think he was, I think he was in North Africa. And I was like, Oh God, I’ve been telling people all this time he was in India. But nevertheless, he didn’t speak much about it at all. But my dad’s dad, who was Polish, his brother, I hope I’ve remembered it correctly, but his brother was put in a concentration camp, I think.

My grandfather and his best friend decided to leave Warsaw and they walked all the way to Yugoslavia as it was at the time. And then got a boat to the UK and somehow made his way up to Edinburgh where there is a big and remains a big Polish community. And he met my grandmother and married her, had my dad. So that’s a very small snippet of one person’s life. But nevertheless, an extraordinary piece of one person’s life; to escape whatever fate they were worried about in Poland.

What’s wonderful about this show is that it reflects that. It reflects these incredible individual stories across Europe. I don’t know what it’s like in the States, but for a lot of the time, war stories were kind of told from our perspective. You write what you know, and people who were writing these stories were writing from a British perspective of the war. But, what Pete’s done wonderfully is he’s done that, but he’s also written from a human perspective, because we’re all them, and can relate to any person in any situation. And as it turns out, people went through hell everywhere at that time, you know.

MIDROLL

Jace Lacob: I think it’s interesting that World on Fire, it is sort of about large scale battles, but it is about these very small human moments. While Robina falls for Sir James’s easy charms and Jan for the attention he gives him, Kasia is another matter altogether. Sir James can’t quite crack her and she deduces his identity. What goes through James’s head in the moment when Kasia turns his own Luger pistol on him and reveals that she knows he’s military intelligence?

Mark Bonnar: It was a very interesting relationship because as you say, he couldn’t really crack her. She has a lot of, obviously everybody has baggage, it’s the war. Something has happened to everyone in the show. But yes, I think she brings with her that incredible journey that she went on in series one. And I think he sees a kindred spirit, but a troubled spirit as well. But yes, I agree with you. He’s kind of at a loss as to how to crack that particular nut. So I think she suspects the worst obviously. So I think to avoid any kind of further misunderstandings, I think he reveals himself and tries to get her help at that point. Yes.

Jace Lacob: And then he sort of begins to train her. So he instills this lesson in Kasia about utilizing a bland smile.

CLIP

Sir James: Miss Tomaszeski?

Kasia: Yes?

Sir James: May I ask, do you know what I mean by a ‘bland smile’?

Kasia: A ‘bland’? I don’t know that word.

Sir James: Flavorless, or in the case of smiles, meaningless.

Kasia: Like this? (smiles)

Sir James: Ah. You yourself know that Robina is the most acute of women. Keep hold of yourself. I feel she knows something is afoot. Oh, I know you’re an honest woman and this sort of thing doesn’t sit well with you. But try to think of it as an essential skill, rather than a defect of character.

Jace Lacob: Is he worried at this point about Robina figuring out what’s going on with Kasia, about Robina being suspicious of him? Is this just Sir James’s guile at play here? Is he just trying to smooth things over as best he can, having been caught in this situation and being forced to use Kasia now?

Mark Bonnar: Well, he works for MI5. So, if you’re going to work or be seconded to work for MI5, you have to work in secret. The more people that know, the more dangerous it is. So, yes, he doesn’t want Robina to know what’s going on. Robina sees Sir James with his hand on Kasia’s back and suspects the worst. So there’s a strange, unexplained chilling of the relationship between Sir James and Robina after that for a while.

Jace Lacob: I love his explanation of that, “I’m interested in her character and I can assure you that is all.”

Mark Bonnar: Yes. Yes. That’s right. Yeah.

Jace Lacob: Like in the garden picnic scene, which I love, James unloads this hamper full of champagne and foie gras, things that are very much not on the rations list. And he says, “Of course you mustn’t trust me, not an inch. You have too much to protect, Vera, Jan, Kasia, you’ve been left with quite the load.” And he does crack Robina’s armor here just a little bit. It is this beautiful moment between them. What did you make of the picnic scene?

Mark Bonnar: Well, logistically, it was quite tricky because we were in a location that was a second choice location after the first was discovered to be too wet, I think, because it had been raining overnight at this house we were filming. So we were kind of on the hoof a little bit and it was very windy as well that day. So you’re kind of battling with the elements a little bit. But nevertheless, I was really looking forward to doing that scene.

I can’t remember how many times, we did it quite a few times, but after the first couple, when we found the kind of emotional geography of where we were going to be, which is always what you do when do your first couple of takes, you’re trying each other out, trying things out, seeing what works. Maybe throwing a few things in. It’s just about being playful and unafraid despite the conditions, despite the logistical frailties of what was going on around us. It was lovely.

Jace Lacob: James begins running Kasia as an agent and provides her with her first target. She’s a Polish drafter, and Kasia manages to befriend the woman, only to learn she’s passing secrets to the Germans. And he suggests that she turn her, “Appeal to her shame if she has any. She is a traitor after all.” And then she ends up killing herself, and James is very pragmatic about it. “It’s all rather useful to us. In fact, simpler.” he says. Kasia calls him out for his sort of honeyed words. She says, “You always know the right thing to say.” And I don’t think she means it as a compliment. Do you?

Mark Bonnar: No, he has that in him, that kind of apparent coolness towards extreme situations. But that’s why he’s where he is. That’s how he’s got to where he is. As he says in that speech, “If you, if you develop that kind of courage, then you’ll get through this too.” It’s not a callousness, it’s a necessity.

Jace Lacob: You’re referencing what I call the chicken dinner scene where things come to a head for the three of them. And he does reveal in that moment, how he can be so matter of fact about war.

CLIP

Sir James: Every day in the trenches we walked past the body of a fellow officer, a friend. His face had been blown off by a shell. We had no means of burying him. We didn’t even cover him. We walked past him every day, and we looked the other way. Now, you might think that callous, but really it was a kind of courage—an acceptance of our lot. The horror was, and could not be denied. We knew at any moment that faceless body could be one of us. We saw, but we did not look.

Jace Lacob: And I think that is the underpinning of this entire facade of coolness for him, what he’s concealing, this gallows humor, this debonair thing, is this sense of trauma. Did this feel like a momentous moment for this character to summon the specter of truth and hold it out for these two women to see and to look at?

Mark Bonnar: Well, yes, I think so. And I think it’s an important speech because there was a generation of men in both wars who were walking wounded, but not physically. And to go back to my own family, my dad said he would often hear his dad screaming at night with night terrors. I don’t know if he knew that’s what it was at the time but, Sir James’s experience was almost universal for his generation of men, but also for Harry Chase’s generation of men. They were walking wounded and they had seen more than you should ever see as a young man, and been through terrible, terrible things.

So I think it’s a very, very important speech. Not just for Sir James, because he obviously on the outside is charm personified and full of bon viveur, but, for all of the men and women of course, who saw combat, or so not just saw combat, but saw dreadful things. Civilians too. It wasn’t just men fighting in the front. It was everyone, everyone. It was a generation of traumatized people, of people with PTSD. So I think, yes, that particular speech brings all that into sharp contrast.

Jace Lacob: Episode five is directed by the aforementioned Meenu Gaur, who also directed you in BBC’s upcoming Agatha Christie adaptation murders. How would you describe Meenu as a director?

Mark Bonnar: Well, she’s fantastic, first of all. She’s a very kind of relaxed presence, which is always, always good. She’s very relaxed. She’s very approachable. She’s got great ideas, great notes, and she likes a laugh. And you know, it’s a strange job, but the most important thing, one of the most important things I think about it, is to retain a sense of play. Otherwise, you’re not going to have that sharp sense of the ridiculous if you don’t. So yes, Meenu is a great enabler and a lovely person to have around.

Jace Lacob: Mark Bonnar, thank you so very much.

Mark Bonnar: You’re welcome. Thanks, Jace.

And we’re back with World on Fire historical advisor Richard Overy to unpack some historical topics from Episode Five.

Jace Lacob: A major battle site in this episode is a water distillery in the North African desert. What was the primary source of water for distilleries such as these? Was there a reliance even on ancient Roman aqueducts as a freshwater source?

Richard Overy: Well, freshwater was at a premium, and it was expensive to transport when you wanted to transport other things, like ammunition or armaments and so on. And so, yes, they made use of anything they could find where freshwater was a possibility. Arabs, of course, knew where you could get fresh water and they would use oases and so on to refurbish their supplies. But for the warring armies on both sides, it was difficult to guarantee that you could find an earthbound source of freshwater.

So yes, you made use of whatever you could. And on both sides, or certainly the German and Italian side, of course, if they had to retreat, would destroy or poison fresh water sources to make it even more difficult for the advancing army to find it.

Jace Lacob: Given the desert setting, yes, you would imagine that water would be a highly precious resource, that it would be sabotaged upon retreating. How much of the conflict of the Western Desert Campaign then was sort of over water?

Richard Overy: Well, I mean, you wouldn’t actually target water specifically, but water was something at the front of every general’s mind when he was thinking about, what do my forces need, and what will happen if the water runs out? And so from that point of view, it was a very important part of their forward planning on both sides, German, Italian, and British.

And the British had advantages, they came increasingly to dominate the eastern Mediterranean in naval terms. And they could regularly supply, through Egypt, fresh water for their forces. But once their forces were engaged in combat, it was often difficult to get it forward where it was actually needed.

So what you see in World on Fire, people are desperately thirsty. Rationing it out to just a little bit, to last you for the whole day was for many soldiers, a reality. It didn’t go forever, but it could go on for weeks.

Jace Lacob: In this episode, Kasia does catch the Polish drafters sending blueprints back to Germany, a clear act of espionage. MI5 hopes to turn her to send information back and this seems to be maybe a strategy of the security service, the flipping of foreign operatives as part of the double cross system. So I’m wondering how inept German Spies actually were in Britain?

Richard Overy: Well, they were pretty inept. I mean, they often arrived without even proper maps, some of them couldn’t speak English properly. And they would make all kinds of mistakes the first time they spoke to anybody, or went into a shop. Their radio equipment was very easy for the British to intercept and monitor.

Having said that, they did turn some of them. And some of the ones that they turned were extremely important double agents. They became, if you like, more competent once they were working for MI5 than they were when they were working for the Abwehr, the German counterintelligence.

So we shouldn’t dismiss them entirely. Also, I think in some cases, of course, the spies wanted to change sides. They didn’t want to be on the German side and were quite happy to take part in the double cross system. People who were spying had a range of motives. So yes, inept so they were all caught, but having been caught, some of them played a very important part actually in the British war effort.

Jace Lacob: How successful was the security service at identifying and catching them if they were showing up with bad maps or being unable to speak English? Was it an advantage of the security service or was it due to just sort of that ineptness or was it just both?

Richard Overy: Well, both. I mean, MI5 was pretty good at what it did. Security services were in most places, of course, by the Second World War. And that was what their job was, of course, in 1940 and 1941, was to look for 5th columnists, to look for spies, and they relied a great deal again, on the public providing them with information about possible suspects. In that case, they had to waste, again, like the Gestapo, quite a lot of time chasing dead ends, as it turned out. So it’s a combination, if you like. MI5 is on the watch, and the Germans are not very good at avoiding them.

Jace Lacob: Harry Chase ends up shooting a German prisoner in this episode after he’s goaded into killing him. Would this have been considered murder or a breach of the Geneva Convention of 1929?

Richard Overy: That’s a good question actually. You can see in this particular case in World on Fire that he’s pushed to a limit and I think many British soldiers in the Second World War pushed to that limit would have done that too, would’ve not thought much about it actually. I mean he agonizes a bit more, I think, than most people. It has to be said that although on the whole the British Army respected the Geneva Convention there are plenty of examples when they didn’t. So I think that shouldn’t surprise us.

If he’d been caught in the act and, or he’d been handed over to a senior officer, it’s difficult to know how he would have been treated. He would not automatically have been court martialed and accused of a war crime. And on the other side, on the German side too, that would not have been perhaps an automatic. But it doesn’t happen. He gets off.

But it’s an acute moment which I think captures the way in which many soldiers in the Second World War must have thought about their enemy. But having said that, the British and the Americans were supposed to respect the Geneva Convention, and so the Germans in the west respected the Geneva Convention as well, violating it occasionally as the British did.

Jace Lacob: Richard Overy, thank you so very much.

Richard Overy: My pleasure.

Next time, Henriette sends David off on the last leg of his escape route back to England.

CLIP

Henriette: It is time.

David: Are you sure?

Henriette: One flashlight, I saw. We don’t have long.

David: No.

Will David make it home? Be sure to tune in to the series finale of World on Fire this Sunday, November 19th to find out.