This script has been lightly edited for clarity

Jace Lacob: I’m Jace Lacob, and you’re listening to MASTERPIECE Studio.

The brutality of life in the North African desert continues to weigh upon the British and Allied troops, as they contend with scorching sun, sandstorms, and enemy fire. As the Germans close in on their location, the men pack up and head for Tobruk. Harry is sent to Cairo with a leg infection, and Stan is left with no choice but to hitch a ride with the Sapper unit.

CLIP

Stan: Sir, wait! Sir!

Rajib: Come on, come on. Looks like we’re your last ride out of here. Come and join a real regiment. Come on.

Stan: Go to hell.

Rajib: Welcome to the British Indian Army.

In Manchester, Kasia discovers that Robina’s house guest, Sir James, is not quite who he says he is. After rifling through his things, Kasia discovers that Sir James is an undercover MI5 agent on a special mission. And he just might be her ticket out of domestic life at Chase manor.

CLIP

Sir James: Kasia, I’m not making any promises, but I may be able to help you.

Kasia: To get back to Warsaw?

Sir James: No, I can’t do that.

Kasia: Then you’re wasting my time.

Sir James: I hear you have nightmares?

Kasia: What has that got to do with you?

Sir James: I know you’re not in tip top shape mentally, yet I’m risking offering you something. The least you can do is listen to what it is before discounting it out of hand.

Back in a North African desert field hospital, Harry is on the mend. And as chance would have it, Lois is stationed at this very same hospital. They each take comfort in seeing a familiar face, but the war has taken a toll on both of them, each in different ways.

CLIP

Harry: What are you doing in Egypt?

Lois: I could ask you the same thing.

Harry: I was on a mission, I was injured.

Lois: Me too. It’s how I ended up here.

Harry: I don’t understand.

Lois: Vera’s fine by the way. She’s with your mother, and Kasia.

Harry: I still don’t understand why you’re here.

This week, director Meenu Gaur joins us to discuss how she balanced the big, dramatic moments of battle with the small, tender moments of love, longing, and domesticity.

Jace Lacob: This week we are joined by World on Fire director, Meenu Gaur. Welcome.

Meenu Gaur: Hello. Thank you so much for having me.

Jace Lacob: Thanks for talking with us. In your career, you seem to relish the opportunity to switch between genres showing an affinity for tackling such diverse styles as feminist Noir or Bollywood style dramas. What attracted you to directing an episode of World on Fire in particular?

Meenu Gaur: When I got the script, the first thing that struck me, and I had already seen season one so I was aware that this was not your typical World War II drama in as much that it wasn’t just like a patriotic piece about one country versus another, I think it was so much more a human drama in trying to tell stories about just everyday normal people in their everyday lives and how the war impacted those lives. And I think that’s rare in the telling of World War II stories. So, if there was ever going to be a war story that I would love to tell, it would be this.

And the fact that Pete, who’s the creator of the show, has this way of really empathetically bringing very nuanced ways of looking into masculinity and the stories of women. So, there’s this whole aspect of a gendered way of looking at the war and how both men and women were impacted by it. So, all of that really just drew me in. I think there are aspects to this writing that are very beautiful and rare when we access World War II stories.

Jace Lacob: It’s interesting you say that because, as you say, World on Fire might also be about those sort of big moments. There are, in the first episode you direct, certainly explosions and attacks, but it does also capture those small, quiet moments of futility or despair or even domesticity. How do you then approach directing a series that veers so wildly between extremes like that?

Meenu Gaur: I think that’s a really good point you make, that there are those big moments of the battles and of the combat, and then there are really tender moments which are just about two individuals’ love or longing or desire or fragility, fear, whatever, all of that, in those very difficult times that people were living through.

And in this, there are multiple storylines taking place in multiple countries like Germany, France, and then we are in Manchester, but then we are in the North African desert where the war is taking place. So, you’re kind of moving between different storylines. I think one of the biggest challenges in directing this piece was always about making sure that one is able to go through that arc of every character’s journey across these different episodes. And I think that’s always actually more difficult in some ways than doing the big war combat moments.

I think it’s always more challenging to keep a track on the human story, on the emotion of that individual character and their journey. And to never lose thread of that when very, very spectacular things are happening on screen. Of course, it’s the actors who were also in Season One, they sort of carried that burden very well of their individual character journeys and arcs.

Jace Lacob: You yourself, as you said, were a fan of series one of World on Fire when it went out in the UK in 2019. Since then, there’s been a global pandemic, war in Ukraine, upheaval around the world. How would you describe the experience of stepping into the director’s chair to helm a project that feels particularly timely after these events?

Meenu Gaur: Yeah, I think there’s a great responsibility when we tell war stories, and that becomes even greater in a time such as this. And that is why the way that the writer and creator Pete approaches it, is so beautiful because I think he’s always aware of being able to bring in the voice that is most marginal, into the center while telling the story. And that’s in series one as well.

The very stories that he chooses to tell are not stories that you would necessarily think about, or themes that you would think about when you think about World War II. The fact that Series 1 opens with the war in Poland, not that much spoken about that aspect of World War II, not that much spoken about country when we think about World War II.

So, I think that responsibility of knowing that there are smaller stories that get submerged in larger narratives. And I think what’s important is that when we do tell war stories, we are able to excavate those stories that sort of get erased in the larger narratives to tell those smaller stories, because that is where the sort of human element of war is. And not to lose track of that, that the real repercussions of war are on people, right? They’re not on countries or more abstract things. They are about individual people and the cost that that war and that violence has on individual lives.

Jace Lacob: You mentioned the concept of erasure. There have been no shortage of films and television projects that have told the story of World War II. But roughly two and a half million South Asians served in the British Indian Army in World War II. Why are we only now seeing their stories on screen in an English language project?

Meenu Gaur: That is shocking, isn’t it? And it’s not just World War II, it’s World War I as well. The number of people from South Asia and in fact other countries in other parts of Asia and Africa, who would have served in these wars and the number of them who would have never returned home again, is huge, huge. And, that it doesn’t form part of mainstream storytelling, think about all of your favorite World War II films and I would be very surprised that even if like 1 percent or 2 percent of them had any visual representation of people from these countries who served the war, whether it was World War I or II.

So that is a definite and clear erasure. And one of the things that I was obviously very, very moved by was the story of the officer in the Indian Army in Season Two. And I hope that this is now going to be opening up to that narrative, to that, because it’s a very poignant part of history, because these were people who came to very faraway lands to very, very different climates and in very hard conditions very far away from home and fought these wars. Their contribution to the war is completely, not far from being celebrated, it’s completely erased.

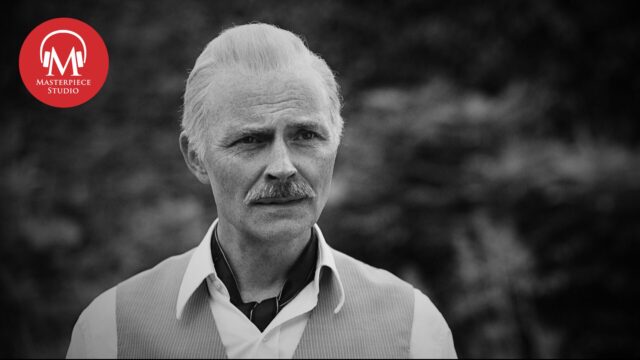

Jace Lacob: The character you’re referencing, of course, is Rajib, played masterfully by Ahad Raza Mir, this season, to me, one of the biggest breakout characters of the show as a whole. What do you feel Rajib brings to the narrative of World on Fire?

Meenu Gaur: I think Rajib is a very, very wonderfully nuanced character because he’s a real hero. He’s a real war hero in the sense that he takes his duty as a soldier extremely seriously. And yet, where he comes from, India, an undivided India, he is at that very moment in history, actually waging a fight for independence from the colonial forces. So, he’s fighting for the British Empire at a time when back home, there’s a very, very different fight happening.

And so that conflict is a very wonderfully sort of written conflict for the character. And I think it’s Rajib’s sort of dilemma and him realizing just what we were talking about, the erasure in a sense, in a very individual way, realizing that despite his men and him so heroically fighting this war, in a sense, they do not have the same stature, respect, that other soldiers have in the army. And that sort of understanding and how that understanding sort of shakes his entire belief in what he’s doing in the moment.

Jace Lacob: It’s especially heartbreaking, I think, to watch Rajib’s trajectory this season, knowing that he believes in fighting for Britain, he’s fighting for India. I think it’s just beautifully done.

I want to take a little bit of a step back. You occupy a very unique place in cinema. Perhaps we could say you’re sitting in the director’s chair at a crossroads between Pakistan, India, and Britain. And there’s an affinity for Pakistani drama in India and Bollywood excess in Pakistan, but a lot of these projects are banned on either side of the border. How do you so deftly navigate those cultural schisms?

Meenu Gaur: I’m not sure I do it deftly, for starters. I think the obstacles are very real for all artists trying to work with each other, work across industries, tell stories that encompass both worlds, I think. Anybody who wants to or tries to do that, there will always be difficulties and obstacles. But at the same time, there are a huge number of artists and musicians and filmmakers who are doing that.

And I’ve had associations with producers and executives who have endeavored to tell these stories. So, for instance one of my last series that I did, which was a feminist Noir, was such a project and it was with this producer who repeatedly tries to do these stories which are across India and Pakistan and international industries.

So, yeah, that’s it. I’ve been lucky to find colleagues and associates who are helming projects like that and join and collaborate with them.

Jace Lacob: Noir was of course an outgrowth of the cynicism that followed in the wake of World War II. Do you think it’s perhaps logical then as a director to search out a project that allows you to recreate the very conditions that led to Noir?

Meenu Gaur: Yeah, that’s a very, very good point. I didn’t see it as the logical next step from Noir actually, to take a step back and do a World War II drama, but that’s a good point. That’s all I can say. But, the whole project to do a Feminist Noir and Desi Noir was just that I find it surprising with Noir being one of my favorite genres, but I also find it very annoying and irritating that it has such a sort of strong male gaze in as much as you only can encounter the character of the femme fatale, which most Noirs have, through the male character, and their voiceover.

So, I was kind of just endeavoring to turn Noir on its head and see what it would be like to do it from the perspective of the Femme Fatale and what it would do to the morality of the story. And of course, what it would do is it totally makes the story about the Femme Fatale and then it changes everything, doesn’t it?

So, I think what’s similar to World on Fire is about what I previously said about choosing a marginal approach to stories that have been told before. It’s just about shifting your position and seeing it from another place. And I think World on Fire does that. It just shifts the way we have looked at these stories and sees it from down below there, not countries and nations and battles and events, but just down there with people and by just doing that, it changes the way that we perceive World War II stories.

MIDROLL

Jace Lacob: Episode three, your first directed episode this season, begins in Libya. There are fast cuts. There’s a lot of action. Harry falls over, wounded and in need of hospital. The camera shakes with the reverberation of missiles and we cut to a castle in Brandenburg, Germany, and it’s calm and lush. And these German girls go through their synchronized exercise regimen. What were you looking to say with this juxtaposition of images?

Meenu Gaur: The best way I can put it, there is a ‘meanwhile’ in World War II stories, because war is taking place across space and time, isn’t it? The fact that World on Fire always takes you somewhere else as well that you may not think of North Africa for instance, right? Or as you said, the story about the Indian sappers, et cetera. So, I think that that juxtaposition is about that element of ‘meanwhile’ in another sort of time and space, right? And I think that kind of cutting is there across this episode and even the other episode that I directed, because that’s kind of the structure of the storytelling.

Jace Lacob: I love that though, ‘meanwhile’. There is a sort of balletic energy to the scene of the Lebensborn girls, the closest this season comes to a full musical number, if you will. Did you relish the opportunity to direct this sequence?

Meenu Gaur: Yes. Originally, if I remember correctly, I think maybe there wasn’t that element on the lawns. But I had been watching some archival videos of these girls and I don’t recall the exact words, but it was about how there was this great investment in beauty and health for these women, these young women, and there’s gymnastics and very, very sort of beautiful dance and gymnastics regime that all of these girls were involved in.

And when you saw those videos, the form of it was quite hypnotic to watch. And I think what was important is that it’s important that when you tell a story, you try to tell it from the point of view and the morality of whose story it is. Because what I’m trying to say here, is that there is a character who’s obviously drawn to this, is being seduced by this, and therefore, we have to see that seduction and we have to see what that attraction is. Because if we don’t see it from her point of view, then we never understand her story, right? So, I think it was an attempt to see it from this character Marga’s lens, really.

Jace Lacob: I love it. You shot the early domestic scenes at the Chase household through doorways, lending these scenes the feel of a roman à clef. Was this an intentional shot composition adding to the sense of claustrophobia that these very unlikely housemates are feeling?

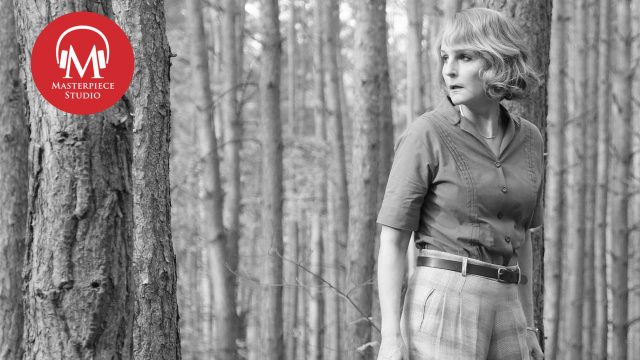

Meenu Gaur: Yes, yes, exactly that, really. The women characters have this sense of being trapped in each one of their situations. So, one of the characters is trapped because she’d much rather fight. From season one, she has all this trauma and anger, and she wants to fight, but she’s placed into this domestic situation.

CLIP

Kasia: I fought in the resistance in Warsaw. I belong there where I can make a difference. Get me home.

Sir James: I’m afraid that’s not in my gift.

Kasia: I belong in Poland.

Sir James: It’s out of the question.

Meenu Gaur: The other woman, she’s a new mother and she’s grappling with her losses, which are huge.

CLIP

Lois: I’m not saying I’m not feeling lost. But I am fighting back. And this, me being here, that is part of me fighting back.

Harry: I’m so sorry. You must’ve felt so lonely.

Meenu Gaur: And the mother, the matriarch in this entire situation is just having to deal with all this mess, which is not her creation. And she’s being pushed into situations which make her very, very uncomfortable.

CLIP

(Vera crying)

Robina: Vera please, don’t be so stubborn. It’s a trait of your mother’s and I really wish you wouldn’t indulge!

Sir James: I don’t know much about babies, but logical reasoning might work, I suppose.

Robina: I’m past caring to be honest.

Sir James: Are you having a sherry?

Robina: No, it’s a little late for me. Thank you.

Meenu Gaur: So, I was trying to get that energy of what these characters are feeling and use, as you said, doorways, windows, but also shadows. There are these sorts of grills on the windows, and they throw these sort of grilled shadows on people, and that literally looks like a prison when you look at it. So exactly what you said was what I was attempting to do.

Jace Lacob: The examination scene feels straight out of a body horror film. It’s full of, and again, we’re going to use that word shadows, but also menace, surgical instruments, eerie angles. How did you approach these scenes with Marga, with her naivete and stark contrast to these rather ominous surroundings?

Meenu Gaur: I think when I first read the story of Marga, again I was very, very intrigued by how we had approached…you see, one is used to stories about how the bodies of women become a site in times of war, right? We have read about that. We know about that aspect. But this was such a different story, telling you about how women and their bodies get used in war, but from a very different perspective.

So, what I was trying to do is that I realized that this story was about a young girl, I wanted to present a very embodied reality and use that element of which what she’s been put through, to tell her story, to feel that aspect of…see it from Marga’s point of view, everything from her point of view, and feel it as much as possible. And the only word I can really use is embodied. So, there’s a lot of her hands and there’s a lot of her eyes and different aspects. There’s also the use of her breath in many places. So just to be with her point of view as much as possible. That’s what I was attempting.

And therefore, when there is that moment of vulnerability and extreme trauma, then what happens is disembodied, if that makes sense to you. So, to see it through the lens of embodied and disembodied and create a language through that. That’s what I was attempting to do. And it rests on the work of many, many, many, many other wonderful women artists and filmmakers who have thought through all of this. And I was accessing all that.

Jace Lacob: The British Indian army finds itself under intense fire. There’s a lot of sand, the scene is washed with yellows, the truck blows up. Those yellows are then contrasted with the blue that saturates the scenes in Romanville Prison. How do you approach the use of color as a director? Is it something that you consciously use?

Meenu Gaur: Yeah, color palettes are very, very important for me. And especially in World on Fire, where you’re very quickly moving between worlds, right? So, you have to contrast these worlds. And one of the ways that you do it is through the color palette. So, I kind of tried to lean into whatever the writer has already put in. I think there are little codes there that you can get into. And then from there, unpack what the intention is really, what the world is supposed to look like. And that’s how I approach it.

Jace Lacob: The final scene in the desert is the most intense of this entire episode, and some might argue of the entire season. Rajib, Stan, and Bruno collapse at the edge of an Allied camp, and the white men rush to Stan and Bruno rather than to Rajib.

CLIP

Stan: Him. Help him. He is a British officer. You’re supposed to go to him! You go to him! You’re supposed to go to him! You go to him!

Jace Lacob: As a South Asian director yourself, what was it like helming this sequence, one that so painfully, brutally depicts the institutionalized racism at play here?

Meenu Gaur: It still moves me as you’re even talking about it. What is lovely about the scene is that you see an individual’s heart break. That is the most poignant way to tell such a big story of, as you said, institutionalized racism, that the only way to tell it is seeing one human being’s heart break. And that’s what I saw in that moment.

This is a person who desperately hangs on to an idea or a view of the world, when he says in another scene, he says this line that the value of a life is the value of a life is the value of a life. And what he’s really saying through that line is that everybody is equal, and nobody’s life is less than the others.

And it’s this sort of almost desperate belief he has about the goodness and the equality and all the great values that he fights for, we fight for as human beings. And in that one moment, when I say you see his heart break, he knows that it’s not true. The value of a life is not the value of a life. Not the value. And in fact, despite the fact that Bruno is an enemy, the natural thing would be for his side to go to him, to the enemy and save him rather than the officer from the British Indian Army.

Jace Lacob: You grew up watching movies with your parents, sometimes three or four a night. Your mother, I believe, was an ardent fan of horror and arthouse cinema. Did you inherit those tastes from her?

Meenu Gaur: My mother is a proper cinephile in the sense that she sort of not only consumes cinema, but she consumes the whole universe, if you know what I mean? Like, the fandom and if you want to know trivia, she’d know it, about the making of the film and the actors and everything. So, yeah, I think I sort of grew up with all of that excitement about cinema and I love horror and it’s definitely what I want to be doing very soon.

Jace Lacob: You did a war project. You did a Christie. You’re looking to do horror. What is next for you?

Meenu Gaur: I already told you that there’s something about wanting to do stories or genres that have been done across decades but bringing to it something different, bringing to it a lens or a way of seeing it that hasn’t been done before. So that’s my larger project. And I try to do that with whatever is presented to me. I always try to think about, how can I infuse this with a voice or do a telling of this that we haven’t quite seen before? So it’s familiar, but it’s also bringing in a new perspective, which is what I’d like to do with whatever comes up next, really, even if it’s horror.

Jace Lacob: Well, I can’t wait to see what’s next. Meenu Gaur, thank you so very much.

Meenu Gaur: Thank you so much. It’s been lovely chatting.

And we’re back with World on Fire historical advisor Richard Overy to unpack some historical topics from Episodes Two and Three.

Jace Lacob: Marga informs on Gertha, betraying her best friend. While it’s since become a trope in films and television programs about fascism, how common an occurrence was naming names? Was selling someone out sometimes the only way to save your own skin?

Richard Overy: It was, I’m afraid. Denunciation, telling on your neighbors, reporting to the authorities was much more widespread, I think, than we might have expected. And what happens in World on Fire is not surprising. Marga wants to protect herself. She wants to protect her parents. She wants to do what she wants to do. And the problem is her friend is too young and too naive to understand the risks she’s running.

Jace Lacob: Sir James turns up at Robina Chase’s rather lovely estate. Were military personnel often billeted at country homes around England during the war? And was it considered an obligation during wartime to have officers or even soldiers billeted in your home, even for the upper class?

Richard Overy: Yes. I mean, it was widespread. Quite comfortable country homes were taken over and a wing would be left to the family to live in until the war was over. I think in World on Fire, it’s unusual, I think, to have an MI5 officer stationed, a senior MI5 officer, stationed in an ordinary house. In fact, it’s one of those things in World on Fire, which I think is just on the edge of what’s possible. But otherwise, yes, where it was needed. Not every house, of course, was requisitioned, but where it was needed, yes. It was an obligation. You couldn’t say no.

Jace Lacob: The British army is beset by a series of sandstorms in the desert. One member of the squad heads out with some bog roll or toilet paper and ends up dying in the sand, essentially drowning. While war is dangerous, was this a common way to die for the British army fighting in North Africa?

Richard Overy: Well, not a common way, no, but it happened. That is based on memoirs and records from the war in North Africa. You had to be very careful in the sandstorm. I mean, yet another evidence that this is a dangerous and unpredictable environment in which to be fighting. If that didn’t get you, something else might get you. Scorpions, for example, which were widespread, snakes. I mean, most soldiers did survive with a generally high level of discomfort. But yes, accidents like this happened all the time.

Jace Lacob: What was the role of the British Indian Army in terms of the war effort, a la the sappers that we see here and what sort of role did they play, and was anyone in Britain even aware of their existence?

Richard Overy: Well, they were aware, but it has to be said that the British were quite ruthless in recruiting non-British manpower to fight their battles. By 1941, only a quarter of the troops in North Africa were British. Indians, Australians, later New Zealanders, later Poles as well, were all recruited into the battleground. They’d fought there before in the First World War too, so there was a kind of continuity, if you like, between the two conflicts. But the Indian Army became the largest volunteer army in the war, two million Indians volunteering to fight for Britain.

But as you see in World on Fire, they fight for Britain, but they’re also fighting for India. There’s a strong sense among many of the rank-and-file Indian soldiers during the war, yes they would fight Britain’s war, but they wanted to be repaid at the end with Indian independence. And that comes through quite strongly, I think, in the drama.

Jace Lacob: It does. Given how widespread that was then, how many South Asians actually did participate in both World Wars, why do you feel the contributions of South Asians have been largely ignored or deliberately forgotten from history books and or film or television portrayals of World War II specifically?

Richard Overy: Well, there’s a lot more written about it now. Historians have done a lot in the last 25 years in highlighting the contribution of the wider empire. And so, if you’re a second world war enthusiast, you will have read something now about this. But for a long time, it wasn’t important to the British narrative. What was important was the Battle of Britain, the Blitz, surviving, then D Day; the things that you could identify clearly with Britain rather than with the wider empire.

And that kind of amnesia has dominated the memory of the war in the last 80 years, and it shouldn’t because the British were heavily reliant on troops from other countries, not British troops. They were heavily reliant on Indians, New Zealanders, Canadians, South Africans, Australians, and it’s a contribution which has to be built in. I think when we talk now about the British war effort, we really need to start talking always about the British Empire war effort. That’s what it was.

Jace Lacob: Lois joins the Auxiliary Territorial Service, or ATS, the women’s branch of the British Army. What was the role of the ATS during the war, and what sort of duties did its members perform beyond just clerking?

Richard Overy: Well, it did all the kinds of things it could do except combat. They did secretarial work, they did radio work, they could work with radar. Some of them were posted to Bletchley Park to the code and cipher school engaged with intelligence work. They drove ambulances, a wide range of activities that freed men for doing other things.

Jace Lacob: Marga is examined by a Lebensborn doctor in this episode who appears to be using Phrenology as a way of deciding whether she’s worthy to serve as a broodmare. Was there a Nazi belief in Phonology and other pseudosciences?

Richard Overy: Well, there was, yes. They constructed the most elaborate means to try and work out somebody’s racial categorization. And they had forms which were then filled out. And if you look at them, they’re quite bizarre. It’s got all kinds of things about shape of the head, length of the nose, width of the brow, etc., color of the hair. Because they were persuaded that you could use all these kinds of measurements to work out somebody’s racial value.

And actually, there were lists that they compiled on their race cards as they were called. They would have a list. One list would have all the characteristics we think of as Aryan man. And the last list would have all the characteristics you would think of as the Nazi stereotypical Jew. So, it served a particular purpose.

Jace Lacob: Richard Overy, thank you so very much.

Richard Overy: My pleasure.

Next time, the British Army makes it to Tobruk, but the internal tension continues to grow.

CLIP

Captain Briggs: Pal, your men will lay a tactical minefield in order to draw in the tags for artillery to strike.

Rajib: Sir if I may. The enemy is already familiar with the tank trap. Standard defense formation might be more advisable.

Captain Briggs: Thank you Pal. You will lay a tactical minefield as per orders.

Rajib: Sir.

Next week, don’t miss actor Ahad Raza Mir, who plays the fearless and compassionate second lieutenant leading the British Indian Army’s sapper unit.