Surprising History in Sanditon Season 3

Discover intriguing details about the true history covered in Sanditon Season 3, from dangerous parlor games to self-indulgent royalty. Each Sanditon episode includes surprising bits of the Regency era’s past—get your topical history questions answered here!

- 1.

Episode 1 | Snapdragon: An Extreme Regency Parlor Game

A mother presides over the Snapdragon bowl. This season in Episode 1 we saw the Parkers host an evening game of Snapdragon. This competition was a popular Regency entertainment that had both adults and children snatching buoyant raisins out of a dish of burning brandy. The game involved pouring brandy into a large shallow bowl, tossing in raisins, and setting the alcohol ablaze. (Best played in the dark, of course!) At 50 percent alcohol, the burning brandy wasn’t hot enough to turn the raisins—or snapdragons—into ash, and they could be plucked by hand out of the ghostly blue flames and popped into one’s mouth. Snapdragon was rousing, scary, and relied on speed. The intrepid soul taking the most snapdragons was said to meet their true love that year.

- 2.

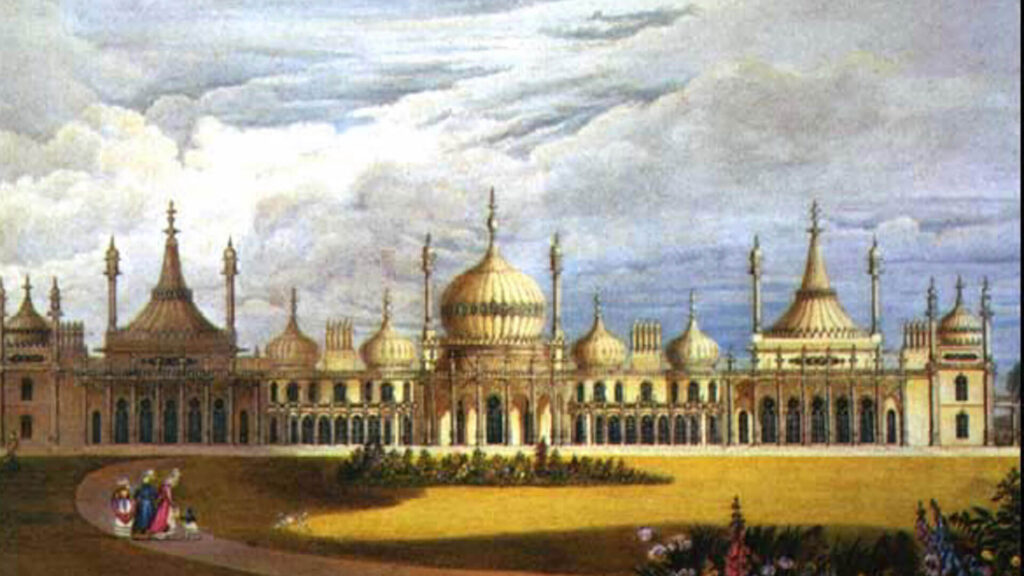

Episode 1 | George IV: from Prince Regent to King

View of the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. In Episode 1, Lady Montrose pointedly queries Lady Susan (rumored to be the royal’s mistress) on whether the “newly crowned king” will visit Sanditon. Who was this king and would he really leave London for the coast?

King George IV was England’s former Prince Regent. The Regency era spans 1811 to 1820; years when George III was no longer mentally fit to rule. The new monarch George IV adored resort society—one of his most self-indulgent projects was the outlandish Royal Pavilion built in the seaside town of Brighton. Fascinated by the distant orient, George overspent recklessly on imported Chinese furniture, decorative arts, and hand-painted wallpaper for this vacation palace. Racking up spectacular debt wasn’t out of character, as he was extravagant in most things, from food and drink to womanizing. Overweight and oversexed, George IV ultimately ruined his own reputation and was unpopular with his subjects.

- 3.

Episode 1 | Every New Resort Had an “Old Town”

Bognor Regis resort in West Sussex saw rapid growth in the mid-1800s. In Episode 1, we’re introduced to a far less glamorous side of Sanditon—its original Old Town. Budding resorts at first provided locals (fishermen or village shop owners) with lucrative construction work or the opportunity to expand their small business. In the earliest days, entrepreneurial residents even rented out a spare room in their cottage. But as is too often the case, a developer’s appetite to host growing numbers of well-off vacationers meant crowding out or razing the older part of town to build modern facilities. In just a handful of years during the Regency era, a quiet fishing village could transform into a sophisticated hot spot boasting numerous amenities.

- 4.

Episode 2 | America's 1st Black Opera Star

Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, dubbed 'The Black Swan' Episode 2 has Arthur Parker inviting “the celebrated American soprano, Miss Elizabeth Greenhorn” to perform for the king’s visit. In fact, there was a popular Black opera soloist who traveled to England and sang for Queen Victoria—about 30 years after Sanditon is set. Her name was Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, (not Greenhorn), and her command of “white” music like arias and ballads challenged preexisting ideas about artistry and race.

Greenfield was born into slavery in Mississippi around 1820 but secured freedom and education in Philadelphia. Her powerful voice and astonishing range opened doors to a musical career in the 1850s. While most Black performers in antebellum America were limited to minstrel shows, Greenfield famously toured the northeast singing opera. (Black audiences were not allowed in her prestigious concert venues.) Journalists dubbed Greenfield “the Black Swan,” but many also struggled to reconcile her talents with their bigotry. She later toured Europe along with friend Harriet Beecher Stowe. Singing for the queen at Buckingham Palace in 1854, Greenfield was the first African American vocalist to give a command performance for British royalty.

- 5.

Episode 3 | Etiquette of a Regency Shooting Party

In Episode 3, Alexander Colbourne hosts a shooting party on his estate. Shooting grouse and pheasant, hunting larger game, and fishing lured many gentlemen to the countryside. Such upper-class activities were almost compulsory during certain seasons. By law, participants either had to own a certain acreage of land themselves or be invited to hunt there. Putting game on one’s dinner table was thus a status symbol. (Penalties for poachers ranged from a fine or prison time to deportation and even hanging, though laws relaxed a decade later, allowing those with a permit to hunt game birds and rabbits.)

While birding, gentry dressed the part in top hats, double-breasted shooting jackets, and laced or buckled gaiters over their breeches. They walked the land cradling “scatterguns,” which now and then misfired—or just plain exploded. Dogs might flush the birds, or men dubbed “beaters” would drive game toward a line of hunters. All the shot birds were collected and shared amongst guests. To this day, the August opening of England’s four-month grouse season is known as “the Glorious Twelfth.”

- 6.

Episode 4 | Gay Subculture in 19th Century England

Arthur Parker tells Harry Montrose in E4 that he also prefers “grouse to pheasant,” but worries what his family will think. Harry responds that the Parkers “might not be as surprised as you would suspect.”

In early 19th century Britain, same sex relationships were something of an open secret. People knew homosexuality existed, though publicly discussing it was taboo. Societal opinion ranged from outright homophobia to curiosity and indifference. The laws were more grievous: Up until 1861, sexual intercourse between men was punishable by death. (Lesbianism was not explicitly targeted by any legislation.) Yet Regency England still offered opportunities for a gay male subculture. “Molly houses” were a welcome refuge for men who today might identify as gay, bisexual, or queer; they gathered for drinks and smoking, gossip, dance, drag entertainment, and flirtation. These watering holes were constantly in danger of being raided however, with patrons hauled to prison to await hearings. Such raids forced molly houses deeper underground. While the subculture did not dwindle during the Regency era, the number of supporting establishments did.

- 7.

Episode 4 | Fireworks: Not a Novelty

1749 firework display held by the Duke of Richmond near the Thames in Whitehall, London In Episode 4, Georgiana’s celebration party featured flame throwers and fireworks. Turns out, these were hardly a novelty in Jane Austen’s day. Fireworks originated in ancient China and went through centuries of development—their first recorded use in England was Henry VII’s 1486 wedding. By Britain’s Regency years, fireworks included colors beyond orange, and displays set to music were common entertainments in public gardens where people gathered to enjoy an evening outdoors. Fireworks were, in fact, so popular that the career of pyrotechnician became a thing. These brave souls were sometimes called green men as they covered their heads and shoulders with fresh leaves to protect against sparks.

- 8.

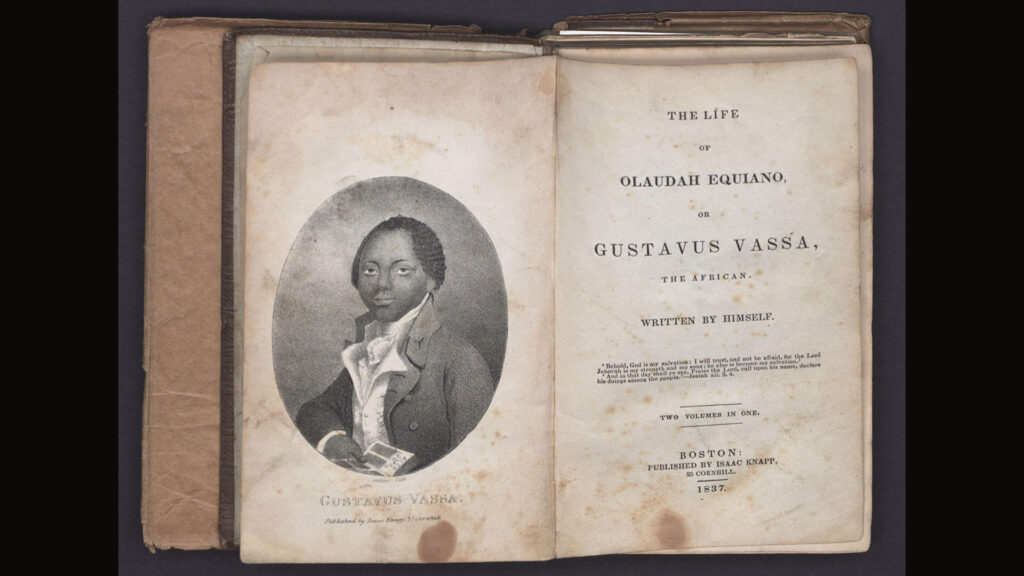

Episode 5 | Sons of Africa

Book titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, written by a prominent Sons of Africa member. In Episode 5, Georgiana learns it was Otis Molyneaux’s work with the Sons of Africa that led to finding her mother. Sons of Africa, founded in 1787, was a community of Africans who had been freed from slavery and were living in London. It is considered Britain’s first Black political organization and its abolitionist work into the early 1800s is often overshadowed by that of its white allies. Sons of Africa members enlightened the British public about the realities of slavery. They lectured publicly, petitioned Parliament, wrote to newspapers to spark debate, and published memoirs sharing their lived, first-hand experiences of slavery’s terrifying reality. Their collective voice was a powerful force in the protracted fight to change both British law and public opinion. England finally abolished slavery in 1833.

- 9.

Episode 6 | “Bestowing a Living”

In Episode 6, Lady Denham finally grants “a living” to Edward. Flabbergasted, he understands her to mean a living as clergyman. It turns out that during the Regency era, local church leaders were not necessarily ordained but could be appointed when a rich patron purchased the position for them. These installed rectors received a portion of parish tithes to support themselves; they served the church but also had local administrative duties like registering births, marriages, and deaths. Once situated in a living, one only lost the position for the most serious of disciplinary grounds. We have to wonder just how long Edward Denham will last in his new calling!

- 10.

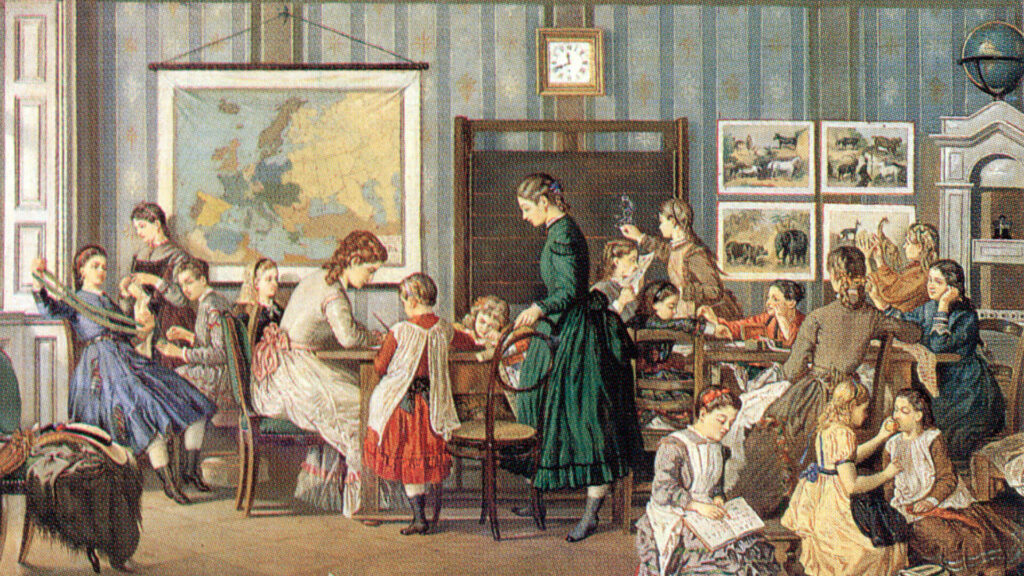

Episode 6 | Regency Schools for Girls

Charlotte Heywood’s dream of a school for girls is ultimately realized in Sanditon’s finale. While boarding schools for Regency era ladies were available, most upper- and middle-class families still supervised their daughters’ education at home. Wherever a girl was schooled, her studies usually differed from her brother’s. Girls were mainly taught “accomplishments” by their mother or a governess—domestic and social skills like needlework, dancing, drawing and music, and sometimes a language. Most upper-class ladies did learn to read and write, though that still depended on their parents’ priorities. (Charlotte thinks differently; keen eyes will notice her co-ed Sanditon School House sign reads, “Reading Writing Arithmetic Etc. by Mrs. Colbourne.”) Formal higher education was certainly not available to young women of the time and no females were accepted into university.