History in Images: Victoria Episode 4

As a cholera epidemic sweeps through the heart of London, the newly married Skerrett and Francatelli strike out on their own, and Prince Albert stands to be Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. View images and read about the real history behind the events of Victoria episode 4.

- 1.

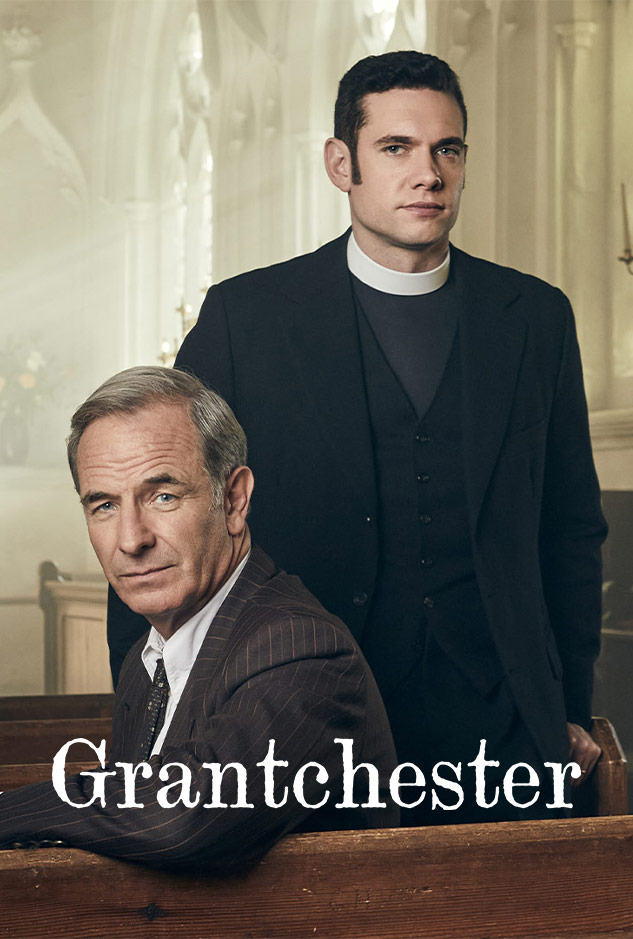

Seven Dials in London

left: A plan of the parish of St. Giles’s, 1755 | right: Seven Dials, West End of London, England, seen here in the early 19th century. From Old England: A Pictorial Museum, published 1847.

In Episode 4 , we see Skerrett and Francatelli begin their new life in the Seven Dials neighborhood of London, “The Dials” as it was known.

Today, Seven Dials is a mix of trendy shops and restaurants in the heart of London’s West End. But in the 1800s, the area was considered one of London’s greatest slums. The politician/entrepreneur, Thomas Neale, developed the land in the 1690s in such a way that the roads radiated from a central point like a star. For the center, Neale commissioned a stone pillar with sundials facing each street. The triangles of streets maximized property frontage, thus allowing for greater rental income.

Neale had hoped to attract well-to-do residents, but Seven Dials proximity to Covent Garden drew unskilled laborers and immigrants looking for cheaper lodging. Subdivisions led to overcrowding and, before long, Seven Dials came to be synonymous with poverty and crime. Yet, for those who had modest budgets, and their wits about them, the streets filled with second-hand shops and public houses were a good place to make a start. Seven Dials offered the promise of change; in fact, in the 1840s, the Chartists launched many a campaign there.

In 1835, Charles Dickens wrote about the Dials in Bell’s Life in London, asking, “Where is there such another maze of streets, courts, lanes, and alleys? Where such a pure mixture of Englishmen and Irishmen, as in this complicated part of London?… The stranger who finds himself in ‘The Dials’ for the first time, and stands Belzoni-like, at the entrance of seven obscure passages, uncertain which to take, will see enough around him to keep his curiosity and attention awake for no inconsiderable time.”

- 2.

Prince Albert’s Election Drama

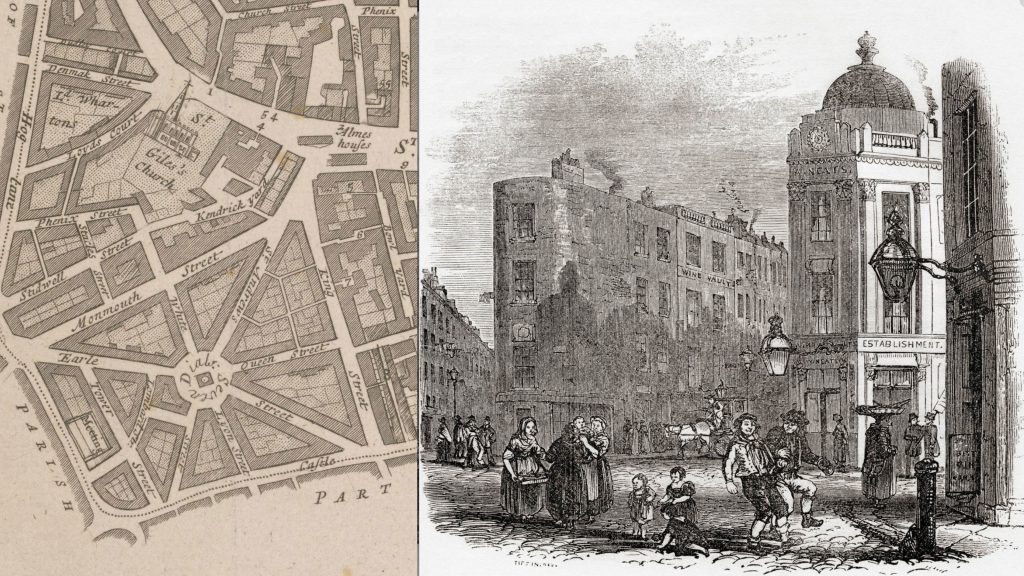

The Prince Consort c. 1849, enrobed as Chancellor of the University. Painting by Frederick Richard Say.

In episode 4, Prince Albert fights a political battle for the role of Chancellor of Cambridge University.

When the Duke of Northumberland died in 1847, Prince Albert’s interest in higher education made him a good candidate to fill the late Duke’s prestigious position as Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. Yet, while Albert secured a nomination for the role, some considered the German Prince to be highly unsuitable; he was not English-born, or Cambridge-educated, and he was only 27 years old.

Even so, it was highly unusual for the election of Chancellor to be contested, so when a group from St. John’s College nominated the Earl of Powis, it caused a bit of an uproar. Powis was a Cambridge alum from a highly-respected British family, and had further elevated his reputation by marrying into the Duke of Northumberland’s family.

Prince Albert, uneasy with the election’s newly political bent, wanted to withdraw his candidacy, but a staunch circle of supporters convinced him to remain. He ultimately won the vote, and a ceremony at Buckingham Palace on March 25, 1847, made his chancellorship official.

- 3.

The Cholera Epidemic of 1854

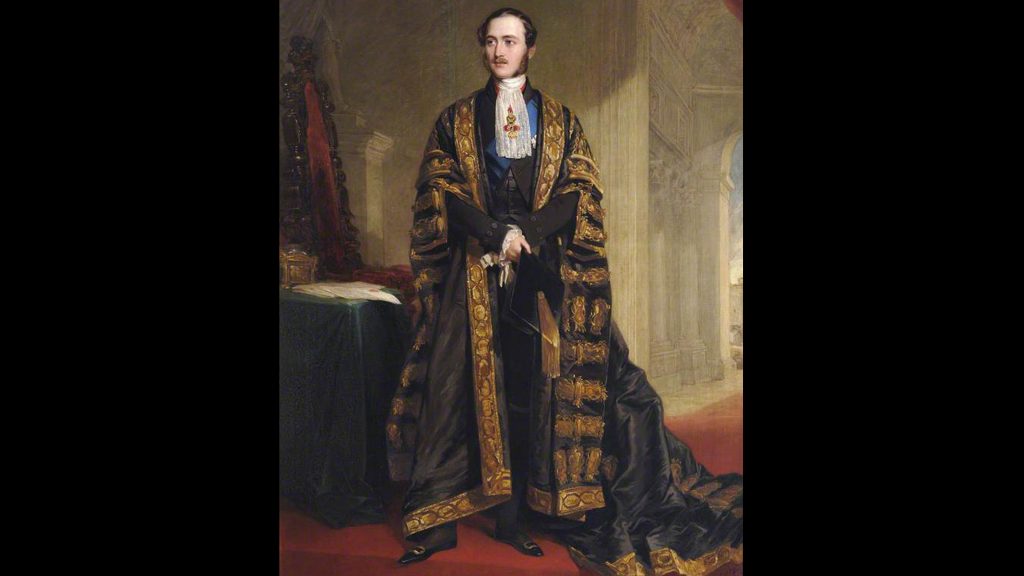

left: John Snow, 1856, right: Map of 1854 Broad Street Cholera Outbreak, Soho, London, by Dr John Snow,

A deadly cholera epidemic sweeps through a poor neighborhood in London, in Victoria episode 4, swiftly killing hundreds of residents.

In September of 1854, a few years later than depicted in Episode 4 of Victoria, a deadly cholera epidemic rampaged through the Soho district of London. At the time, popular opinion attributed the spread of disease to the Miasma Theory–“bad air” caused by rotting organic matter.. Yet a physician who lived close to the outbreak, John Snow, was not convinced.

After talking with families and studying the area, Snow pinpointed the epicenter of the outbreak, determining that within three days, 127 people had died on or around Broad Street. He observed that the houses and a school connected with these deaths were all drawing water from one particular water pump on Broad Street.

In the mid-19th century, London’s water supply system was far from sanitary. Most people pumped their water from public wells whose source was the Thames. With London’s chaotic sewage system, contamination was inevitable. Examining samples from pumps in the area, Snow identified an unknown bacterium in the Broad Street pump. After the pump was disabled, the outbreak subsided. While it took time for authorities to accept Snow’s theory, his work would eventually change the history of public health and hygiene forever.

- 4.

The Swedish Nightingale

In episode 4, members of the Palace are treated to an exquisite performance by a Swedish opera singer known as “Jenny” Lind.

Johanna Maria Lind was born out of wedlock in Stockholm, Sweden in 1820, and started her life in foster homes. She was discovered for her angelic voice at age nine, and was admitted to the Royal Theatre in Stockholm. By the time she was ten years old, she was performing for large audiences, singing her first opera in Stockholm at just 17. But Lind’s real breakthrough came in 1838 with her role as Agathe in Carl Maria von Weber’s German opera, Der Freischutz.

By the time she was 18, Lind was the Prima Donna at the Royal Opera in Stockholm, a sensation across Europe, and a favorite of Queen Victoria. In 1849, when “the Swedish Nightingale” retired from singing opera, Victoria was at the final performance.

However, Lind’s career was not over; in 1850, she was persuaded by P.T. Barnum to embark on a two-year concert tour of America. There, she was wildly popular, selling out concert halls and drawing crowds of thousands wherever she went.

- 5.

Charles Elmé Francatelli

Engraving of Francatelli drawn by Auguste Hervieu and engraved by Samuel Freeman. Frontispiece to ‘The Modern Cook’, 1845.

The hot-blooded chef Francatelli, his relationship with Nancy Skerritt and his passion for his pastries, have kept Victoria viewers enthralled. But who was the real man behind the character?

Charles Elmé Francatelli, was born in London in 1805, but grew up and trained as a chef in France. On his return to England he had a bevy of culinary posts in upscale dining clubs, even cooking for an Earl, before becoming Queen Victoria’s Maìtre d’hôtel and Chief Cook, in 1840.

Francatelli turned heads with his artistically presented and visually stunning dishes. His exquisite details took pies and jellies to new heights, and he popularized things such as ice cream in wafers (cones), and the two-course meal, (savory followed by dessert). Though only at the palace for two years, he did return to royal service in 1863, when he served as Chef de Cuisine at the house of Victoria’s oldest son Bertie. Bertie, of course, would go on to become King Edward VII.

Francatelli wrote several cookbooks, among them The Modern Cook (1845). Geared towards an upper middle-class audience, it was quite popular and ran through 12 editions. Francatelli’s A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes (1852) was distinct in that it offered practical culinary tips and recipes for those looking to economize with food.