History in Images: Victoria Episode 7

In Victoria Episode 7, Prince Albert embarks on a monumental endeavor, and trouble abroad has Lord Palmerston in hot water at home. Discover some of the real history and see historical images behind this week’s episode.

- 1.

Henry Cole, Champion of Industrial Design

left: Henry Cole | right: The world’s first commercially produced Christmas card, made by Henry Cole 1843.

In Episode 7, Albert introduces Victoria to Henry Cole, his colleague from the Royal Society of Arts. Cole has been demonstrating the revolutionary technique of electroplating.

Henry Cole was an inventor, civil servant, and a pioneer of industrial design. A student of drawing and watercolor painting, he helped with the design of the first self-adhesive postage stamp, the Penny Black, in 1840. Cole is also credited with creating the first commercial Christmas card in 1843. A true polymath, Cole also wrote a number of children’s books (under the pseudonym Felix Summerly) and designed a tea service that ended up winning a Society of Arts competition, organized by Prince Albert. Passionate about combining form with function, Cole went on to found Summerly’s Art Manufactures which supported artists who designed for commercial production.

Cole was a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. In 1847, he secured a Royal charter for the organization, and the (shortened) name was henceforth the Royal Society of Arts (RSA). It was Henry Cole who, after visiting the 1849 Paris Exhibition, realized the potential for a larger Royal Society of Arts exhibition that would include international participation. He lobbied Queen Victoria and was given the position of organizer of the Great Exhibition of 1851, advisor to the RSA president, Prince Albert.

- 2.

The Don Pacifico Affair

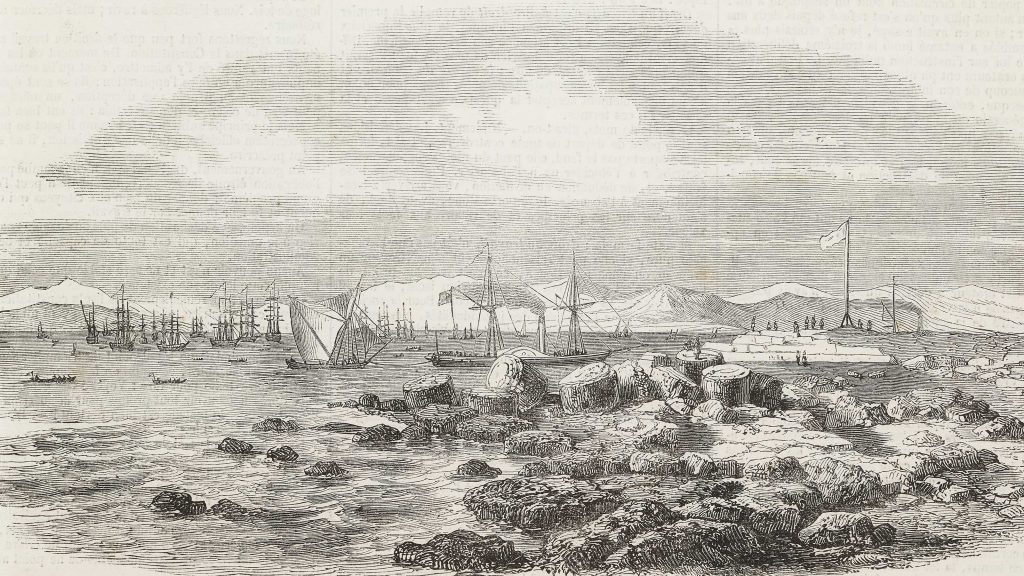

British naval fleet sets block to port of Piraeus, Greece, from Illustration, Journal Universel, No 368, Volume XV, March 16, 1850

Lord Palmerston’s handling of the Don Pacifico Affair comes under great scrutiny in Episode 7, not only from the British public, but from Buckingham Palace as well!

Don Pacifico was a Jewish merchant of Portuguese descent living in Athens. His reputation was somewhat tarnished in 1842 when he was dismissed from a position as consul-general to Greece after abuses of power were brought to light.

During Easter 1847, the Jewish financier Amschel Mayer De Rothschild was in Athens. To be respectful of his visit, the Greek government outlawed a rather anti-Semitic Greek Easter tradition involving the burning of effigies of Judas Iscariot. This political maneuver was not popular with locals, and a riot ensured. A mob ransacked and looted the home of Don Pacifico, beating him and his family. The police looked the other way, and when the Greek government refused to make reparations, Don Pacifico appealed for help from Great Britain. Having been born in Gibraltar, he could claim British nationality.

The case dragged on, but in 1850, Lord Palmerston took action, sending a British naval blockade to seize Greek ships and property in the amount of Pacifico’s claims. The blockade lasted two months and caused a rift with France and Russia, who shared a protectorate of Greece and did not support Britain’s intervention. Queen Victoria herself was highly critical of Palmerston dispatching 14 British ships, 731 guns and 8,000 sailors, all for the sake of one “foreigner.”

In an almost five-hour speech to Parliament, Palmerston defended his actions, famously declaring, “As the Roman in days of old, held himself free from indignity, when he could say, ‘Civis Romanus sum’, so also a British subject, in whatever land he may be, shall feel confident that the watchful eye and the strong arm of England will protect him from injustice and wrong.”

The Greeks ultimately agreed to pay reparations and Palmerston’s “gunboat diplomacy,” as it came to be known, was seen as a victory in foreign policy, as well as being a boost to the foreign secretary’s soaring popularity.

- 3.

Joseph Paxton and the Amazonian Lily

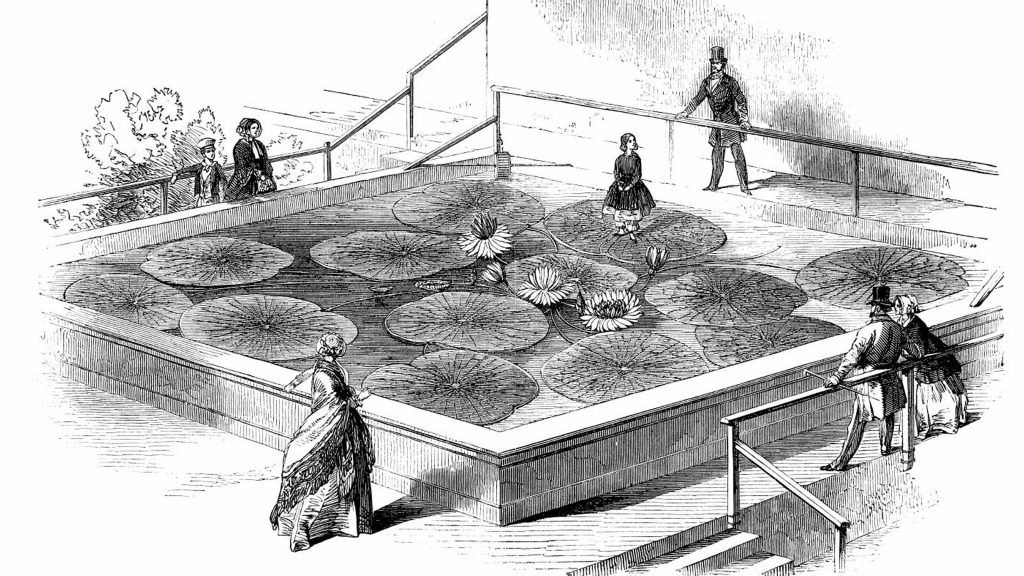

Paxton’s nine-year-old daughter Annie stands atop the gigantic water-lily (Victoria Regia), in flower at Chatsworth. Illustration from The Illustrated London News, Nov 17, 1849.

As president of the Royal Society of Arts, Prince Albert wanted to create a Great Exhibition the likes of which had not been seen before, showcasing art and industry from all over the world. The problem was how to house something of this scale.

Enter Joseph Paxton, chief landscaper for the Duke of Devonshire at the gardens of Chatsworth. The Duke was in possession of a giant Amazonian lily (Victoria regia), which had been transported all the way from British Guiana. It was surviving but hardly thriving at Kew Gardens. Paxton took a seedling from the plant and, under his attentions, the lily grew as it did in its native habitat, to colossal dimensions. The first flower measured a yard in circumference.

Studying the underside of the lily-pads, Paxton saw that the web-like structure of the lily’s veins provided the leaf with substantial buoyancy and structure, so much so that a human could balance on a pad without it submerging. Calling it a natural feat of engineering, he designed and built a light and airy greenhouse for the lilies, modeled on the ridge and furrow configuration of the lily’s pads.

- 4.

Bloomers!

left: Amelia Bloomer as depicted in the April 1851 edition of The Lily | right: A girl wearing bloomers is the center of attention, date: 1854

Queen Victoria, distressed by Lord Palmerston’s rogue decree to send a naval blockade to Greece, summons the foreign secretary to the Palace. He jokes with her that she has sent for him to discuss the curious “bloomer” craze taking over America.

In the mid-1800s, women wore floor-length, corseted dresses with half-a-dozen petticoats that could weigh up to 15 pounds; were impractical and constricting; and sometimes made the simple act of breathing a challenge. The idea that current women’s fashions were cumbersome, unnecessary, and even hazardous to women’s health, was not a new one. Doctors had expressed concern about the health of pregnant women in such restrictive clothes, and more liberal or health-conscious newspapers had circulated articles protesting women’s fashions.

In July 1848, a native of upstate New York, Amelia Bloomer, attended a convention in Seneca Falls, organized by prominent women’s rights activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Inspired, Bloomer founded, in 1849, a bi-weekly newspaper called The Lily. Initially dedicated to women’s suffrage, The Lily was soon promoting women’s causes in general, and in an April, 1851 article, Bloomer recommended that women switch to “Turkish trousers” or pantaloons, an outfit that involved loose fitting pants with a knee-length skirt. Accompanying the article was a picture of Bloomer herself, wearing pantaloons.

Though they were not her invention–others had already suggested and sported the fashion while she merely advocated for it–pantaloons became a craze that soon made its way to London, where they were quickly dubbed “bloomers”. The outfit caused a storm of controversy; in fact, women’s rights advocates eventually returned to more conservative apparel in fear that the bloomer hullabaloo was pulling focus from more important feminist causes.

- 5.

Archery in the Victorian Era

Queen Victoria(1819-1901), pictured here when a young Queen, trying her hand at archery

During Episode 7, Queen Victoria is seen in the palace gardens, honing her archery skills alongside her sister Feodora.

Queen Victoria took up archery as a young women and continued to practice for many years. As a young princess, she had been a patron of the Society of Leonards Archers. On her accession to the throne, Victoria changed the name to Queens Royal St Leonards Archers. It was an elite club, a who’s who of the aristocracy, with members being elected by ballot, and lavish prizes for tournament winners.

Significantly, many of St Leonards members were women; indeed, most archery clubs had a healthy female presence. Archery was one of the few sports in which ladies could compete in the 1800s. Victorians considered it a dignified and graceful way for women to exercise, and indeed it took some muscle to operate the bow, which could weigh anywhere from 40-60 pounds.

Bows made from the yew tree were thought to be superior in strength and elasticity, and hemp was used for the strings. An archer’s kit contained arrows made from a mix of ash and pine, and a quiver composed of tin or leather. An acorn-shaped cup held a blend of mutton fat and tallow to help grease the shooting glove, enabling it to slide more easily off the bowstring. Targets had circles of gold, red, blue, black and white, worth nine, seven, five, three, and one point(s), respectively.