History in Images: Victoria Episode 8

The Great Exhibition is finally here! Prince Albert fears that it won’t live up to expectations, but Victoria is determined to support her husband’s big moment. Palmerston makes another rogue political move, and this time does not emerge unscathed. And some royal match-making is underway. See historical images from the episode’s events, and find out about some of the real history behind the Victoria Season 3 finale.

- 1.

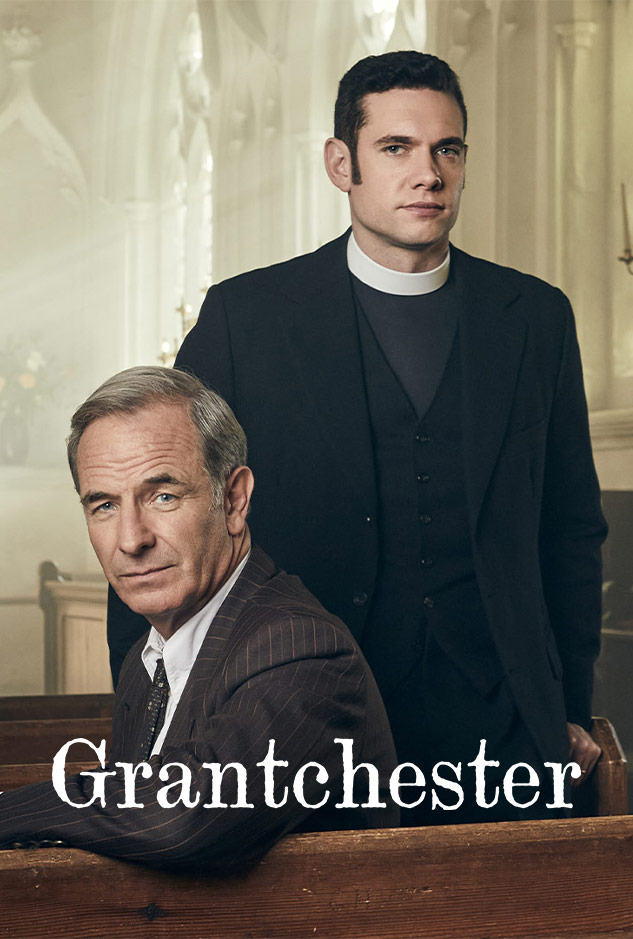

Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace during the Great Exhibition, London, 1851

Work on Crystal Palace began on August 1, 1850 and, defying skeptics, Joseph Paxton completed the magnificent structure just in time for May 1, 1851, the opening of the Great Exhibition—exactly nine months after he submitted his plans.

Dubbed the eighth wonder of the world, the Crystal Palace was vast, covering 19 acres of London’s Hyde Park–more than five football fields. It was built with a cast-iron frame supporting many thousands of sheets of plate glass, more glass than had ever been seen in one building. Paxton drew upon his experience designing greenhouses for the Duke of Devonshire, also teaming up with structural engineer Charles Fox and an overseeing committee that included the famous British mechanical engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

An engraving of the Transept of the Great ExhibitionInside the structure, were fountains with jets that rose high into the air. Hyde Park’s trees were incorporated within the structure, further emphasizing the size of the building. The ground floor galleries included more than eight miles of tables, showcasing stunning displays of technology and craft from around the world. Over 14,000 exhibitors participated, from more than two dozen countries. It was the first ever theme park, with plenty to entertain, including a prehistoric swamp complete with the earliest prehistoric models of dinosaurs ever built.

The exhibition lasted six months and attracted six million visitors, including celebrities like Charles Darwin, Charlotte Bronte, George Eliot, Charles Dickens, and Lewis Carroll. Profits from the Exhibition were used to found the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum and the Natural History Museum, and Paxton and Fox were knighted for their contributions.

- 2.

The Great Exhibition of 1851

The interior of the Crystal Palace in London during the Great Exhibition of 1851.

As Victoria wanders among the displays at the 1851 Great Exhibition, she stops to marvel at a penknife with 83 blades. Such a knife actually was crafted especially for the Great Exhibition, sporting 1,851 blades in honor of the year.

The sheer number of marvels on display at the Exhibition was beyond comprehension. New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley, one of many Americans who crossed the Atlantic to visit the Great Exhibition, lamented, in a dispatch back to the States, that after spending five full days meandering through the halls of the Exhibition, he hadn’t come close to seeing all he wanted to see.

To the Victorian public, the exhibits were awe-inspiring. A “Machines in Motion” hall mesmerized visitors with complicated devices, turning raw cotton into cloth, or spinning silk into fabric before their eyes, like magic. There was a great hall devoted to agricultural innovations like steam-powered tractors, machines to grind grain, and plows made of cast-iron. Queen Victoria wrote in her journal, “What used to be done by hand and take months doing is now accomplished in a few instants by the most beautiful machinery. We saw hydraulic machines, pumps, filtering machines of all kinds, machines for purifying sugar—in fact every conceivable invention.”

Clockwise from top left: A taxidermy tableaux by Hermann Ploucquet, The Kittens at Tea — Miss Paulina Singing, 1851 | Lane’s telescopic view, of the ceremony of Her Majesty opening the Great Exhibition of All Nations | Visitors at the fur exhibition at the Great Exhibition, from The Illustrated London News, 1851

On the second floor, visitors could admire displays of musical instruments, including folding pianos, as well as revolutionary medical gadgets and philosophical curiosities. A “Tempest Prognosticator” devised by George Merryweather used leeches to predict impending storms, while physicist Frederick Collier Bakewell demonstrated his precursor to the fax machine. Queen Victoria’s Koh-i-Noor diamond had a choice spot in the central gallery, and was a hugely popular attraction, partly due to its size and its £1-2 million pricetag. Cyrus McCormick’s celebrated reaper was on show, as were revolvers by Samuel Colt, state-of-the-art astronomical telescopes, a room of furs sent from Canada, carved ivory from India, velocipedes (early versions of the bicycle), and a full-size stuffed elephant with magnificent regal trimmings, straight from the Raj (British India). Taxidermy was a bit of a craze at the time, and no less than 14 taxidermists showcased their work at the Great Exhibition. Herman Ploucquet’s displays of anthropomorphic taxidermy drew especially large crowds. The exhibition space also featured the first modern pay toilets, which cost a penny to use and led to the phrase “spending a penny,” meaning using the bathroom.

On leaving the Exhibition, visitors could purchase souvenirs such as Lane’s Stereoscopic Views, which gave a miniature panorama of the Great Exhibition, accessible via a peep hole.

- 3.

The French Coup D’État of 1851

French troops on the streets of Paris, France during Prince Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état of 1851. From Historia de los Crimenes del Despotismo, published 1870.

Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte) had been elected President of France in 1848 and, under the French constitution, could not be re-elected for a second term. With his tenure nearing an end, Louis-Napoleon made a valiant but ultimately unsuccessful effort to reform the provisions of the constitution so that he could remain in power. Defeat did not sit well with him, and on December 2, 1851, Louis-Napoleon staged a carefully planned coup d’état in Paris, installing himself as Emperor of France, a position he retained until 1870.

Louis-Napoleon’s success, however, was to bring about the end of Lord Palmerston’s career as British foreign secretary. On Dec 16, Palmerston wrote to the British representative in France, Lord Normanby, expressing his congratulations and support for Napoleon’s actions. He did this without approval from either Prime Minister Lord Russell or the Queen, neither of whom were in support of the coup. Palmerston argued that Napoleon’s presidency was in Britain’s best interest, but he had stepped too far out of line, and demands for his resignation were swiftly forthcoming. Palmerston stepped down in December, 1851.

- 4.

Royal Match-Making

left: Princess Royal (future German Empress), c. 1855 | right: Vicki & Friedrich, the Crown Princess and Crown Prince of Prussia in 1858

In Victoria Episode 8, Princess Vicky is introduced to His Majesty the King of Prussia and his son Fritz, the Crown prince.

In 1851, Victoria and Albert invited their close allies Prince William of Prussia and his wife Princess Augusta of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach to visit the Great Exhibition. The Prussian monarch brought along his two children, Friedrich (Fritz) and Louise. Princess Vicky was only ten years old, but Prince Albert and Queen Victoria were already thinking about a match for her that would preserve the family ties to Germany.

Friedrich was ten years older than Vicky, but was impressed by her intelligence, maturity, and fluency with the German language. The two struck up a correspondence after the visit, and “Fritz” visited the British royal family again, in 1855, this time at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. Three days into his visit, he asked Victoria for her daughter’s hand in marriage. Victoria and Albert were delighted and gave consent with one condition: The 15-year-old Vicki had to wait until she turned 17 to get married.