|

|

Accidental Discoveries

by Lexi Krock

Accidents in medicine: The idea sends chills down your spine as you conjure up

thoughts of misdiagnoses, mistakenly prescribed drugs, and wrongly amputated

limbs. Yet while accidents in the examining room or on the operating table can

be regrettable, even tragic, those that occur in the laboratory can sometimes

lead to spectacular advances, life-saving treatments, and Nobel Prizes.

A seemingly insignificant finding by one researcher leads to a breakthrough

discovery by another; a physician methodically pursuing the answer to a medical

conundrum over many years suddenly has a "Eureka" moment; a scientist who

chooses to study a contaminant in his culture rather than tossing it out

stumbles upon something entirely new. Here we examine seven of medical

history's most fortuitous couplings of great minds and great luck.

|  A laborer scrapes the bark from a cinchona tree. The

bark is then sundried and pulverized to make the drug quinine.

A laborer scrapes the bark from a cinchona tree. The

bark is then sundried and pulverized to make the drug quinine.

|

Quinine

The story behind the chance discovery of the anti-malarial drug quinine may be

more legend than fact, but it is nevertheless a story worthy of note. The

account that has gained the most currency credits a South American Indian with

being the first to find a medical application for quinine. According to legend,

the man unwittingly ingested quinine while suffering a malarial fever in a

jungle high in the Andes. Needing desperately to quench his thirst, he drank

his fill from a small, bitter-tasting pool of water. Nearby stood one or more

varieties of cinchona, which grows from Colombia to Bolivia on humid slopes

above 5,000 feet. The bark of the cinchona, which the indigenous people knew as

quina-quina, was thought to be poisonous. But when this man's fever

miraculously abated, he brought news of the medicinal tree back to his tribe,

which began to use its bark to treat malaria.

Since the first officially noted use of quinine to fight malaria occurred in a

community of Jesuit missionaries in Lima, Peru in 1630, historians have

surmised that Indian tribes taught the missionaries how to extract the chemical

quinine from cinchona bark. In any case, the Jesuits' use of quinine as a

malaria medication was the first documented use of a chemical compound to

successfully treat an infectious disease. To this day, quinine-based

anti-malarials are widely used as effective treatments against the growth and

reproduction of malarial parasites in humans.

A depiction of Edward Jenner vaccinating James

Phipps, a boy of eight, on May 14, 1796.

A depiction of Edward Jenner vaccinating James

Phipps, a boy of eight, on May 14, 1796.

|

|

Smallpox vaccination

In 1796, Edward Jenner, a British scientist and surgeon, had a brainstorm that

ultimately led to the development of the first vaccine. A young milkmaid had

told him how people who contracted cowpox, a harmless disease easily picked

up during contact with cows, never got smallpox, a deadly scourge.

With this in mind, Jenner took samples from the open cowpox sores on the hands

of a young dairymaid named Sarah Nelmes and inoculated eight-year-old James

Phipps with pus he extracted from Nelmes' sores. (Experimenting on a child

would be anathema today, but this was the 18th century.) The boy

developed a slight fever and a few lesions but remained for the most part

unscathed. A few months later, Jenner gave the boy another injection, this one

containing smallpox. James failed to develop the disease, and the idea behind

the modern vaccine was born.

Though doctors and scientists would not begin to understand the biological

basis of immunity for at least 50 years after Jenner's first inoculation, the

technique of vaccinating against smallpox using the human strain of cowpox soon

became a common and effective practice worldwide.

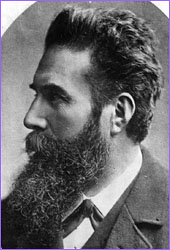

|  Physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845-1923),

discoverer of the X-ray.

Physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845-1923),

discoverer of the X-ray.

|

X-Rays

X-rays have become an important tool for medical diagnoses, but their discovery

in 1895 by the German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had little to do

with medical experimentation. Röntgen was studying cathode rays, the

phosphorescent stream of electrons used today in everything from televisions to

fluorescent light bulbs. One earlier scientist had found that cathode rays can

penetrate thin pieces of metal, while another showed that these rays could

light up a fluorescent screen placed an inch or two away from a thin aluminum

"window" in the glass tube.

Röntgen wanted to determine if he could see cathode rays escaping from a

glass tube completely covered with black cardboard. While performing this

experiment, Röntgen noticed that a glow appeared in his darkened

laboratory several feet away from his cardboard-covered glass tube. At first he

thought a tear in the paper sheathing was allowing light from the high-voltage

coil inside the cathode-ray tube to escape. But he soon realized he had

happened upon something entirely different. Rays of light were passing right

through the thick paper and appearing on a fluorescent screen over a yard away.

Röntgen found that this new ray, which had many characteristics different

from the cathode ray he had been studying, could penetrate solids and even

record the image of a human skeleton on a photographic negative. In 1901, the

first year of the Nobel Prize, Röntgen won for his accidental discovery of

what he called the "X-ray," which physicians worldwide soon adopted as a

standard medical tool.

Continue: Allergy

Dr. Folkman Speaks |

Cancer Caught on Video

Designing Clinical Trials |

Accidental Discoveries |

How Cancer Grows

Help/Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Cancer Warrior Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated February 2001

|

|

|