|

|

|  Dr. Judah Folkman

Dr. Judah Folkman

|

Dr. Folkman Speaks

In 1961, while conducting medical research in a U.S. Navy lab, Dr. Judah

Folkman stumbled upon a hidden secret about how cancer grows. Before the decade

was out, he was forming the theory that would occupy the rest of his

professional life. He called that theory angiogenesis, and in it he postulated

that tumors could not grow larger than the head of a pin without a blood

supply. He also believed that the tumor secreted some mystery factor that

stimulated new blood vessels to form, bringing nutrition to the tumor and

allowing it to grow.

But Dr. Folkman went even further: He also proposed that if the new

blood-vessel growth to the tumor could be blocked, that might offer an entirely

new way to treat cancer. After decades of work, Dr. Folkman and his team are now

watching as clinical trials begin with two recently discovered angiogenesis

inhibitors, endostatin and angiostatin. In this interview, drawn from those conducted for "Cancer

Warrior" by NOVA producer Nancy Linde, hear Dr. Folkman talk about his team's

ground-breaking discoveries and his hopes and fears for the new therapy.

NOVA: What was your first "Eureka" moment with angiogenesis?

Dr. Folkman: The first one was in the 1960s when we saw that in the isolated

organs growing in the glass chambers in the Navy that the tumors implanted

there all stopped at the same size. There should have been a bell-shaped curve

like in all biology, but all the same size meant that something was stopping

them. It took a few years to figure out it was the absence of blood vessels. I

had a feeling this is really something important. I didn't have any idea that

it would be some 30 years to try to understand the process by which tumors are

able to recruit their own private blood supply and just keep going.

NOVA: Such moments must be worth everything, especially since they're so few

and far between.

Dr. Folkman: Most research is failure. You go years and years and years, and

then every once in a while there is a tremendous finding, and you realize for

the first time in your life that you know something that hour or that day that

nobody else in history has ever known, and you can understand something of how

nature works.

NOVA: When did you first lay out your theory?

Dr. Folkman: A 1971 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine

presented the idea in a much larger form. One, that the blood vessels in a

tumor were new, and the tumor had to recruit them. Two, that it recruited the

vessels by sending out some factor, which we called TAF, tumor angiogenesis

factor, because we didn't know what it was that was diffusible. (Diffusion

means like if you put some ink on a table cloth, it travels, but not a long

distance.) Thirdly, we put forward the idea that these diffusible proteins

would bring in the vessels. And fourthly, that if you could turn this process

off the tumors should stay as small as they had in the thyroid gland and in the

lining of the abdomen that I had seen in surgery, where they are all the same

size and tiny but without blood vessels.

NOVA: Did you ever fear you were jumping the gun, since much of the verifying

research had yet to be done?

Dr. Folkman: I remember in some early grants I wrote that I outlined what I

thought would be the whole future—there would be possible inhibitors and

stimulators [of angiogenesis], and there would be pure proteins. You never these

days lay all that out in a grant; you focus it. Well, I got cold feet and

thought, Oh I'm giving away too much.

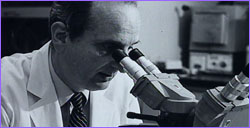

|  Judah Folkman and his team had to conduct hundreds of experiments

before the scientific community began to accept their unconventional

ideas.

Judah Folkman and his team had to conduct hundreds of experiments

before the scientific community began to accept their unconventional

ideas.

|

Now, Dr. John Ender's lab was right next to mine. He had won the Nobel Prize

for the polio virus and was a very great scholarly gentleman. I showed him this

grant and said I'm worried that I'm giving away too much. He read it right

there. I remember him taking out his pipe, and he said "It is theft-proof.

You'll be able to work at your own pace I figure for 10 years before anybody is

going to believe this." He thought maybe these ideas were right but that I'd

never be able to convince anybody without dozens of experiments. It turned out

that hundreds of experiments were necessary over many years.

NOVA: Especially because you were a surgeon and not a researcher?

Dr. Folkman: Surgery has the disadvantage that the training takes so long and

is so physically demanding. It's like training for the Olympics practically.

There's often little time for any kind of research or scholarly work, and

surgeons often do not have any ability to have the very long period of

scientific training that basic scientists have. And so surgeons often are

ridiculed because they are thought not to be able to do research. Yet many

great, interesting, and important advances have come from surgeons.

NOVA: Which is harder in your experience, being a doctor or being a

researcher?

Dr. Folkman: Clinical medicine has tremendous feedback, so the people who work

in it are willing to work night and day. Patients just call you up all the time

and say you saved my son's life and all that. Research is the opposite. It's

just years of frustration. You have to live with experiments that don't work

and grants that don't get funded. You have nothing to show for it. You've got

critics all over, and scientists are sometimes mean to each other; they

criticize the ideas in the name of scientific skepticism. It's not an easy

life. You know that line, "I've been rich, and I've been poor, and rich is

better"? Well, it's easier to be a physician than to be a researcher. I've been

both, and physician is easier.

Judah Folkman: "I kept saying the ideas, I

think, are right, and it will just take a long time for people to see

them."

Judah Folkman: "I kept saying the ideas, I

think, are right, and it will just take a long time for people to see

them."

|

|

NOVA: What gave you the confidence to go on?

Dr. Folkman: Well, I always thought of it in an amused way, because I knew

something that no one else knew, and I had been at the operating table. It

wasn't the surgeons who were criticizing, it was basic scientists, and I knew

that many of them had never seen cancer except in a dish. I knew that they had

not experienced what I had experienced. The idea of tumors growing in three

dimensions and needing blood vessels in the eye, in the peritoneal cavity, in

the thyroid, and many other places, and the whole concept of in situ cancers

and tumors waiting dormant—I had seen all that. So I kept saying the ideas,

I think, are right, and it will just take a long time for people to see

them.

NOVA: So when did perception of your work start to change among

researchers?

Dr. Folkman: By about the end of the `70s people began to say, Okay, they are

new vessels, we agree. But it's a side effect of dying tumor cells. It's like

pus in a wound. When Robert Auerbach came [to our lab] as a sabbatical

professor, that was the conventional thinking. But he did the experiment that

disproved that as a single, crystal-clear paper. He put live tumor cells in one

eye of a rabbit, and he put dying tumor cells in the other, and no blood

vessels came to those, only to the live ones. He said they must be live in

order to recruit the private blood supply. That single paper changed a lot of

people's thinking.

I would say the watershed year for complete change of thinking amongst

scientists was about 1989. By then there were such strong experiments coming

from our lab, from Genentec's lab, and from Europe that tumors not only induced

new vessels but were angiogenesis-dependent, that most scientists began to

accept that. But it took a long time.

NOVA: In 1984, your team published a paper in Science about the

discovery of the first angiogenic factor the year before. That must have

stirred things up.

|  Watch clip of Judah Folkman on "persistence

and obstinancy."

Watch clip of Judah Folkman on "persistence

and obstinancy."

QuickTime

RealVideo: 56K |

ISDN+

|

Dr. Folkman: That paper had great transforming power. Almost overnight many,

many, many critics were transformed into competitors, because people began to see

that there was a molecule in this field. That was the first; there are now

17.

I was beginning to wonder whether there would ever been an angiogenic factor.

We had spent so many years on it. In general, if you don't find something in

four or five years, people say it's not there. In research, there's a very fine

line between persistence and obstinacy. You do not know whether if you're

persistent a little while longer you'll make it, or whether you're just being

obstinate, [and it] doesn't exist. And, of course, you can keep on going, stay

with an idea too long—[that's] called pigheadedness. I was beginning to

think we had crossed that line and were spending money and had nothing to show

for it.

When that came that was a great sense of relief, that it actually did exist.

It's like Sputnik. The U.S. had all the information to put up a satellite, but

we didn't until Russia did. Then suddenly we said, Oh you can do it. Once

people saw that it was possible [to find angiogenic factors], they began to

look and found other ones.

Continue: Finding angiogenesis inhibitors

Dr. Folkman Speaks |

Cancer Caught on Video

Designing Clinical Trials |

Accidental Discoveries |

How Cancer Grows

Help/Resources |

Transcript |

Site Map |

Cancer Warrior Home

Editor's Picks |

Previous Sites |

Join Us/E-mail |

TV/Web Schedule

About NOVA |

Teachers |

Site Map |

Shop |

Jobs |

Search |

To print

PBS Online |

NOVA Online |

WGBH

© | Updated February 2001

|

|

|